tredmond@sfbg.com

44th ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL We all arrived in San Francisco broke: Paulo and me in the ’73 Capri, crawling over Donner Pass with a blown valve and three cylinders firing; Tracy and Craig in the back of a VW van, behind in the payments and on the run from the repo men; Tom and Sharon hitching across the Southwest after Tom, who could bullshit with the best, talked himself out a jail cell in New Orleans. Moak showed up in a rusty Datsun with the wheels falling off. Jane and Danny came on the old hippie bus, the Green Tortoise, $69 across the country.

But we all had a friend who knew a friend where you could crash for a little while. And in the early 1980s you got food stamps the first day and it only took a couple of weeks to get a job waiting tables or canvassing or selling trinkets on the Wharf. And once you’d scraped together a couple hundred dollars — maybe two weeks’ work — you could get a place to live. My first room in a flat in the Western Addition was $120 a month.

We did art and politics and writing and music. After a while, some of us went to law school, some of us became journalists, some of us went into government and education. A few of us fled, and Paulo died in the plague (dammit). But in the end, a lot of us were — and are — San Franciscans, part of a city that welcomed us and gave us a chance.

It was a very different time to be young in San Francisco.

I’m not here to get all nostalgic, really I’m not. There were serious problems in 1982 — raging gentrification was creating clashes in the Mission and the Haight and south of Market that were more violent than anything going on today. And frankly, broke as we were, most of my friends were from middle class homes and were college educated and had a leg up. We weren’t going to starve; we didn’t have to make really ugly choices to eat.

Most of the stories in this special anniversary issue are about marginalized youth — young people trying to survive and make their way against all odds in an increasingly hostile city and a bitter, harsh economy.

But there’s an important difference about San Francisco today, something earlier generations of immigrants didn’t face. The cost of housing, always high, has so outstripped the entry-level and nonprofit wage scale that it’s almost impossible for young people to survive in this town — much less have the time to add to its artistic and creative culture.

I met the 21-year-old daughter of a college friend the other day. She’s as idealistic as we all were. She wants to move to San Francisco for the same reasons we did and you did — except maybe she won’t. Because she felt as if she had to come visit first, to use her dad’s network, see if she could line up a job and figure out if her likely earnings would cover the cost of living. When I mentioned that I’d just up and left the East Coast and headed west, planning to figure it out when I got here, she gave me a look that was part amazement and part sadness. You just can’t do that anymore.

The odds are pretty good that San Francisco won’t get her — her talent and energy will go somewhere else, somewhere that’s not so harsh on young people. I wondered, as I do every once in a while when I’m feeling halfway between an angry political writer and an old curmudgeon: would I come to San Francisco today?

Would Harvey Milk? Would Jello Biafra? Would Dave Eggers? Would you?

If you were born here, would you stay?

Are we squandering this city’s greatest resource — its ability to attract and retain creative people?

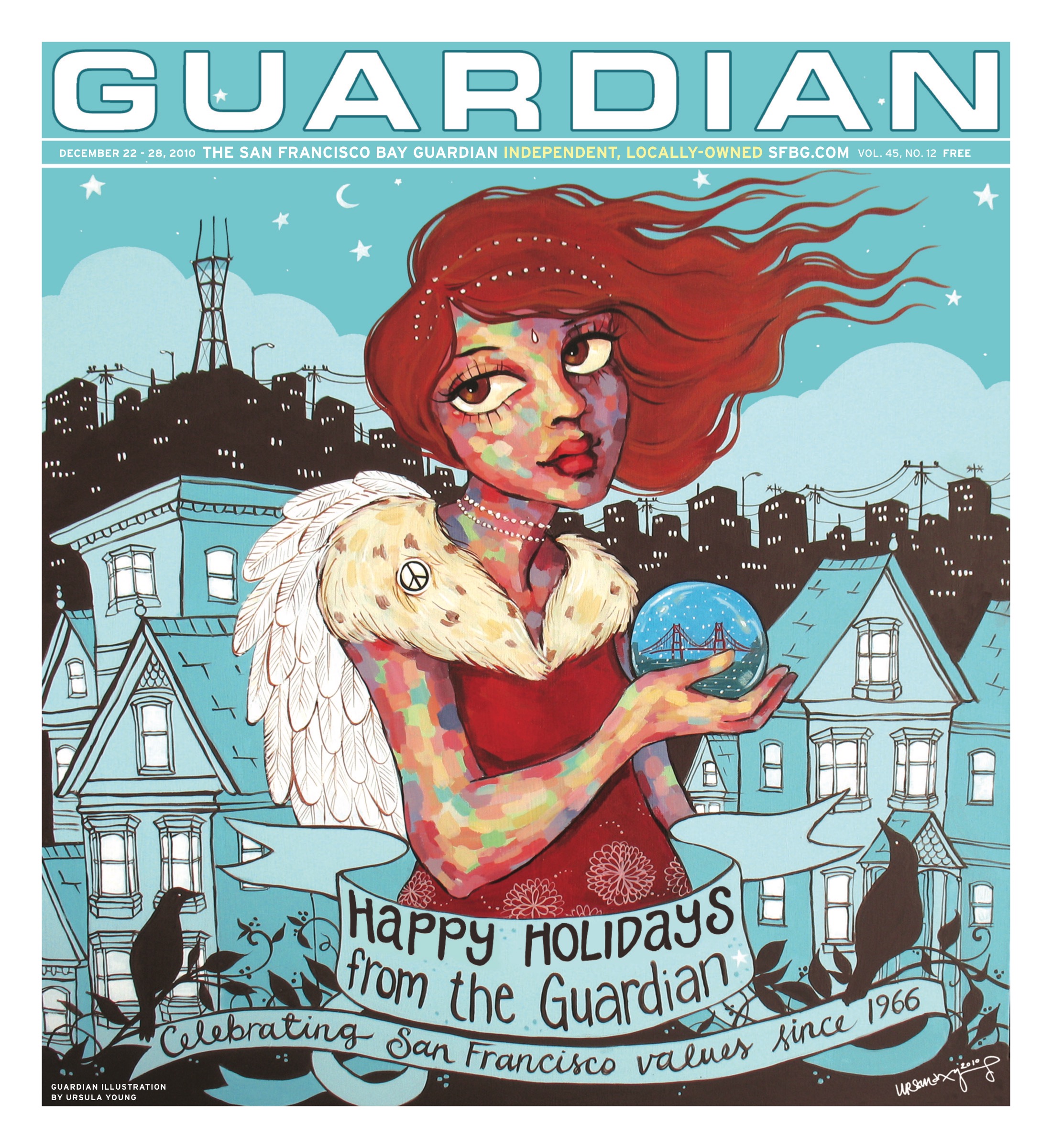

The two people who started the Bay Guardian 44 years ago were young arrivals from the Midwest. Bruce Brugmann looked around the city room at the Milwaukee Journal, where he worked as a reporter, and realized there wasn’t any job he wanted there in 10 years. With two young kids and a dream of starting a weekly newspaper in one of the world’s most exciting cities, Bruce and his wife, Jean Dibble, settled in a $130-a-month flat. The Guardian’s first office was a desk in the printers shop. When they paper could finally afford its own space, Bruce and Jean moved the staff into a $60-a-month four-room place on Ninth and Bryant streets.

From the start, the paper was a “preservationist” publication — both in terms of environmental issues like saving the bay and in the larger political sense. The San Francisco Bay Guardian was out to save San Francisco.

The city was under assault — by the developers who were making fast money tossing high-rises into downtown; the speculators making fast money flipping property, ducking taxes, and driving up rents; the unscrupulous landlords who were letting their buildings fall apart while they charged ever higher rent. For the Guardian, fighting this urbicide meant protecting San Francisco values, preserving the best of the city from what Bruce liked to call “the radicals at the Chamber of Commerce.”

For the Guardian, progress wasn’t measured in the number of new buildings constructed, but in the ability of the city to remain a place where artists and writers and community organizers and hell-raisers — and the young people who were always bringing new life to the city — could survive. We supported rent control, and growth limits, and affordable housing policies, and limits on condo conversions, and minimum-wage and sanctuary city laws — and a long list of other things that together amounted to a progressive agenda.

And in 2010, the assault on the young, the poor, the nonconformists, the immigrants, is still on, at full force. The mayor and his allies are pushing a ballot measure that would make it illegal just to sit on the sidewalk. He’s also turning the local juvenile authorities into immigration cops, breaking up families in the process. He’s cut funding for youth services, and wants to make it easier for speculators to evict tenants, take affordable rental housing (especially the flats that young people share to save money) off the market, and create high-priced condos. Virtually all of the new housing he’s pushing is for rich people. He’s shutting down parties and arresting DJs and, in effect, declaring a War on Fun.

What he’s doing — and what the downtown forces want — is the transformation of San Francisco from a welcoming city where the weird is the normal, where the young and the crazy and the brilliant and the broke can be part of (or even drivers of) the culture, to one where profit and property values are all that matter. And that’s a recipe for urban doom.

Richard Florida’s 2004 bestseller The Rise of the Creative Class shook up political thinking by pointing out that cities thrive with iconoclasts, not organization people. Everyone likes to talk about that now, even Mayor Gavin Newsom. But the missing piece, from a policy perspective, is that the creative class — particularly the young people who are going to be the next generation of the creative class — needs space to grow. And that means the most important thing a creative city can do is nurture the very people Newsom and his allies want to drive away.

If Prop. L, the “sit-lie” law, passes, if the rental flats in the Mission that have been home to several generations of young artists, writers, musicians and future civic leaders vanish in the name of condo conversions, if 85 percent of all the new housing in San Francisco is affordable only to millionaires, if the money that helps foster kids and runaways and at-risk youth dries up because this rich city won’t raise taxes, if nightlife becomes an annoyance to be stifled…then we’re in danger of losing San Francisco.

Our 44th Anniversary Issue also includes stories by Sarah Phelan on SF’s disadvantaged youth, Caitlin Donohue’s account of the Haight street kids, and Rebecca Bowe’s look at ageing out of the foster care system