arts@sfbg.com

I’m from the city of gangstas and broken dreams / where we hopin’ the Lord hear our silent screams / but this dope money helpin’ my self-esteem — J Stalin, “Self-Destruction”

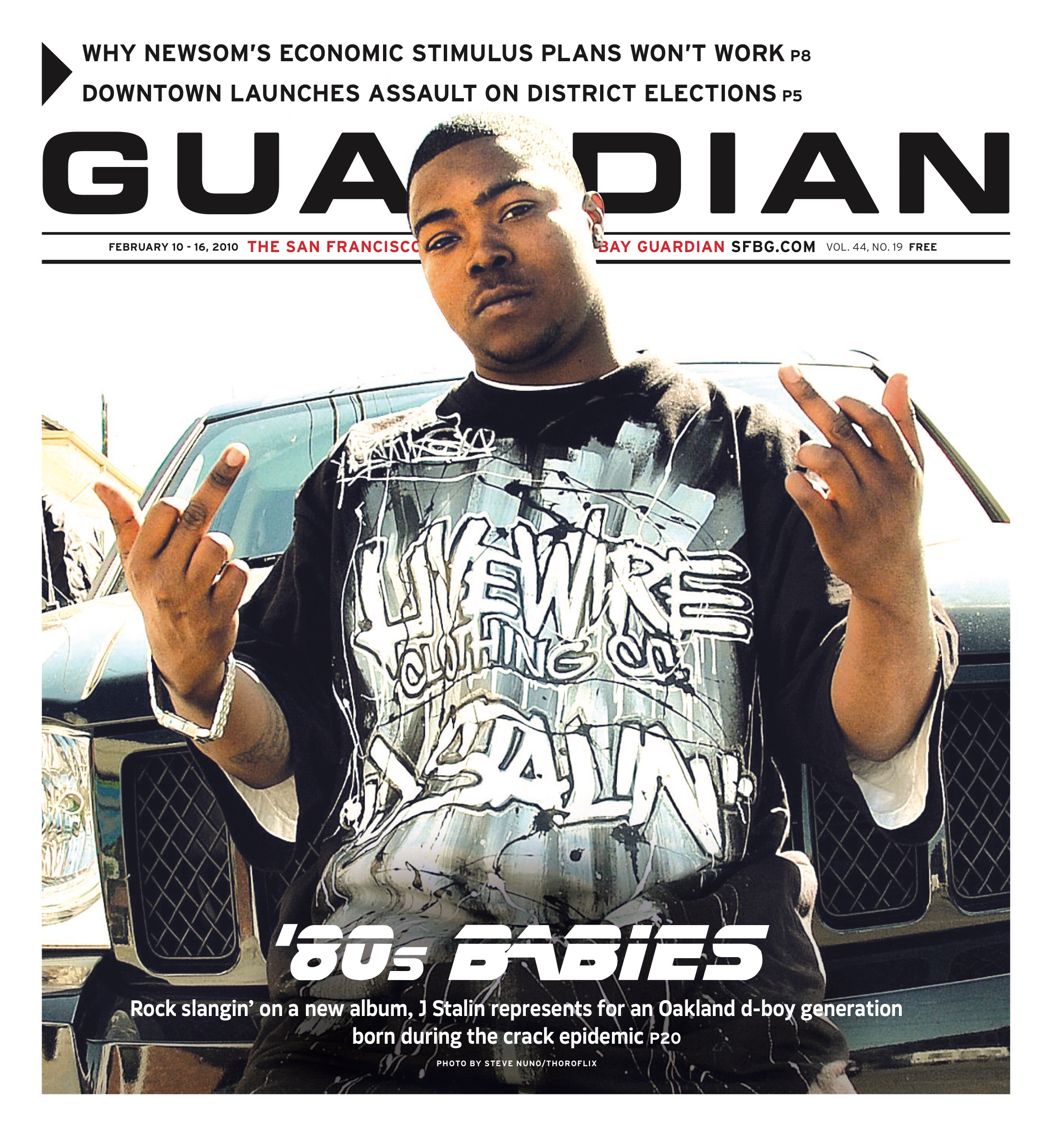

MUSIC I’ve known J Stalin for five years, during which I’ve watched the pint-sized, eternally baby-faced rapper develop from cocky adolescent to full-blown boss, head of a label and an ever-expanding crew of talent both known as Livewire. When we met, he’d already made a prestigious debut as an 18-year-old on Richie Rich’s Nixon Pryor Roundtree (Ten-Six, 2002), but he still had a long grind to get where he is now.

The title of “hottest rapper in Oakland” changes hands rapidly, but at the moment, it’s Stalin’s, coinciding with the recent release of his sophomore album, The Prenuptial Agreement (Livewire/SMC). “Sophomore” is misleading; J’s released countless projects since his first album, On Behalf of the Streets (Livewire/Zoo Ent, 2006) — not simply mixtapes, but full albums under one pretext or another, like a duo disc with Livewire-member Mayback, The Real World, Vol 2 (Livewire/DJ Fresh, 2008), or his entry in SMC’s Town Thizzness series, Gas Nation (2008). But these days, rappers reserve the right to designate “official solo albums” among their endless stream of releases, and J has patiently assembled Prenup over roughly three years.

“On Behalf of the Streets was to prove myself to Oakland,” he says. “When I made Prenup, I was trying to make music for the world. My fanbase is bigger than Oakland now, so I gotta make my music bigger.”

Prenup definitely succeeds in this ambition. The Mekanix — who produced all of Streets — return in force, alongside numerous newer producers like teenage Alameda resident Swerve. Tracks like Swerve’s “Neighborhood Stars” (blessed by Oakland’s godfather, Too Short, as well as Mistah FAB) or the Mekanix’s “HNIC” (featuring Messy Marv) are spacious, state-of-the-art numbers that hold up against anything on national radio.

Yet the core of Stalin’s sound is very Oakland — unsurprising, given his role in shaping the Town’s current obsession: the 1980s. Musically, the signatures of this trend are classic 808 beats, layered with old skool keyboards from a time when synths barely resembled the instruments they allegedly imitated. Aside from the 808s, the resulting tracks sound little like ’80s hip-hop (or even funk), evoking more the sonic palette of that decade’s R&B and even new wave.

DJ Fresh, producer of J’s first “pre-album” The Real World (Livewire/DJ Fresh, 2006) and other Livewire projects, acknowledges that these sounds have had a role in digital hip-hop. “That sound was there, but we mastered it,” he said. “Nobody was really touchin’ that sound before. It helped me find my sound, and it sounds natural with the way Stalin raps.”

“I just got it in me, those ’80s beats,” the often melodic Stalin concurs. “It probably got beat into my head as a child. I got a smooth style of rappin’, my harmonizing and all that. I’m on that ’80s melody vibe.”

ROCK OF AGES

Given the size and influence of Livewire, and its association with Beeda Weeda’s PTB crew, the ’80s vibe has gone viral in Oakland over the past couple of years. But unlike other miners of ’80s terrain — say, the Casio rock trend of last decade — the new sound of the Town has an organic lyrical connection through tales of crack and the devastation the drug has wreaked in the ghetto. “Slangin’ rocks” is hardly a novel topic in rap, yet there’s been a shift in presentation. This, I think, is a directly connected to age: unlike their elders, these new rappers are the first generation born during the crack epidemic. Born in West Oakland’s Cypress Village in 1983, Stalin himself is literally a crack baby.

“My mama been clean for two-and-a-half years,” Stalin says. “She did drugs all my life. We wasn’t always broke, because she sold drugs too. But as she got older, she started using more and selling less.”

This was a harsh environment for the young Jovan Smith. When J was only five, his 18-year-old brother, Lamar Jackson, died from swallowing his rocks while escaping from the police. Stalin’s dad, a con man, was in jail for most of Stalin’s childhood.

Stevie Joe — a Livewire rapper whose upcoming disc ‘80s Baby also refers to his East Oakland hood, the Shady 80s — succinctly articulates the effects of such an upbringing.

“A lot of kids grew up alone,” he says. “You gotta go outside because your parents tell you, ‘I’m getting high, get outta here.’ When you outside and they inside getting high, they don’t know what you doing out there. That’s how people get involved with selling drugs, doing drugs, all that.”

Immersed in this environment, Stalin became a d-boy — a teen crack dealer — standing on the corner, taking turns with his friends selling as customers came through. Stevie himself sold drugs more casually until age 19, when his daughter was born. “I never wanted to hit the block, but I needed a stable place where I could make money. It might sound bad on paper, but it helped me raise her.”

Others, like Livewire’s Philthy Rich, whose Town Thizzness disc Funk or Die (SMC) dropped in late ’09, began even earlier. Hailing from East Oakland’s Seminary neighborhood, Philthy caught his first case at age 11 for stealing a bike, before graduating to the dope game.

“I got in the streets when I was young because I had a rough parenthood,” he said. “A single mother. Five different kids from five different fathers. For attention I was rebelling. And it’s not hard to start selling drugs when you already been around that life. Most of the crackheads is people’s family from the neighborhood. So it’s nothing new.

“It was just me out there, trying to find myself,” he continued. “I used to wonder why I was even born.”

D-BOY BLUES

In lyrical terms, the ’80s baby generation primarily identifies with classic Bay Area mob music, bypassing more recent hyphy. But there seems to be a difference in presentation. The ’90s mob rapper tended to rap from an adult perspective, portraying himself in hyperbolic exploits as a kind of Scarface-inspired action figure. To be sure, the ’80s babies haven’t abandoned such tales of million-dollar deals, speedboats, and private planes. But alongside this, the story of the d-boy has emerged, reflecting the trauma of the generation’s upbringing. In contrast to the mobster’s comic-book glory, d-boy stories are frequently anti-glamour in tone, from the mundane, heartbreaking experiences of neglect — wearing the same clothes for a week or more being a common detail — to the painful tragedies of losing parents and siblings to drugs or murder. These stories generally unfold against a middle-school or high-school backdrop and are narrated from a present-tense, first-person perspective. The popularity of Stalin and ’80s-baby peers partly stems from the bond these narratives create between a rapper and his young ghetto fanbase. They can appreciate and admire Stalin as the grownup mobster who measures dope by the kilo, but they can identify with J as the d-boy with a bundle of rocks and “dope fiend” mother.

“They relate to us because we talking about what they going through too,” Stalin says. “I was 17 once upon a time. I can still relate; you just got to remember. I remember when I was 12. I can relate to a 12-year-old.”

Despite his chaotic childhood, Stalin wound up one of the lucky ones. Busted at 17, with a weekday curfew and weekends in juvenile hall, he had time on his hands and, like Mac Dre and many others, he used this isolation to begin writing raps. As it turned out, his late brother’s best friend grew up to be DJ Daryl, who produced 2pac’s 1993 smash “Keep Ya Head Up.” Daryl took Stalin under his wing, eventually introducing J to Richie Rich, who was impressed enough to feature Stalin on several tracks on Nixon. For Philthy Rich — subject of a segment in the recent, somewhat histrionic Discovery TV documentary Gang Wars: Oakland (2009) — as well as Stevie Joe, getting off the block took a lot longer.

“After I had my second son,” says Philthy, “I needed to do something else than what I was doing, in and out of jail. The cycle was just going to repeat. I feel like I can get further doing this.”

A chance encounter with Keak da Sneak manager Dame Fame, who was impressed with the rapper’s talents, helped get Stevie off the block and into the recording studio.

“I backslid one time, after a couple of months,” he admits. “But that didn’t last long because I couldn’t do it no more. So every day since I been rappin’.”

While J, Stevie, and Philthy have left the d-boy life behind, they haven’t forgotten the struggles they went through. The pain of this music offers solace to today’s disaffected youth, who, given the cumulative social effects of crack, are wilder than ever.

“These motherfuckers are crazy, because they never been raised,” Stevie says, citing the passing of pre-crack generations in the hood. These are the kids the new brand of “conscious thug” reaches out to. Alongside glorified tales of killing and dealing, the rappers send out more cautionary messages. Stalin voices the paradox on the intro to Prenup: “I told them I sold rocks on MTV / I’m a hustla, I could sell a million mp3s / and still send the message ‘don’t sell drugs’ to teens.” “As black people, we adapted to the ghetto to where we feel like there’s nothing wrong with us,” Stalin says. “It’s like nobody sees the big picture. It seem like nobody have big dreams of getting out the ghetto. They content; fuck being content — strive for more. Like OK, I sold drugs, but when I die, my obituary’s not going to say ‘drug seller.’ My obituary’s something whole different.”