EDITORIAL The first time a group of activists from across San Francisco met in a Community Congress, it was 1975 and the city was in trouble. Runaway downtown development was creating massive displacement and threatening the quality of life. Rents were rising and tenants were facing eviction. An energy crisis had left residents and businesses with soaring power bills. The manifesto of the Congress laid out the problem:

"Every poor and working class community in San Francisco has learned the hard way that its interests are at the bottom of the list as far as City Hall is concerned. At the top of the list are the banks, real estate interests, and large corporations, who view San Francisco not as a place for people to live and work and raise families, but as a corporate headquarters city and playground for corporate executives. By using their vast financial resources, they have been able to persuade local government officials that office buildings, hotels, and luxury apartments are more important than blue-collar industry, low-cost housing and decent public services and facilities."

The Community Congress hammered out a platform — a 40-page document that pretty much defined what progressive San Francisco believed in and wanted for the city. It included district elections of supervisors, rent control, public power, a requirement that developers build affordable housing, and a sunshine ordinance — in fact, much of what the left has accomplished in this town in the past 35 years was first outlined in that document.

Beyond the details, what the platform said was profound: it suggested that the people of San Francisco could reimagine their city, that local government could become a force for social and economic change on the local level, even when politics in Washington and Sacramento were lagging behind. It called for a new relationship between San Franciscans and their city government and looked not just at what was wrong, but what was possible.

That’s something that too often gets lost in political debate today. With urban finances in total collapse, the progressives are on defense much of the time, trying to save the basic safety net and preserve essential programs and services. It seems as if there’s little opportunity to talk about a comprehensive alternative vision for San Francisco.

But bad times are great times to try new ideas — and when the second Community Congress convenes Aug. 14 and 15 at the University of San Francisco, that’s exactly what they’ll be trying to do. It’s not going to be easy — the left in San Francisco has always been fractious, and there’s no consensus on a lot of central issues. But if the Community Congress attracts a broad enough constituency and develops a coherent platform that can guide future political organizing efforts, it will have made a huge contribution to the city.

The event also offers the potential for the creation of a permanent progressive organization that can serve as a forum for discussion, debate, and action on a wide range of issues. That’s something the San Francisco left has never had. Sup. Chris Daly tried to create that sort of organization but it never really worked out. The city’s full of activist groups — the Tenants Union, the Harvey Milk LGBT Club, the Sierra Club, and many others — that work on important issues and generally agree on things, but there’s no umbrella group that can knit all those causes together. It may be an impossible dream, but it’s worth discussing.

The organizers of the Community Congress discuss some of their agenda in the accompanying piece on this page. It should be based on a vision of what a city like San Francisco can be. Think about it:

This can be a city where economic development is about encouraging small businesses and start-ups, where public money goes to finance neighborhood enterprises instead of subsidizing massive projects.

This can be a city where planning is driven by what the people who live here want for their community, not by what big developers can make a profit doing.

This can be a city where housing is a right, not a privilege, where new residential construction is designed to be affordable for the people who work here.

This can be a city where renewable energy powers nearly all the needs of residents and businesses and where the public controls the electricity grid.

This can be a city where the wealthy pay the same level of taxes that rich people paid in this country before the Reagan era, where the individuals and corporations that have gotten filthy rich off Republican tax cuts give back a little bit to a city that is proud of its liberal Democratic values.

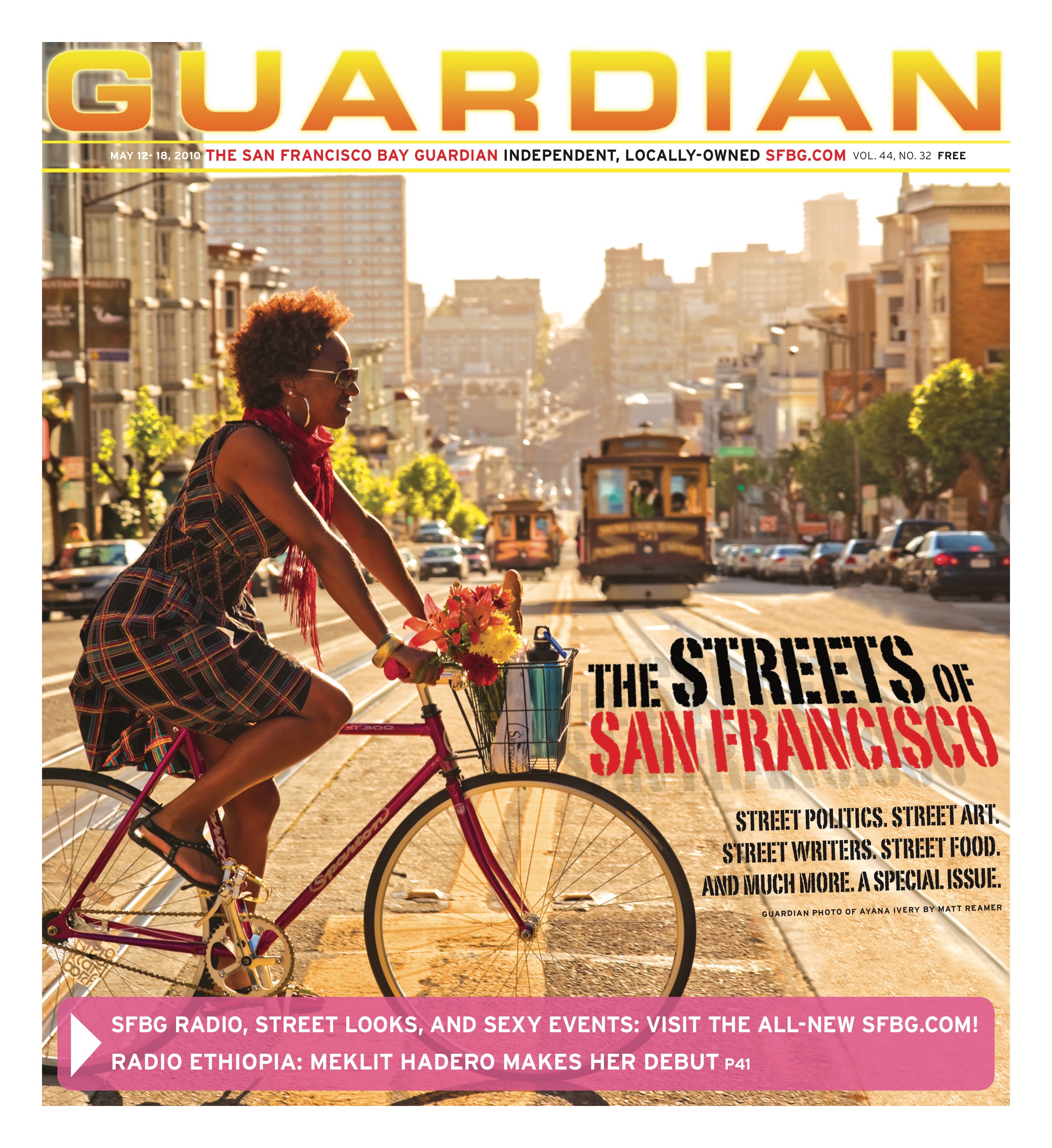

This can be a city where it’s safe to walk and bike on the streets and where clean, reliable buses and trains have priority over cars.

This can be a city where all kids get a good education in public schools.

Despite all the economic woes, this is one of the richest cities in one of the richest countries in the history of human civilization. There are no economic or physical or scientific or structural constraints to reimagining the city. The only obstacles are political.

In the next two years, control of City Hall will change dramatically. Five seats on the Board of Supervisors are up in November, and the mayor’s office is open the year after that. The progressives have made great progress in the past few years — but downtown is gearing up to try to reverse those advances. The community congress needs to address not just the battle ahead, but describe the outcome and explain why San Francisco’s future is worth fighting for.