tredmond@sfbg.com

Former Mayor Willie Brown says that choosing a person of color for a leadership position should be a progressive value. Board of Supervisors President David Chiu says the new mayor, Ed Lee, is a progressive. Several supervisors and other political observers say the six-vote progressive majority on the board is gone.

And nobody really talks about what that word means.

Progressive is a term with a long political vintage, but it’s changed (as has the political context) since the 1920s. (Progressives these days aren’t into Prohibition.) So I’m going to take a few minutes to try to sort this out.

I used to tell John Burton, the former state senator, that a progressive was a liberal who didn’t like real estate developers. But that was in the 1980s, when the Democratic Party in town was funded by Walter Shorenstein and other developers who were happy to be part of the party of Dianne Feinstein, happy to be liberals on some social issues (Shorenstein insisted that the Chamber of Commerce hire and promote more women), and happy to promote liberal candidates like John and Phil Burton for state and national office — as long as they didn’t mess with the gargantuan money machine that was high-rise office development in San Francisco.

But these days it’s not all about real estate; it’s that the level of economic inequality in the United States has risen to levels unseen since the late 1920s. So I sat down on a Saturday night when the kids went to bed(yeah, this is my social life) and made a list of what I think represent the core values of a modern American progressive. It’s a short list, and I’m sure there’s stuff I’ve left off, but it seems like a place to start.

This isn’t a litmus test list (we’ve endorsed plenty of people who don’t agree with everything on it). It’s not a purity test, it’s not a dogma, it’s not the rules of entry into any political party … it’s just a definition. My personal definition.

Because words don’t mean anything if they don’t mean anything, and progressive has become so much of a part of the San Francisco political dialogue that it’s starting to mean nothing.

For the record: when I use the word "progressive," I’m talking about people who believe:

1. That civil rights and civil liberties need to be protected for everyone, even the most unpopular people in the world. We’re for same-sex marriage, of course, and for sanctuary city and protections for immigrants who may not have documentation. We’re also in favor of basic rights for prisoners, we’re against the death penalty, and we think that even suspected terrorists should have the right to due process of law.

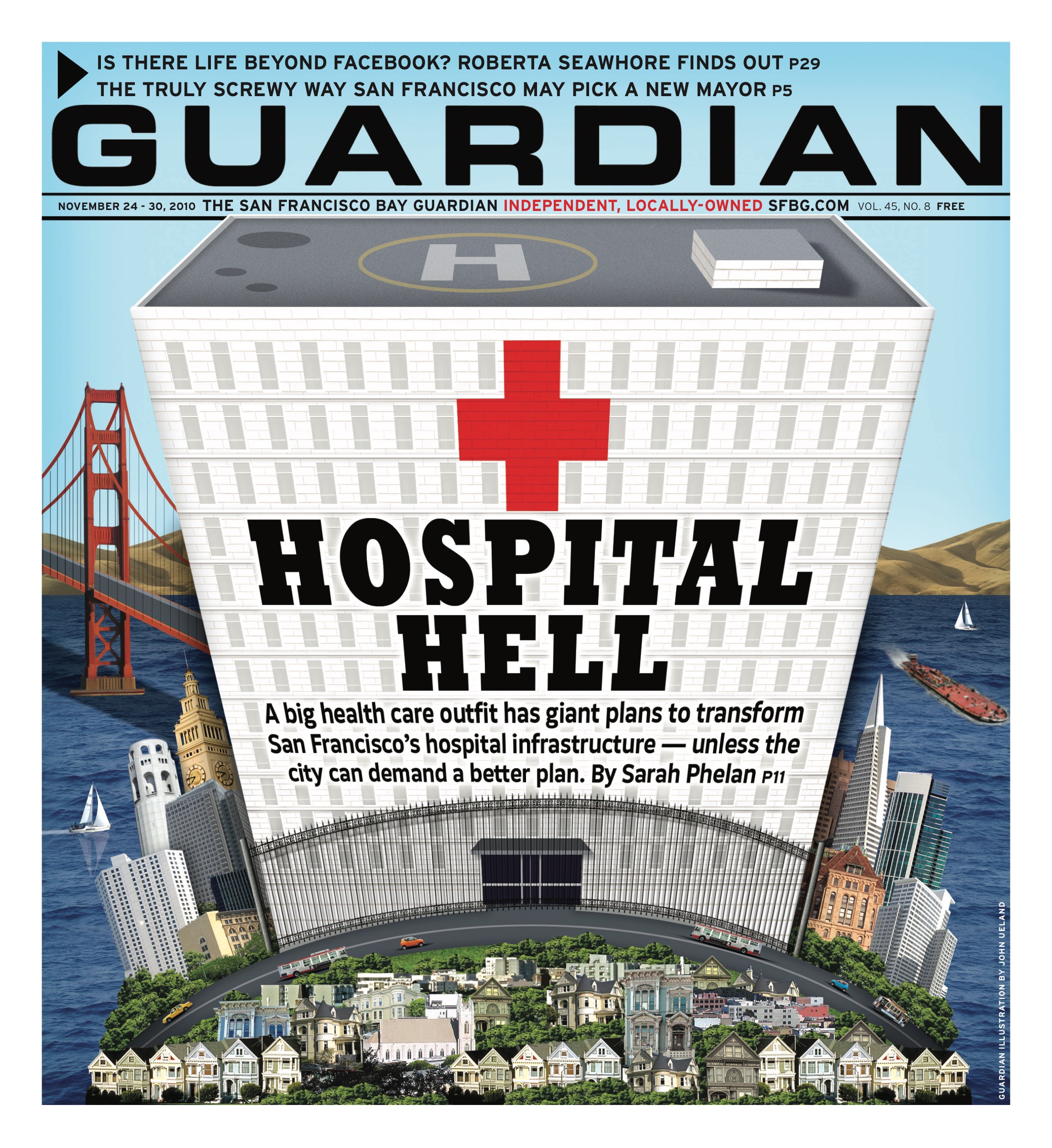

2. That essential public services — water, electricity, health care, broadband — should be controlled by the public, not by private corporations. That means public power and single-payer government run health insurance.

3. That the most central problem facing the city, the state, and the nation today is the dramatic upward shift of wealth and income and the resulting economic inequality. We believe that government at every level — including local government right here in San Francisco — should do everything possible to reduce that inequality. That means taxing high incomes, redistributing wealth, and using that money for public services (education, for example) that tend to help people achieve a stable middle-class lifestyle. We believe that San Francisco is a rich city, with a lot of rich people, and that if the state and federal government won’t try to tax them to pay for local services, the city should.

4. That private money has no place in elections or public policy. We support a total ban on private campaign contributions, for politicians and ballot measures, and support public financing for all elections. Corruption — even the appearance of corruption — taints the entire public sector and helps the fans of privatization, and progressives especially need to understand that.

5. That the right to private property needs to be tempered by the needs of society. That means you can’t just put up a highrise building anywhere you want in San Francisco, of course, but it also means that the rights of tenants to have stable places for themselves and their families to live is more important than the rights of landlords to maximize return on their property. That’s why we support strict environmental protections, even when they hurt private interests, and why be believe in rent control, including rent control on vacant property, and eviction protections and restrictions on condo conversions. We think community matters more than wealth, and that poor people have a place in San Francisco too — and if the wealthier classes have to have less so the city can have socioeconomic diversity, that’s a small price to pay. We believe that public space belongs to the public and shouldn’t be handed over to private interests. We believe that everyone, including homeless people, has the right to use public space.

6. That there are almost no circumstances where the government should do anything in secret.

7. That progressive elected officials should use their resources and political capital to help elect other progressives — and should recognize that sometimes the movement is more important that personal ambitions.

I don’t know if Ed Lee fits my definition of a progressive. He hasn’t taken a public position on any major issues in 20 years. We won’t know until we see his budget plans and learn whether he thinks the city should follow Gavin Newsom’s approach of avoiding tax increases and simply cutting services again. We won’t know until he decides what to tell the new police chief about enforcing the sit-lie law. We won’t know until we see whether he keeps Newsom’s staff in place or brings in some senior people with progressive values.

I agree that having an Asian mayor in San Francisco is a very big deal, a historic moment — and as Lee takes over, I will be waiting, and hoping, to be surprised.