rebeccab@sfbg.com

Billionaire Sean Parker, the former Facebook president who was portrayed by Justin Timberlake in the film The Social Network, threw a huge bash in late September for Spotify, the digital music platform he’s invested in. The event was held at a Potrero Hill warehouse covered from top to bottom in graffiti to stand out for the occasion, its interior draped with massive, elegant curtains and adorned with chandeliers. The San Francisco Business Times called it “extraordinarily opulent,” with top-shelf booze, pigs roasting on spits, piles of lobster and fresh sushi, and a crowd peppered with celebrities, tech professionals, and venture investors. Former San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown made an appearance at the lavish event, donning a tux.

Parker and Brown have something in common: They’re both supporting Mayor Ed Lee’s bid for a full term in office. While campaign finance law prohibits donors from contributing more than $500 to a candidate running for office in San Francisco, the young tech investor donated $100,000 to an independent expenditure (IE) committee that’s legally separate from his official campaign, called San Franciscans for Jobs and Good Government. Brown, meanwhile, has hosted fundraisers for the mayor and regularly advocates for Lee in his column in the San Francisco Chronicle.

Parker is just one of several billionaires stepping up to support Lee’s mayoral bid. While every mayoral candidate has to raise money, generous support for the interim mayor from the region’s wealthiest figures has raised eyebrows, suggesting that the wealthy and powerful trust him to carry forward an agenda that benefits their interests. Businesspeople with financial stakes in city contracts, real-estate professionals involved in major development projects, and investors in San Francisco companies who stand to benefit from specialized tax breaks can all be found in the mix of Lee’s donor base. Meanwhile, many of the backers who urged Lee to run before he became an official candidate have deep ties to Brown — and several are remembered for coming under the watchful eye of federal investigators when they served as city officials under his administration.

The IE Parker donated $100,000 to was launched by Ron Conway, a prominent tech investor and registered Republican whose net worth also stretches into the billions. Conway, who’s dubbed “The Godfather of Silicon Valley” in a book documenting his meteoric rise, had sunk $151,000 into the committee as of Sept. 24.

Marc Benioff, billionaire CEO of Salesforce.com, dropped another $50,000 into the hat. William H. Draper III, a Silicon Valley venture capitalist who was appointed by Ronald Reagan to preside over the Export-Import Bank of the United States in the 1980s, also pitched in $1,000.

Lee is the city’s first Chinese-American mayor, appointed unanimously by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in January 2011 after his predecessor, Mayor Gavin Newsom, ascended to the Lieutenant Governor post in Sacramento. In the months following his inauguration — when he was still presumed to be a caretaker mayor who would serve only until the end of Newsom’s term — Lee earned praise from his City Hall colleagues for his inclusive style of governance, affable demeanor, and keen understanding of the nuts and bolts of city government stemming from his years of service as City Administrator. He won approval for crafting a city budget by incorporating input from multiple stakeholders, in sharp contrast with Newsom’s tendency to shut out critics.

Lee gave assurances to colleagues and newspaper editors that he wouldn’t run, but changed his mind in early August. Once he threw his hat into the ring, the honeymoon ended — and cash from venture capitalists, tech companies, global engineering firms, and high-end real estate outfits began pouring in.

Collectively, the camp that’s gone to bat for Lee envisions a San Francisco that bears little resemblance to the future progressives have in mind. Where the left advocates more equitable taxation, halting luxury housing construction in favor of affordable residential projects, and creating a municipal bank to free up lending for small business, the mayor’s moderate supporters emphasize propelling forward market-rate development, catering to tech and biotech firms with targeted tax breaks, giving streets a clean and sanitized feel to satisfy tourists, and encouraging more homeownership and less rental housing on the whole.

The rub is that in an evermore expensive city, certain populations — middle-class families, communities of color blunted by unemployment or foreclosure, and creative youth who are cash-poor but dreaming big, for instance — become vulnerable to being priced out. San Francisco is at a crossroads, and the direction it takes will be determined by this race.

SOFT MONEY SUPPORTERS

On the day Lee was inaugurated as mayor, he told a room full of supporters gathered in City Hall’s rotunda, “I was a progressive before progressive was a political faction in this town.” On the campaign trail, Lee’s cited his past work as an attorney for the Asian Law Caucus, describing how he fought to protect tenants and to promote equal opportunity in the San Francisco Fire Department. But that was decades ago — and these days, some heavyweights in Lee’s corner are downright hostile to progressives.

And while Lee does have some progressive support, the bulk of the money behind his campaign comes from people who are on the other side of the political fence — and they clearly think he’s going to listen to them.

Last fall, Conway — the billionaire angel investor who started an IE on Lee’s behalf — told an audience at a business conference that it was time to “take San Francisco back” from progressives. At the time, a polarizing debate was raging over a proposed ordinance that would ban sitting or lying down on city sidewalks, with progressives condemning it as an inhumane anti-homeless measure and advocates trumpeting it as a tool for restoring “civility” to sidewalks. Conway loaned $20,000 to the campaign supporting the law, and the moderates claimed victory.

To improve Lee’s chances of winning, Conway has tapped powerful Sacramento consultants to oversee television spots, polling, and other campaign efforts. The campaign’s law firm, Nielson Merksamer Parrinello Gross & Leoni LLP, teamed up with Pacific Gas & Electric Co. (PG&E) last year to advance a stunningly expensive yet failed ballot initiative designed to crush municipal electricity programs posing a threat to PG&E’s monopoly in Northern California.

Lee drew the ire of a mayoral opponent, City Attorney Dennis Herrera, for remarking that PG&E was “a company that gets it” during a media event; his ill-timed comment came on the heels of a scathing federal report detailing the utility’s culpability for the tragic Sept. 9, 2010 San Bruno gas line explosion.

Another consultant hired by Conway, Aaron McLear of The Ginsberg McLear Group, got his chops on Republican campaign trails, serving as communications director for the 2004 Bush-Cheney campaign in Ohio, and later acting as press secretary to former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. Reached by phone, McLear tried to play down the fact that he was a Republican operative hired by a Republican billionaire to try and influence San Francisco voters to elect Lee. “Yes, I am a registered Republican, but everything we’re spending our money on is Democratic — we’re trying to elect a Democrat in a Democrat town,” he explained, noting that he was also working with Democratic consultant Brian Brokaw.

As part of their efforts, McLear said, the IE had conducted a “virtual precinct walk” developed by a Silicon Valley tech company called Votizen, which utilizes social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook to spread the word about a candidate. Votizen was listed as part of Conway’s investment portfolio in a document published by Business Insider. Zynga and Twitter, two companies benefiting from tax cuts spearheaded by Lee, were also listed in Conway’s portfolio.

Conway’s IE is only one of several that have sprouted up apart from Lee’s official campaign. Another one, the Committee for Effective City Management, drew financial support from city contractors or close affiliates of city vendors. Raymond Lok, who listed his occupation as retired, gave $5,000, while another $5,000 flowed in from 4U Services, a New York based company. A public records search revealed that Lok is related to Melanie Lok, president and CEO of mlok Consulting, who contributed the maximum $500 to Lee’s official mayoral campaign. Melanie Lok listed her occupation as “homemaker” — even though, as the San Francisco Chronicle pointed out, her company holds a contract with the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC) for an invoicing system upgrade worth at least $132,000. (Lok’s odd word choice for her occupation may not be an isolated case. A total of $38,000 flowed into the coffers of Lee’s official campaign from 76 “homemakers,” while another $7,500 was contributed by 15 “housewives.”)

4U Services, which also does business as Stellar Services, holds a city contract for the same SFPUC project that mlok was tapped to work on, worth nearly $92,000. Lok’s consulting firm also does business with Kin Wo Construction, a company that contributed to Lee’s campaign and Brown’s reelection campaign in 1999 — and has been awarded multiple city contracts.

Kin Wo Construction president Florence Kong also contributed $3,000 to Run, Ed, Run. That campaign, which materialized this past spring to encourage Lee to run and drew scrutiny from the city’s Ethics Commission, was driven by Rose Pak, a consultant for the San Francisco Chinatown Chamber of Commerce whose connections with the business world have imbued her with tremendous influence.

And some of the same powers behind the corrupt and anti-progressive Brown administration are Lee backers: Run, Ed, Run accepted $34,715 in contributions from 16 individuals who contributed to Brown’s reelection in 1999, either themselves or through companies they owned, representing about 70 percent of the total contributions.

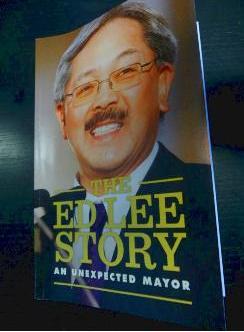

Another IE called the San Francisco Neighbor Alliance , which has yet to reveal its financiers, produced a biography of Lee written by Run, Ed, Run consultant Enrique Pearce and distributed to voters. It’s a violation of election law for an official candidate campaign to coordinate with a third-party committee, but the unauthorized biography contains photographs, anecdotes, and other details of Lee’s personal life that would seem difficult to unearth without the candidate’s help.

Questions surrounding contributions to Lee’s official campaign spurred a criminal investigation by District Attorney George Gascon last week, following Bay Citizen reporter Gerry Shih’s article detailing how airport shuttle drivers were urged by managers to make maximum contributions to Lee in exchange for cash reimbursements. According to a campaign finance document detailing contributions since Sept. 24, just 54 percent of the donors to Lee’s official campaign were San Francisco residents. Among those who made maximum $500 contributions were students, servers, parking garage attendants, cashiers, and a nanny.

Third party committees formed on Lee’s behalf, meanwhile, are working in tandem. On Sept. 16, leaders from all the committees met at the office of Building Owners and Managers (BOMA), an affiliation of San Francisco landlords. “The purpose is to coordinate our efforts, both field and media, to achieve maximum effectiveness,” Alliance for Jobs and Sustainable Growth coordinator Vince Courtney wrote in an email. Recipients included Jim Lazarus and Rob Black of the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce, representatives from the Coalition on Jobs and BOMA, and Rodrigo Santos, a partner in a structural engineering firm called Santos & Urrita which has worked on numerous live/work loft construction projects throughout the city. The email also went to a representative of Left Coast Communications, the outfit that helped steer Run, Ed, Run.

BROWN GOVERNMENT IN EXILE

A San Francisco Chronicle article from 2001 examined the depth of Brown’s patronage politics. “It is well known this town has been for sale since Willie took office,” John DeCastro, president of the Potrero Boosters neighborhood association, was quoted as saying. “Money gets things done.”

And while Lee has a very different political persona than Brown, many of the same people who worked with the former mayor are in the Lee campaign orbit.

“The Ed Lee campaign looks the Willie Brown government in exile, from top to bottom,” Former Sup. Aaron Peskin charged. “Every scurrilous person involved in ripping off the San Francisco taxpayer is neck deep in the Ed Lee campaign. If this guy gets elected mayor, anything that’s not nailed to the floor they’re going to take.”

As the city’s chief executive, Lee comes across as a dedicated public servant who tends to side with the city’s moderates, thrust unexpectedly into the rough and tumble of San Francisco politics. Yet as a candidate, he’s rarely discussed in political circles without mention of his two most visible and influential backers, Brown and Pak. At a mayoral campaign forum in August, Board President David Chiu directed a pointed question at Lee. “So Ed, about a week or two before you told the world that you wanted to — that you were considering — running for mayor, you told me that you had looked at yourself in the mirror, you didn’t have the fire in the belly, you didn’t want to run — but that you were having trouble saying ‘no’ to Willie Brown and Rose Pak,” Chiu said.

A Brown-era City Hall insider told the Guardian that Lee, who previously served as head of the city’s Department of Public Works (DPW) and City Administrator, ascended to his high-ranking posts in part because he was favored by Brown and Pak.

“It was no secret, at least in Room 200, that when Ed was summoned to the office, he got his instructions directly from Willie Brown to do something for someone,” this person recounted. “Willie Brown was smart, he put Ed in positions (Purchaser, DPW) that don’t have commission oversight by charter, and can spend millions. That was not by mistake.”

The statement could be chalked up to mudslinging from any disgruntled foe with an axe to grind, but the wariness of Brown-era politics may stem from past experience. There’s a history of federal investigators looking closely at Brown-appointed city officials for questionable behavior, and several of those former officials turned out at the kickoff for Run, Ed, Run this spring.

Among them was Zula Jones, who worked at the city’s Human Rights Commission (HRC) and was indicted by a grand jury in April 2000 on charges that she allowed a construction company, Scott Co. of San Leandro, to game the city’s minority business certification by creating a false minority-owned contracting company with a Brown donor. The phony front, Scott-Normal Mechanical, Inc., received $64 million in city contracts. According to a 2002 San Francisco Chronicle story, federal investigators found documents they’d subpoenaed next to a paper shredder in Jones’ office — but a judge ruled the evidence was inadmissible, and charges against her were dropped.

In March of 2010, Lee presented Jones with a Community Advocate of the Year award at a banquet hosted by Global Arts and Education to celebrate International Women’s Day. Former Mayor Brown hosted the event.

Another person who turned up at the Run, Ed, Run kickoff was Frank Chiu, who headed up the Department of Building Inspection under Brown’s administration. In 2000, the FBI investigated that department for possible kickbacks and allegedly pressuring permit seekers to use specific contractors. In 2003, the San Francisco Civil Grand Jury issued a report concluding that the department gave “breaks to politically connected developers,” by accelerating approval for their projects.

Also in attendance was Walter Wong, who worked as a consultant to companies seeking project approval from DBI. He came under scrutiny for his cozy relationships with DBI officials, and a 2001 Chronicle article noted that Wong “is often spotted behind the counter before business hours at [DBI], which passes judgment on almost all construction in the city.” The article noted his close ties to Brown and Pak.

In the late 1990s, when Lee served as City Purchaser under Mayor Brown, a company called GSCI was approved as a contractor for DBI even though it was repeatedly rejected by city staff. The company won millions in city contracts, but came under federal investigation for setting up a kickback scheme to defraud the city.

According to the transcript of a deposition carried out by the law firm Gonzalez & Leigh, Deborah Vincent-James — who oversaw contracting for technology companies and has since passed away — testified that GCSI didn’t meet the minimum qualifications (See “Dirty Business,” Feb. 8, 2011). “From day one, I knew that they were not qualified,” Vincent-James’ deposition transcript reads. She went on to say that the official city process for evaluating contractors was “totally bypassed.” Nonetheless, “We had to admit them.” Asked who told her they had to be admitted, she responded, “The director of purchasing. Ed Lee.” She went on to testify that Lee had been acting under the direction of Mayor Brown, who had ties to GCSI principals. When the Guardian contacted Lee for a response to that story, his office did not respond.

Mohammad Nuru, whom Lee recently appointed to lead DPW, was also at the Run, Ed, Run kickoff. He previously served as deputy director of DPW, but drew scrutiny after workers from the San Francisco League of Urban Gardeners (SLUG), a city-funded nonprofit he previously ran, testified that he and SLUG had required them walk precincts and deliver campaign literature for Gavin Newsom for Mayor in 2004 on days they should have been performing street cleaning duties. SLUG was banned from receiving further city contracts following a city attorney’s investigation. Lee says on the campaign trail that he’s going for a full term to continue the tone of civility at City Hall. Yet to longtime observers, his candidacy has come to be defined not by a vision he articulates for San Francisco, but by the past dealings and shady reputations of his supporters. Progressives fear that a Lee administration will be a rehash of the Brown era, with its rampant evictions and favoritism to politically-connected businesses. Lee has voiced his support for inclusivity, smart governance, and fairness, yet some of his greatest boosters seem motivated purely by profit. If Lee wins, his first test will be whether or not he can stand up to the power brokers circling his camp.

Students with deep pockets pony up for Lee

By Christine Deakers

When you talk about students getting involved in politics, you typically think of canvassing, voter registration, and protests. Campaign contributions aren’t anywhere near the top of the list.

In fact, with the bad economy, the soaring cost of education and the crushing burden of student debt, it’s hard to imagine most students having an extra $500 to give to a candidate for mayor of San Francisco.

But nine people identified as “students” gave the maximum $500 to the Ed Lee for Mayor campaign, records show. Two other students, one living in Montana, gave smaller amounts.

Two of those maximum contributions came from young members of the Sangiacomo family, whose senior members have been among the largest and most notorious landlords in San Francisco.

Students Christina and Natalie Sangiacomo both donated $500 dollars. They are the daughters of James Sangiacomo, who helps run Trinity Management Services, a family real estate operation.

Signing a check to Ed Lee seems to be all in the family— the Sangiacomo name appeared 12 times on the donation list, and documented addresses spanned outside of Bay Area zip codes to Corona Del Mar.

We couldn’t reach Christina or Natalie at the family home, but we asked their dad if he knew his daughters gave such substantial amounts to a mayoral campaign. He simply replied, “[Natalie] is 20 and registered to vote.” (For the record, both daughters are over 18, the minimum legal age to make a campaign contribution.)

Hamdiah A. Ahmed (Oakland), Leanna L. Chan (S.F.), Kelly L.L. Chen (S.F.), Stephanie Chen (Danville), Jasmin Perez, Michael Perez (both from Hillsborough), and Yusra M. Sharif (Oakland) also donated $500 to the Ed Lee campaign. Selina Sun (S.F.) donated $250 and Philip O’Connor, on record as a student in Missoula, Montana, gave $175.

Sun’s father, Andrew Sun, is a lobbyist and fundraising consultant at Sun Associates. He gave Lee $100. His wife, Selina’s mother, is Alicia Wang, a long time Democratic Party activist and former candidate for supervisor. Her name did not appear on Ed Lee’s campaign records.

Some students from outside San Francisco kicked in the maximum contribution. Take Hamdiah Ahmed and Yusra Sharif, two unemployed students who live at the same residence in Oakland. The Sharif family owns Oasis Food Market in the East Bay.

There’s no legal reason why a student can’t donate to a campaign — unless someone else provided the money specifically for that purpose. And that’s almost impossible to prove, particularly if a students parents are helping support him or her anyway.

In a phone conversation, Bill Barnes, campaign manager for Ed Lee, emphasized the importance of complying with campaign finance law. He said no one is barred from contributing, and there is “no reason to believe that [students] shouldn’t be helping”.

As for the students who aren’t current San Francisco denizens, Barnes said, “I don’t find it that interesting that second or third generation native San Franciscans feel an obligation to the city.”