William Morgan Bennett, 1918-2010

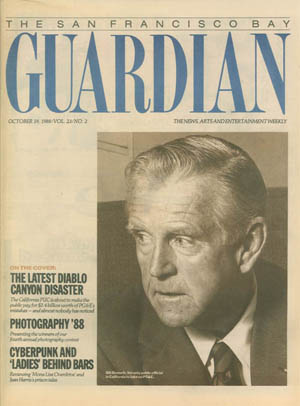

On the front page of the Guardian of Oct. 19, 1988, we ran a big picture of Bill Bennett with a caption that read: “Bill Bennett, the only public official in California to take on PG&E.”

The reason we featured Bennett was because the California Public Utilities Commission was poised to make yet another multi-billion giveaway to the Pacific Gas & Electric Company.

This time the CPUC would force the public to pay $3.4 billion worth of PG&E’s mistakes at its Diable Canyon nuclear power plant and not one public official in San Francisco, home of the PG&E/Raker Act scandal, and not one from any other public agency or public institution was on hand to monitor the CPUC hearings and testify about the horrible impacts the Diablo rate hike will have on the public.

The lone, honorable exception was Bill Bennett. Our editorial noted, “The only public official in California who has taken on the case is Bill Bennett, a member of the State Board of Equalization and a former member of the CPUC, a determined old warrior who fought Diablo from the start and continues to do so today, on his own, against the odds and at considerable personal cost.”

To drive the point home about Bennett’s couirageous stand, we continued, “Those who ignored the case–for example, the supervisors, mayor and city attorney of San Francisco, the board of directors of BART, the regents of the University of California and their counterparts in every other public agency and institution that pays or represents people who pay PG&E bills–ought to be ashamed. The citizens of every city, county and district ought to look at their representatives and ask: Where were you when PG&E walked away with all the marbles.”

The press in Northern California was ignoring the story, despite the colorful, forceful and newsworthy campaign that Bennett was waging. He said he had called the Chronicle and Examiner reporters to try to interest them in the story, but “it was useless so I gave up.” Guardian Reporter Jim Balderston did the story and quoted Bennett as saying, among other things, “This commission (the CPUC) must think long and hard of the welfare of the ratepayers and the shareholders of PG&E.” With no Bill Bennett on the CPUC, PG&E once again quietly walked away with billions in ratepayer money.

William Morgan Bennett, the public attorney who for more than five decades fought the corporate goliaths from taking all the marbles, died Feb.9th at his home in Kentfield after a short illness. He was 91. An overflow crowd paid tribute to his extraordinary life and career at services held on Feb. 12th at St. Patrick’s Church in Larkspur

When his daughter Joan phoned me about Bennett’s death, I realized once again how much the Guardian and the consumer and the rate-payer would miss Bennett. We are in the middle of PG&E’s biggest monopoly scam ever –Prop l6 and PG&E’s initiative to kill public power and community choice aggregation (CCA)– and Bennett is alas missing in action, for one of the first times in his life. Today, there are other public officials out there fighting PG&E, but there is nobody who can take on PG&E and its allies as effectively as Bennett.

Our 1988 story had a sidebar with the head, “Bennett vs. PG&E: The 30 years war.” The sidebar recounted an incident characteristic of Bennett and the way he gave new meaning to the term public service. In 1959 the El Paso/Pacific Northwest natural gas pipeline merger was all but approved by the CPUC, except for an appeal from Bennett as CPUC general counsel. Before Bennett could file the appeal, he got a phone call from Gregory Harrison, a partner in the politically powerful law firm of Brobeck, Phleger and Harrison. Harrison asked Bennett if he was going to file. Bennett said yes and Harrison responded, “I told them you would say that.”

Harrison told Bennett he would be removed from the case if he filed the appeal. Bennett told Harrison he was going to call a press conference. Harrison responded. “I told them you would say that,” and hung up. Shortly thereafter, Bennett got a call from Gov. Brown, who asked him if he was going to file the appeal. Bennett said yes and Brown refused to discuss the matter further.

Twenty minutes later, Bennett got a telegram from Brown that stated, “You no longer represent me or the State of California in USA v El Paso.” This infuriated Bennett and fueled his relentless 14-year crusade to compel El Paso to divest itself of Pacific Northwest. because of its price-fixing and monopolistic implications for California. In 1969, appearing as a private citizen, he successfully argued the final U.S. Supreme Court appeal in the case, the last oral argument heard by the Earl Warren court.

The Washington Monthly caught the drama and precedent of Bennett’s appearance in its November 1971 issue. “His last appearance before the court in 1969

needs to have been witnessed. Standing alone against an array of the best legal talent that could be provided by El Paso, the states of California and Utah, lawyers for other gas companies and the U.S. government, represented personally by Solicitor General Erwin Griswold, Bennett attacked as the lone surviving avenging angel of the original antitrust action. Finger in the air, voice crying out in toners of retribution, he spoke brilliantly and forcefully without notes for an hour…In the process, Bennett impressed at least one justice privately, and many more observers, as one of the most brilliant and effective lawyers to have gotten to his feet to present oral arguments to the court during the last 14 years.”

As the final footnote in this legal saga, Bennett stopped El Paso’s efforts in Congress to pass legislation to void the breakup of El Paso. The result: the largest refund for California ratepayers in the history of regulation to date. The decision set a national precedent in antitrust law.

Bennett was born Feb. 20, 1918 in San Francisco to Lt. William M. Bennett of the San Francisco Police Department and Eva Curran of Amador. He attended Most Holy Redeemer Elementary School, St. Ignatius High School, the University of San Francisco and the Hastings College of Law. At the outbreak of World War II, he suspended his law studies and joined the U.S. Army Air Corps.

He was a B-17 pilot in the North African, Mediterranean and European theater of operations, l5th Air Force, 483rd Bombardment Group, 815th Squadron, stationed in North Africa and then in Foggia, Italy. The 483rd flew a total of 215 combat missions during 14 months of combat duty and Bennett was in the middle of it all. “Wherever there were major oil refineries, aircraft and parts factories, tank works, railroad terminals and marshaling yards, supply dumps, bridges and communication networks, he saw action,” Jane Bennett said. He flew 35 missions and encountered severe flak and fighter attacks at some of the most heavily defended targets in Europe: Linz’ Herman Goering Tank Works; Berlin’s Daimler-Benz Tank Works; Innsbruck; Vienna; Regensburg; Blechhhammer; Schweinfurt; Salzburg; Landshut; Moosbierbaum, and Ruhland where ME 262 German jets attacked his squadron.

The Tuskegee Airmen, the famous black squadron, escorted Bennett’s missions. “Their base was right next to my father’s,” Joan Bennett said. “They were separated on the ground but equal in the air. That is, they were equal targets for the Germans.” Bennett often visited some of the fighters across the runway that segregated the blacks. George McGovern, the bomber pilot who later became a presidential candidate in l972, was stationed at a nearby base. He flew B-24s.

Bennett flew some of the first shuttle missions into Russia. As the bomber squadrons flew deeper into Germany, the planes did not have fuel or were too shot up to return to their base in Italy. So the squadrons continued on to Poltova, Russia, to get refueled and repaired, and then either flew back immediately back to their base or stayed over night and flew back the next day. The missions were kept secret during the war but later became known as the “Poltova missions.”

Of the original 646 crew members sent to Italy in March 1944, 38 per cent were killed or missing in action. His bomb group received numerous battle awards, including two outstanding unit presidential citations. Bennett was highly decorated and won three Oak Leaf Clusters, four Bronze Stars and the Distinguished Flying Cross. He was awarded the DFC for his courage and skill in miraculously bringing his plane back from a mission over Worgi, Austria, in February, 1945. Bennett’s plane was hit by heavy enemy fire and the two right engines were shot out. He told his crew to bail out but they refused because they counted on Bennett to pull them through. Bennett did, safely piloting his crippled plane over the Alps. When the plane limped back to its base in Italy, there was nothing left inside, because the crew had ditched everything to lighten the load.

Col. Paul L. Barton, Bennett’s commanding officer, pins the Distinguished Flying Cross on Bennett in a ceremony on May 12, l945, at the air base on the Sterparone farm in Foggia, Italy. Gen. Twining, head of the l5th Air Force who ended up as Chief of Staff of the USAF after the war, attended the ceremony. “There was no Tom Hanks, Brad Pitt, Tom Cruise WWII move glamor,” Bennett’s daughter Jane told me. “The base itself was primitive: steel mats for runways. Ankle deep mud in the winter along with snow, ice and rain. Open latrines, no toilet paper, tent-living with one crew per tent. No mess halls. One canteen of water per day, etc.” She said the Bennetts visited the farm in l982. “The runways were vineyards,” she recalled. “The briefing hall for the men still stands. The interior of white plaster is still lined with drawings of pinup girls. The young girl who lived on the farm during the war is now the owner of the family land. She was very gracious. She invited us in for coffee.”

After the war, Bennett finished law school at the University of San Francisco and then embarked upon a remarkable career of public service. Until I started working on his obituary, I knew nothing about Bennett’s distinguished war record as a bomber pilot. But it is clear to me that, having followed Bennett through the years, that his combat experience under artillery fire and with flak coming at him from all directions served him well in public life. He spent most of his public career as a tough, smart and aggressive attorney who relished taking on the big cases and the big corporate behemoths who were screwing the public on illegal mergers or monopoly rate increases. To him, this was just combat in a different theater of operations. Sometimes as a public attorney, sometimes acting as an individual citizen, he handled precedent-setting cases in antitrust, regulatory and criminal law and argued six times before the U.S. Supreme Court. He earned the nickname “the legal Houdini” but I always thought of him as “Fighting Bill” Bennett.

As a deputy attorney general, he successfully prosecuted public corruption trials in 1954-55 against the State Board of Equalization in San Diego and put l3 public officials in jail. From 1957-59, he handled the celebrated case of Caryl Chessman, known as “the redlight bandit.” After his argument before the U.S. Supreme Court, the court clerk quietly handed him a note from Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter. He wrote, “There is no reason why I should not tell you how admirably you represented the state in this important case.” The clerk told Bennett he should save the note because it was only the second such note that Frankfurter had ever written.

From 1957-58, Bennett represented the state before the CPUC and won many cases against utilities that resulted in hundreds of millions of dollars in ratepayer rebates. Gov. Brown appointed him chief counsel of the PUC in 1958.

In 1960 Bennett was invited to join Sen. John F. Kennedy’s campaign as an advance man canvassing a territory from Chicago to New York. He became friends with JFK and was considered part of Kennedy’s “Irish mafia.” Kennedy asked him to head the Federal Power Commission but he rejected it to remain with his family.

Bill Bennett and then presidential candidate John F. Kennedy are pictured in 1960 as they got off the campaign plane at O’Hare field in Chicago. Bennett was an advance man for JFK and helped stage several rallies in Chicago. Then JFK and Bennett headed east to Hamtramck, Michigan, and finished up at the garment center in New York. JFK asked Bennett to be head of the Federal Power Commission but Bennett turned the appointment down to remain in California with his family.

In 1962, after Brown appointed Bennett to the CPUC, he promptly took on PG&E with gusto. With the support of the Sierra Club, Bennett filed the lone dissenting opinion against the CPUC’s approval of a nuclear power plant upwind of San Francisco at Bodega Bay. The Bodega fight was started in the living room of Prof. Joe Neilands, a UC-Berkeley biochemistry professor and stoked along by the Neilands/CharlieSmith/David Pesonen gang, with help from the Chronicle and its executive editor Scott Newhall and environmental writer Harold Gilliam. The battle caught on and became a national story and focal point for the emerging anti-nuclear movement. PG&E was forced by public opinion to withdrew its application and skedall down to Diablo Canyon. And so did Bennett.

Bennett was later visited by the chairman of PG&E, Robert Gerdes. told Bennett, “We don’t mind you dissenting, but do you realize the Russians are trying to stop us from building atomic plants.”

During his CPUC tenure, Bennett led the commission to regularly reduce electricity and gas rates in response to rate cases before the commission. In 1968, then Gov. Ronald Reagan refused to reappoint Bennett to the commission and sent Bennett a letter apologizing for not being able to reappoint him. Reagan did not explain the reason. Before Reagan could kick him off the CPUC, Bennett had saved the consumers hundreds of millions of dollars. Ever after Bennett, the CPUC has operated on a supine basis with PG&E and other utilities and has handed down rate increases and goodies to them on a virtual assembly line basis.

I first met Bennett in 1967 in his CPUC office overlooking the Civic Center in the state building. Lee Fremstad, then the San Francisco correndent for the Sacramento Bee, took me in and introduced me. I had rarely seen a public official like Bennett. He knew about the Guardian and me, had some juicy story ideas for me, and a batch more for Fremstad. Fremstad bantered back and forth with Bennett, noting a couple of ideas but rejecting others as too much even for the Bee and its longtime public power posture. Bennett was open, expansive, full of Irish humor, a populist Democrat full of opinions I liked, jutting the Bennett jaw to make a point, and the kind of guy who might be good for a lively three martini lunch.

I thought he would have made a wonderful newspaper columnist or editorial writer, if he could find a newspaper that would publish his tough consumer-oriented opinions that so agitated the PG&Es and Hearsts of the region. We always enjoyed Bennett at the Guardian, endorsed and supported him and used him as a friendly source and inspiration.all through the years.

When Bennett left the CPUC, Neilands and Smith held an appeciation dinner for him in Berkeley that brought together the Bodega Bay/public power warriors of the era. This was a watershed moment for the Guardian and me. My wife Jean and I went, met Bennett and Neilands et al and got initiated. We also met Peter Petrakis, a fan of Bennett’s, and a graduate student of Neilands. Neilands did our pioneering expose of the PG&E/Raker Act scandal in l969. Petrakis joined the Guardian and followed up Neilands’ work with a series of investigative storiies that revived the scandal and the public power movement in San Francisco. Bennett, as I realized, was a catalyst.

Bennett’s next move to stay in public service was to run for the State Board of Equalization and Franchise Tax Board. He won his first campaign in l970 even though his opponent outspent him $450,000 to $4,000, all his own money. He was relected to five more terms, despite refusing to accept campaign contributions, and continued to fight the good fight against the special interests in Sacramento and beyond. He was also a professor of law at Hastings while on the board.

Bill Bennett with his wife Jane in 1943 at the primary cadet school in King City, Calif. They were married 67 years.

Bennett is survived by his wife of 67 years, Jane, and sons William (wife Gwendolyn) of Lafayette, James (Paula) of Kentfield, Michael (Roxanne) of Manhattan, Kansas, and daughter Joan of Kentfield and grandsons Jimmy, Will, Jack, and Brendan of Kentfield.

The Bennett family obituary sums up their patriarch: “Despite his friendships with president and esteemed jurists, his out-going nature was such that he was a friend to all. He was a populist democrat, consumer rights advocate, and a veritable David against the corporate world’s Goliaths, in the vein of his mentor and ultimately friend, Earl Warren. Even with such achievements, his most important and cherished career was as a father and family man. Upon retirement, he embarked upon his most rewarding and enjoyable career: a devoted, loving, entertaining husband, father, and grandfather. For them and through them, he will live forever ‘in his way.'”

For me, I will stick with our cutline under Bennett’s picture on our l988 front page: “Bill Bennett, the only public official in California to take on PG&E.”

The Bennett family photo was taken in May, 2009, at the Napa airport. A B-l7 was touring the country and Bennett wanted to see it. Jane Bennett said he actually went through the plane. “It was not easy. The access was a skinny, steep, metal ladder to the cockpit. I don’t know how he got up it. He refused a ride in the plane. As he said, ‘If I cannot fly it, what’s the point.'”