The White Meadows (Mohammad Rasoulof, Iran, 2009) This latest by the recently jailed Iranian director of Iron Island (2005) is a stark, visually striking allegory whose natural settings (the salt formations of Lake Urmia) could hardly be more surreal. Aging Rahmat (Hasan Pourshirazi) rows his little boat from one tiny island community to another, collecting tears from variably aggrieved locals so they can be absolved of their sins — just how, neither they or we know. During his latest travels he gains a teenaged stowaway, then a blind-struck painter as passengers; witnesses a couple of village rituals that prove fatal for their main participants; and experiences other curious events that scarcely prompt a raised eyebrow from him. As with so much modern Iranian cinema, Mohammad Rasoulof’s film carefully renders its political symbolism so abstract you can dig endlessly for hidden meanings, or simply lose yourself in the hypnotic black-and-white-in-color imagery of black-clad people on bleached landscapes. Fri/23, 6:30 p.m., Kabuki; Sat/24, 9:30 p.m., Kabuki; Sun/25, 8 p.m., PFA. (Dennis Harvey)

Nymph (Pen-ek Ratanaruang, Thailand, 2009) Boy meets girl. Boy and girl fall in love. Girl cheats on boy with boss. Boy falls in love with tree. So are the broad strokes of Thai director Pen-ek Ratanaruang’s jungle-horror, Nymph, a city-to-country romance that deftly weaves strands of urban anomie, sexual dysfunction, and rural mythos into a dreamy, arboreal fantasia. One might be tempted to reference Lars von Trier’s Antichrist (2009) and fellow Thai helmer Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s 2004 breakout, Tropical Malady, as obvious points of reference, but that would derogate the potency and intensity of Ratanaruang’s singular, artistic design. The director of Last Life in the Universe (2003) and Ploy (2007) creates a tropical mise-en-scène that is less cinematic than immersive, developed largely by his use of tight, suspenseful close-ups, fluid camera work (including a 10-minute opening sequence that is practically gymnastic), and a transfixing ambient score. But unlike Tropical Malady, which leveraged much of its second-half’s novelty from overwrought, homoerotic tropes and a condescending nativism, Nymph‘s descent into the jungle is only the beginning of this powerful love story. Fri/23, 9 p.m., Kabuki; Sat/24, 4:30 p.m., Kabuki; April 28, 4:45 p.m., Kabuki. (Erik Morse)

Around a Small Mountain (Jacques Rivette, France/Italy, 2009) Around a Small Mountain (or 36 vues du Pic Saint Loup) is New Wave doyen Jacques Rivette’s return to the whimsy of 1984’s Love on the Ground, another exploration of theater staring eternal demoiselle Jane Birkin. In Mountain, Birkin plays Kate, a prodigal daughter who has returned to her deceased father’s circus after an unspecified trauma forced her into a 15 year absence. En route she encounters Vittorio (Sergio Castellitto), a peripatetic who instantly discovers in Kate a fellow improviser for his acrobatic feats of conversation. In hopes of learning her secret past, Vittorio follows Kate and her shabby troupe from performance to performance through the tiny towns of the Cevennes. Along the way, Rivette treats his audience to a mish-mash of sideshow sketches, enchanting dialogues and haunting soliloquies, all beneath the magical totem of the big top. The film is spellbinding ode to the theatre of everyday life and the actors who prance in and out of its cirque. Fri/23, 9:30 p.m., Kabuki; Sat/24, 4:15 p.m., Kabuki; April 28, 6:30 p.m., PFA. (Morse)

Way of Nature (Nina Hedenius, Sweden, 2008) Save for when Werner Herzog is doing the talking, documentaries about the natural world often benefit from a lack of voiceover narration. Nature’s seasons, cycles, and rhythms provide their own narrative structure, and simply, silently observing what happens can make for fascinating viewing. Nina Hedenius understands this. Her engrossing year-in-the-life portrait of Lisselbäcka Farm in northern Sweden is cut around creatures great and small — horses, cows, goats, chickens, dogs — and their routines. Although humans are part of the bucolic scene Hedenius so meticulously orchestrates (the sound editing is such that the film would be no less immersive if you watched it blindfolded), they are merely supporting actors. After watching, for the fourth time, another gangly offspring leap to its feet, minutes after being born, you start to realize the ways in which our species is quite helpless. If their keepers suddenly passed away, the animals of Lisselbäcka — domesticated though they may be — would probably manage to carry on. The way of nature is instinct, not mastery. Sat/24, 2 p.m., PFA; Sun/25, 3:45 p.m., Kabuki; Mon/26, 1 p.m., Kabuki; April 28, 6:30 p.m., Kabuki. (Matt Sussman)

Between Two Worlds (Vimukthi Jayasundara, Sri Lanka, 2009) Part vision quest, part historical allegory, Vimukthi Jayasundara’s lush and beguiling head-scratcher unfolds like the mutable folktale told between two fishermen in one of the film’s asides. A synopsis would go something like this: an unnamed South Asian man falls from the sky into an unspecified South Asian country (although the Sinhala the actors speak places us in Sri Lanka) under siege by revolutionaries intent on destroying all means of communication and killing any remaining young men. Fleeing a riot-ravaged city he winds up in the countryside where he reconnects with his sister-in-law, and undergoes several mysterious and mystical experiences at a nearby lake. “It’s possible that one can see today what has happened in the past,” cautions an old man to our protagonist, and Jayasundara — with an eye for arresting mise-en-scene, gorgeously photographed by Channa Deshapriya — attempts to offer a way to re-see the traumas of the civil war that ravaged Sri Lanka for over three decades. Like a freshly remembered dream, Between Two Worlds is as stubbornly oblique as it is hard to shake. Sat/24, 6:15 p.m., Kabuki; Sun/25, 9 p.m., Kabuki; Mon/26, 9:15, Kabuki. (Sussman)

Transcending Lynch (Marcos Andrade, Brazil, 2010) Picture it: everyone’s favorite psycho-thriller filmmaker and coffee retailer waxing beatific about peace, love, and “infinite bliss,” his American Spirit–stained teeth frozen in a perma-grin as he extols the virtues of the “unified field” of consciousness. At certain moments in Transcending Lynch, an exploration of infamous auteur David Lynch and his 35-year devotion to transcendental meditation, the director comes across as flakier than the celebrated piecrust at Twin Peaks‘ Double R diner. (At one point he even utters the phrase “Holy jumping George!”) For the irony-soaked, all the TM talk may be a little TMI, but for Lynch the practice is nothing short of the very source of his creative wellspring. Marcos Andrade’s documentary, which follows Lynch on a 2008 Brazilian book tour, won’t offer the mad-genius Eagle Scout’s more rabid followers much new insight. While the movie strives to be meditative, it’s more of an amalgam of trippy travelogue and pitch meeting. Even more frustrating, we get only teasing glimpses of how TM has directly informed and impacted the artist’s work. Lynch may be on the path to universal enlightenment, but when it comes to the man himself, the rest of us ignoramuses are still mostly in the dark. Sat/24, 6:30pm, Kabuki; Mon/26, 9pm, Kabuki; Tues/27, 12:30pm, Kabuki. (Michelle Devereaux)

14-18: The Noise and the Fury (Jean-Françoise Delassus, France/Belgium, 2009) Made for French TV, Jean-Françoise Delassus’ unclassifiable film would be arresting simply for cobbling together seldom-seen archival footage reflecting all aspects of the First World War, from its leaders to its trenches. But he and co-scenarist Isabelle Rabineau have shaped that footage into a narrative driven by the writings of a (fictional) French everyman soldier who somehow manages to survive and serve in most of its major conflicts. The result melds exquisite color tinting, first-person narration, clips from commercial films about the war (by D.W. Griffith and Chaplin as well as European directors), and ambient sound to create a brilliant kind of living history lesson that makes the events of nearly a century ago seem as immediate as yesterday’s. Mon/26, 4:30 p.m., Kabuki; May 1, 2 p.m., Kabuki; May 3, 9 p.m., Kabuki. (Harvey)

The Peddler (Eduardo de la Serna, Lucas Marcheggiano, and Adriana Yurkovich, Argentina, 2009) Daniel Burmeister is a traveling filmmaker. He drives his infirm jalopy from one small Argentine town to the next, hoping to set up camp for a month and make a movie with the locals. He’ll need food, a place to stay, and a camera. Whatever camera they can find. Usually the mayors are easy to convince, because Burmeister is essentially a regional attraction, a one-man circus they know about from the neighboring towns. It’s this strange repurposing of the filmmaking experience that makes the documentary so distinctive and special. And just watching the old man hustle from shot to shot with his bashful actors, working efficiently from one of the handful of scripts he’s been cycling through for years, is an absolute pleasure. Directors Eduardo de la Serna, Lucas Marcheggiano, and Adriana Yurcovich capture the jury-rigged process with unobtrusive admiration and an absence of condescension. As I watched it I kept thinking it was like the soul that was missing from Michel Gondry’s 2008 warmed-over DIY manifesto Be Kind Rewind. Mon/26, 6:30 p.m., PFA; May 1, 12:30 p.m., Kabuki; May 4, 6:30 p.m., Kabuki. (Jason Shamai)

Russian Lessons (Olga Konskaya and Andrei Nekrasov, Russia/Norway/Georgia, 2010) I remember watching the news two summers ago and feeling confused by the details of the Russia-Georgia War, the culmination of a dispute over the territory of South Ossetia. There seemed to be a haziness about who started what. Russian Lessons offers Olga Konskaya and Andrei Nekrasov’s version of what happened that summer and indicts Russian and mainstream international news organizations for exactly that failure to present a satisfactory chronology. Konskaya, a theater director and documentary producer, filmed events as they unfolded on the Northern end of the conflict while Nekrasov, a veteran documentarian, filmed in the South. The result is a collection of interviews with residents of recently bombed Georgian towns, confrontations with Russian soldiers, and investigations of still-smoldering battle sites. The filmmakers spend an equal amount of time scrutinizing source footage from the war and its antecedents, exposing how it was used to mislead the international community. It’s a disturbing and persuasive rebuttal to the Putin administration’s official side of the story. April 28, 3:15 p.m., Kabuki; April 29, 12:30 p.m., Kabuki; May 1, 6:15 p.m., Kabuki. (Shamai)

Restrepo (Tim Hetherington and Sabastian Junger, USA, 2010) Starting mid-’07, journalists-filmmakers Tim Hetherington and Sebastian Junger spent some 15 months off and on embedded with a U.S. Army platoon in Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley, a Taliban stronghold with steep, mountainous terrain that could hardly be more advantageous for snipers. Particularly once a second, even more isolated outpost is built, the soldiers’ days are fraught with tension, whether they’re ordered out into the open on a mission or staying put under frequent fire. Strictly vérité, with no political commentary overt or otherwise, the documentary could be (and has been) faulted for not having enough of a “narrative arc” — as if life often does, particularly under such extreme circumstances. But it’s harrowingly immediate (the filmmakers themselves often have to dive for cover) and revelatory as a glimpse not just of active warfare, but of the near-impossible challenges particular to foreign armed forces trying to make any kind of “progress” in Afghanistan. April 30, 3:45 p.m., Kabuki; May 2, 4:15 p.m., PFA; May 4, 9:30 p.m., Kabuki. (Harvey)

Animal Heart (Séverine Cornamusaz, France/Switzerland, 2009) This first feature by Séverine Cornamusaz has a story that would have fit just as well into the cinema of 1920 — or the literature of Thomas Hardy or George Eliot 50 years earlier. Paul (Olivier Rabourdin) is the gruff owner of family lands in the Swiss Alps, raising livestock whom he treats better than wife Rosine (Camille Japy). When he’s forced to hire a seasonal hired hand in the form of Eusebio (Antonio Bull), the easygoing Spaniard’s concern for ailing Rosine incites not Paul’s compassion but his brute jealousy. This elemental triangle set amid the severe elements of its spectacularly shot setting has a suitably blunt (but not crude) power; it leads not where you might expect but to a hard-won fadeout of audacious intimacy. April 30, 4 p.m., Clay; May 2, 9:15 p.m., Clay; May 3, 6 p.m., Kabuki. (Harvey)

Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Inferno (Serge Bromberg and Ruxandra Medrea, France, 2009) A painstaking craftsman who left nothing to chance, French suspense master Clouzot (1955’s Diabolique, 1953’s The Wages of Fear) decided to push his own envelope a little in 1964. He cast Serge Reggiani as a resort innkeeper who becomes pathologically, paranoically possessive of his gorgeous wife (Romy Schneider). Convincing himself she’s having an affair, he gradually snaps tether — and the film itself would reflect that downward spiral by increasingly illustrating his mental stage in distortive image and sound. Unfortunately, the project also drove Clouzot mad in a way, as his grapplings at a new filmic language ran counter to the kind of creative discipline that normally storyboarded everything within an inch of its life. Shooting endless footage, spending endless money, he finally admitted defeat and abandoned ship. Never completed, the film’s surviving pieces were restored for this absorbing unmaking-of documentary — even if the original clips, daring then but now looking like psychedelic kitsch, suggest Inferno would likely have been no masterpiece but a fascinating, instantly-dated failure. May 2, 1:45 p.m., Kabuki; May 5, 6:15 p.m., Kabuki. (Harvey)

Presumed Guilty (Roberto Hernández and Geoffrey Smith, Mexico, 2009) A fan of true crime TV programming, I all but take for granted that little coda at the end of each episode reminding viewers that the suspects shown are innocent until proven guilty. I sometimes forget that such rights are not the case in all countries, such as in Mexico where the criminal justice system employs a reverse practice requiring the accused to prove themselves innocent. In Presumed Guilty, filmmakers, lawyers, and UC Berkeley students Roberto Hernández and Layda Negrete use rarely-seen, up-close footage of the Mexican trial process in their effort to exonerate a young Mexico City street vendor who is falsely accused of murder in 2005. The proceedings, which require the defendant to stand for hours on end and are performed sans jury, is riveting stuff for fans of those A&E true crime shows and is sure to ruffle the feathers of a few sympathetic humanitarians. May 2, 3:30 p.m., Kabuki; May 3, 6:30 p.m., PFA; May 6, 3:15 p.m., Kabuki. (Peter Galvin)

Lebanon (Samuel Maoz, Israel, 2009) “Das Boot in a tank” has been the thumbnail summary of writer-director Samuel Maoz’s film in its festival travels to date, during which it’s picked up various prizes including a Venice Golden Lion. On the first day of Israel’s 1982 invasion (which Maoz fought in), an Israeli army tank with a crew of three fairly green 20-somethings — soon joined by a fourth with even less battle experience — crosses the border, enters a city already halfway reduced to rubble, and promptly gets its inhabitants in the worst possible fix, stranded without backup. Highly visceral and, needless to say, claustrophobic (there are almost no exterior shots), Lebanon may for some echo The Hurt Locker (2009) in its intense focus on physical peril. It also echoes that film’s lack of equally gripping character development. But taken on its own willfully narrow terms, this is a potent exercise in squirmy combat you-are-thereness. May 2, 9 p.m., Kabuki; May 5, 9:30 p.m., Kabuki. (Harvey)

The Day God Walked Away (Philippe van Leeuw, France/Belgium, 2009) Director Philippe Van Leeuw states in the press materials that he made The Day God Walked Away in an attempt to understand how the assassins of the 1994 Rwandan genocide could do what they did and how others could stand by and watch. I walked away from Day with a better understanding of what might draw a person to choose defeatism over an unlikely survival. The film opens as a Tutsi housekeeper (Ruth Nirere) finds herself trapped in her Belgian employers’ house, fearing for her children and surrounded by gun-toting murderers. Light on scripted dialogue and featuring local actors, van Leeuw’s nonintrusive filming lends the film an authentic atmosphere that can be slow but is never boring. In lensing the film’s horrific scenes in a simple and matter-of-fact fashion, he eerily replicates the emotional separation that survivors of the massacre were forced to adopt in order to live. May 3, 6:45 p.m., Clay; May 4, 4 p.m., Kabuki; May 5, 4:15 p.m., Kabuki. (Galvin)

The Practice of the Wild (John J. Healey, USA, 2009) “The way I want to use ‘nature’ is to refer to the whole of the physical universe,” explains the poet Gary Snyder in John J. Healy’s succinct but penetrating documentary on the octogenarian poet, essayist, and environmental activist. Snyder’s expansive definition conjoins the two areas to which he has devoted his life and creative practice to better being at peace with: the terrestrial and the existential. Healey provides the back story — covering Snyder’s farmstead childhood, his discovery of his love for the outdoors, his association with the Beats and later immersion in Zen Buddhism, and his two marriages — told in part through the obligatory scan-and-pan photography and contextual talking heads. The film’s highpoints, however, are the many lively conversations Snyder engages in with his friend and fellow writer Jim Harrison, whose grizzled countenance and chirpy demeanor make him a character in his own right. May 3, 6:45 p.m., Kabuki; May 5, 1:30 p.m., Kabuki. (Sussman)

Joan Rivers: A Piece of Work (Ricki Stern and Annie Sundberg, USA, 2010) Whether you’re a fan of its subject or not, Ricki Stern and Annie Sundberg’s documentary is an absorbing look at the business of entertainment, a demanding treadmill that fame doesn’t really make any easier. At 75, comedian Rivers has four decades in the spotlight behind her. Yet despite a high Q rating she finds it difficult to get the top-ranked gigs, no matter that as a workaholic who’ll take anything she could scarcely be more available. Funny onstage (and a lot ruder than on TV), she’s very, very focused off-, dismissive of being called a “trailblazer” when she’s still actively competing with those whose women comics trail she blazed for today’s hot TV guest spot or whatever. Anyone seeking a thorough career overview will have to look elsewhere; this vérité year-in-the-life portrait is, like the lady herself, entertainingly and quite fiercely focused on the here-and-now. May 6, 7 p.m., Castro. (Harvey)

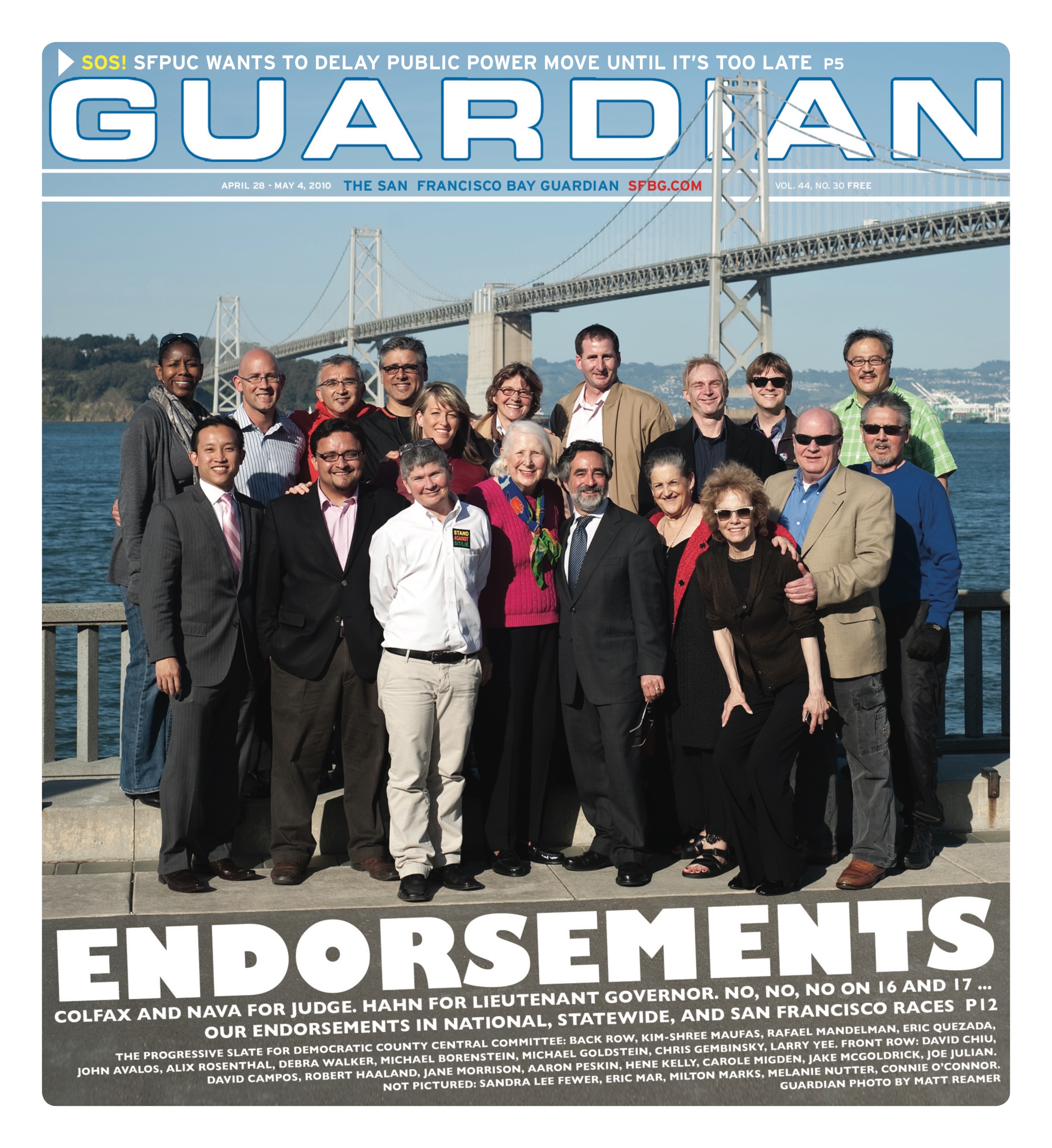

THE 53RD SAN FRANCISCO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL runs April 22–May 6 at Sundance Kabuki Cinemas, 1881 Post, SF; Clay Theatre, 2261 Fillmore, SF; Castro Theatre, 429 Castro, SF; and the Pacific Film Archive, 2575 Bancroft, SF. Tickets (most shows $12.50) are available by calling (925) 866-9559 or by visiting www.sffs.org>.