Editors note: Guardian correspondent John Ross is traveling across the nation pomoting his new book, El Monstruo — Dread & Redemption in Mexico City, and is sending us dispatches from the road. This week: Twin Cities, Madison and Northern Michigan.

1. BLUE IGLOO

As I deplaned the Southwest Shuttle from Denver wrapped in my blue igloo, a puffed up garment that doubles my skeletal girth, a sudden spasm of panic punched me in the gut. Had I slept through my stop and disembarked in Fargo, North Dakota instead?

Minneapolis might just as well have been Fargo. The dead winter landscape lay frozen under week-old snowdrifts and the Twin Cities shivered in negative wind chill numbers beneath a leaden sky from which a cold hard rain would pelt down for a week. Fargo or Minneapolis? It didn’t much matter where I had landed – just don’t toss me into the wood chipper.

On my first evening in this desolate region, I was invited to dialogue with the Minnesota Immigrant Freedom Network at a community center in St. Paul. About 15 transplanted Mexicans, many of them related by marriage or friendship, pulled together in a circle in the gymnasium while the kids romped in the other room. Each called out his or hers’ “patria chica,” their home state or region or town. I talked about Mexico down on the ground today in the cheerless winter of 2010, the 100th anniversary of a distant revolution. How four out of every ten heads of households are out of work. 10,000 farmers and their families forced to abandon their milpas as millions of tons of NAFTA corn inundate the country. 19,000 dead in Felipe Calderon’s disastrous attempt to beat down the drug cartels. Who will be next?

Those in the circle leaned forward on their folding chairs, bending into my words as if I was a messenger bringing bad news from home. One woman began to weep and another rose to comfort her.

Later, I pulled out my book, El Monstruo – Dread & Redemption in Mexico City to show them what I had written. Families who would probably not eat meat for a week if they bought one snapped up three Monsters and asked me to sign them for their children — Alejandra, Yesica, Jeni, Alfonso, Jonaton — so that they could learn about the country they had been forced to abandon, in their new language.

As the session wound down, Mariano (not his real name) invited the families to a Jewish Seder the next week at a progressive Minneapolis schul. Then they would get on the buses and head for Washington D.C., a 150 hour round trip, to march for immigration reform on March 21st, the first day of spring. In the nooks and crannies of Obama’s America, Mexicans were beginning to come out of four years of social hibernation to rally for immigration reform, not a hot button issue in this economically strewn landscape.

I hung up with my old camarada Tomas Johnson, one of the apostles of fair trade Zapatista coffee — similar dispensaries like Just Coffee in Madison and Higher Grounds in Michigan are sprinkled over the frigid Midwest. Café has played a diminished role in the slender Zapatista economy ever since Muk’Vitz, a Tzotzil Indian cooperative, imploded when coffee prices soared — coyotes, bottom-feeder speculators, started showing up on the members’ doorsteps offering a few pesos more than the fair trade price.

Coffee is not an ideal resource upon which to build Zapatista autonomy — the price is set far away on commodity exchanges in London and New York and the product itself is destined for the jaded palettes of the connoisseur class in the cities of the north. Moreover, the coffee crop soaks up corn land and adds nothing to indigenous nutrition.

I marked my journey into my 73rd year at a house fiesta hosted by Tomas’s steady squeeze, an audiologist who gifted me with a hearing aid so that I might be able to decipher that questions hurled at me from the small audiences I address. This time last year, I was being wheeled into a green, antiseptic operating room for a round of chemotherapy that would k.o. the tumor that had taken over my liver. This birthday is the real gift.

I entertained privileged white students at several universities during my stay in the Twin Cities, got hopelessly lost in a frigid wasteland trying to find a Lutheran college, told tall tales to a handful of Raza at the U. of Minn, and attended a showing of the Benny More bio-pic at a jam-packed local theater. Benny’s scintillating calor radiating from the screen in waves of tropical heat juxtaposed oddly against the backdrop of the frozen north. Minneapolis-St Paul, with their new populations of color – Somalis, Ethiopians, Eritreans, Hmung, and Latinos – spice up this staid old state with exotic flavors. The music has changed: Reggaeton and Rancheros have replaced Spider John Koerner. I drink in the Albert Ayler-like contortions of a longhaired white boy at a jam session downstairs at the Clown Lounge.

Politics too are not as usual in this once-upon-a-time farmer-labor socialist paradise: Keith Ellison is the nation’s first Muslim congress person and a middle-of-the-road Democrat comedian stands small in the shoes of Paul Wellstone. In the other corner, the pit viper Michelle Bachman spits her venom into the black lagoons of Obamalandia.

II. TURKEY MOLE

I’m back on the Big Dog — there are plenty of Mexicans here but no Mexican bus. On the jump over to Madison, I chat with a well-seasoned black man during a smoke break. He wants to know where I’m headed. I’m on a low-rent book tour, I explain, I move from city to city to sell my books. “I’m on a book tour myself,” he laughs, “I get off where I want to and see if I like it or not. Hung up in Oswego for eight days but wasn’t anything there for me…”

There is a down-at-the-heels traveling class — the evicted and foreclosed, laid off and uprooted — rolling around the underbelly of this damaged country with no fixed destination in mind, looking for a place to light, some place that feels like home.

Norm Stockwell, who keeps WORT-FM, the Voice of Madison’s Voiceless, choogling, picks me up at the Greyhound depot, a furniture-less warehouse that resembles an immigrant detention center on the outskirts of town, and drives me over to the once-a-month Socialist pot-luck, but only scraps and few stained paper plates are left. A few hours earlier, the Madison P.D. visited the premises at the behest of the Wisconsin Socialist Party to remove a truculent member who had been abruptly expelled from its ranks, an astonishingly unpolitical resolution to a political dispute.

Madison is a city that doesn’t leave much up to chance. Cops are ever at the ready to surveil radical meetings. One cannot post a hand-scrawled street sign protesting injustice without first obtaining a permit from the city. No household is allowed to house more than three chickens (no roosters), a law that necessitates chicken inspectors and has given birth to the Chicken Liberation Front.

The State Capitol, a knock-off the Nation’s, is forever on the eyeline in Madison to remind one of the power of the State, I expect. The city is laid out on a grid so that all avenues spoke off from its monstrous dome – you have to move out of town to escape the radiation.

On Saturday, March 20th, a fistful of eternal protestors gathered at the foot of this granite beast to mark the start of the eighth year of the illegal invasion and occupation of Iraq and the decimation of millions of its people. As I trudged up State Street towards the Capitol, I flashed back to our feverish days as Human Shields in Baghdad in March 2003 and thought about Sasha for whom the war never goes home, climbing the hills of Amman, delivering collateral repair from dawn to dusk to the million Iraqi refugees that forgotten war has exiled to the Jordanian capitol.

Our presidents invade so many foreign countries that they can’t even remember the name of the last one they destroyed. Iraq has been erased from the North American mind screen in favor of Afghanistan, the Good War on Obama’s agenda. Last month, Sasha and Mary’s Collateral Repair Project took in just $50 in donations and CRP is in danger of folding. Send them some Yanqui shekels at (www.collateralrepairproject.org.)

The annual commemoration of the Iraqi genocide draws smaller and smaller knots of humanity each year — 80 or so souls in Madison, 500 in San Francisco, not 10,000 in Washington. But the next day, as Baracko’s Dems braved the racist jibes and hard fruit of the Teabaggers to enter the hallowed halls of Congress and narrowly vote up a phony health care reform bill that excludes immigrants from coverage and leaves the insurance congloms on top, 200,000 assembled outside to back up a proposed immigration reform that smells just as cheesy as Obamacare.

The rally proved to be the largest confluence of immigrant workers since that miraculous May 1st four years ago when millions came out of the shadows to shout “aqui estamos y no nos vamos.” After that milestone moment, the immigrant rights movement was driven into the underground by Bush’s ICE raids, Lou Dobbs, the Minutemen, real-time Mexico bashing with knives and bottles, Sheriff Joe’s Arizona storm troopers, good ol’ American-as-apple-pie racism, and the squeamish response of the official Latino leadership.

Now the indocumentados are taking their first baby steps back into the maelstrom of U.S. politics. Hundreds of grassroots groups like the Minnesota Immigration Freedom Network rented buses and drove off to Washington on the first day of spring and May 1st, the day on which immigrant workers first took to the streets of America 124 years ago in the battle for the eight hour day, now looms large on the calendar of resistance.

Lester Dore is a graphic artist who operates under the influence of the king of the calaveras Jose Guadalupe Posada, the brothers Flores Magon, and the breathtaking explosion of popular art that detonated on the walls of Oaxaca during the 2006 uprising in that southern city. Lester whips up a pair of prints to celebrate the publication of “El Monstruo” and the life after death of Praxides G. Guerrero, the first anarchist to fall in the 100 year-old-this-year Mexican revolution. He serves up a big pot of Mole de Guajalote (Turkey) and invites us over. Three compas from Toluca in Mexico State share the sumptuous repast and the conversation quickly slides into Mexican. I learn the origin of the Chilango-ismo “teparocha” (falling down drunk) but eschew the vino (the liver lives on.)

III. SANCTUARY IN THE HEARTLAND

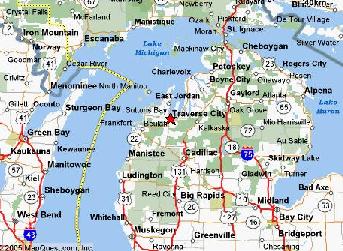

Driving the long route around Lake Superior into northern Michigan, the first tentative fingers of spring have brought a thawing to the land. The cherries that draw thousands of migrant workers to the Lower Peninsula are threatening to burst into bud. Gladys Munoz (her real name) directs Migrant Health Services for seven northern Michigan counties. She is based in Traverse City, a comfortable upper crust enclave — the billion buck mansions out on the peninsula are in the El Chapo Guzman category of ostentation (Michael Moore is rumored to be in residence in the environs ensconced in a lavish log cabin roughly the size of downtown Flint.)

Gladys knows where the bodies are buried. We ply the backroads to the labor camps hidden away down in the dank gullies. Guatemalans and Mexicans stream into this region each spring to do the stoop labor no gringo will do and pick the Maraschinos that top off the parfaits of the few upwardly mobile Americans left in the wake of the ravaged economy (Michigan unemployment clocks in around 15%.) Gladys tells me about three babies born without brains — she suspects pesticides. She speaks about a man from Chiapas who hung himself when he found out that he had contacted AIDS — a priest was called upon to perform an exorcism at the house where he expired. And a young Triqui Indian mother from Oaxaca picking cucumbers for a Vlasic pickle contractor who was stranded in a country that doesn’t recognize her language after her husband went fishing for supper without a license and Fish & Game turned him over to the Migra.

We visit with Liliana (not her real name) from the drug war-riddled hot lands of Guerrero state. The patron is a kindly old farmer who has installed cable TV for the workers and we watch Barack Obama extol the wonders of his tarnished health care bill. Liliana’s husband is picking oranges in Florida but will soon return to work the cherry. She says he doesn’t much believe that an immigration reform measure will make it out of congress – “just some more blahblahblah…” But Liliana will march this May 1st if she can get a ride — undocumented workers are not permitted drivers’ licenses in the state of Michigan.

Traverse City is good to me. I perform at a local organic coffee roaster for a roomful of social change agents. The next morning, Jody T. who gave up her life to drive this garrulous old gaffer around the bioregion, steers the Viva into a trepidatious triangle. Cadillac was once the home base for Timothy McVeigh and the Michigan Militia, a recent flashback on the Ten O’clock News after a Christian posse purportedly targeted cops for blood sacrifice in preparation for the appearance of the Anti-Christ. To the west, small towns with Dutch-inflected names like Holland and Zeeland and Vreland dot the lakeside.

White clapboard outposts of the Dutch Reform Church, the architect of South African apartheid, their steeples spiring piously into the spring breeze, hug the highway. The Dutch Reform Church is the spiritual home of the Prinz family whose most celebrated spawn, Eric, is the go to guy at Blackwater. Further south we slide into Grand Rapids where the similarly affiliated DeVos dynasty’s Amway holds sway. The Prinzes and the DeVoses (a good reason not to root for the Orlando Magic) finance such repositories of right-wing fanaticism as Focus On The Family and Operation Rescue. The largesse of Dick DeVos rivaled the Mormon Church in putting California’s homophobic Proposition 8 over the top.

Grand Rapids, once the furniture capitol of the known universe and now the home of the Gerald Ford Museum of Presidential Imbeciles, is a good boxing town (Buster Mathis and Roger Mayweather have gyms here) and a swelling Latino population has changed the complexion of the city. Despite the downturn, Grand Rapids is trying to upgrade its downtown but the further one gets from the core of the city, the seedier things look.

Koinonia House is a sanctuary near the old demolished heart of Grand Rapids — in fact, it is the only structure left standing on its block. Established by disaffected seminarians like Jeff Smith in the early 1980s when the U.S. waged war on Central America, K House became a station on the underground railroad built by the Sanctuary Movement. The first refugees were Guatemalan Indians fleeing the scorched earth genocide of Efrain Rios Montt. In recent years, K House has taken in Mexicans fleeing that “desgraciada pobreza” back home, like Carlos and Alynn (their real names) who have brought their remarkable art with them to El Norte.

Jeff kicks back and reminisces about the fates of former tenants. The big-bellied wood stove belches out waves of warmth on a chill late March morning. The big arms of the fluffy old lounger envelop a weary traveler and hold him close. K House remains a sanctuary deep in the heart of a wounded land.

Stay tuned. Chicago, St Louis, Jackson Mississippi – there is still a whole lot of traveling to do as the Monstruo tour moves eastwards.

FIN

John Ross and “El Monstruo – Dread & Redemption in Mexico City” will visit St. Louis April 4th-7th, and Millsaps College Jackson Mississippi April 9th for a symposium on Mexico City – he will tour Baltimore, Washington, New York, and Boston April 19th through May 1st. For details write johnross@igc.org.