steve@sbg.com

It’s hard to keep up with all the changes occurring on the streets of San Francisco, where an evolving view of who and what roadways are for cuts across ideological lines. The car is no longer king, dethroned by buses, bikes, pedestrians, and a movement to reclaim the streets as essential public spaces.

Sure, there are still divisive battles now underway over street space and funding, many centered around the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency, which has more control over the streets than any other local agency, particularly after the passage of Proposition A in 2007 placed all transportation modes under its purview.

Transit riders, environmentalists, and progressive members of the Board of Supervisors are frustrated that Mayor Gavin Newsom and his appointed SFMTA board members have raised Muni fares and slashed service rather than tapping downtown corporations, property owners, and/or car drivers for more revenue.

Board President David Chiu is leading the effort to reject the latest SFMTA budget and its 10 percent Muni service cut, and he and fellow progressive Sups. David Campos, Eric Mar, and Ross Mirkarimi have been working on SFMTA reform measures for the fall ballot, which need to be introduced by May 18.

But as nasty as those fights might get in the coming weeks, they mask a surprising amount of consensus around a new view of streets. “The mayor has made democratizing the streets one of his major initiatives,” Newsom Press Secretary Tony Winnicker told the Guardian.

And it’s true. Newsom has promoted removing cars from the streets for a few hours at a time through Sunday Streets and his “parklets” in parking spaces, for a few weeks or months at a time through Pavement to Parks, and permanently through Market Street traffic diversions and many projects in the city’s Bicycle Plan, which could finally be removed from a four-year court injunction after a hearing next month.

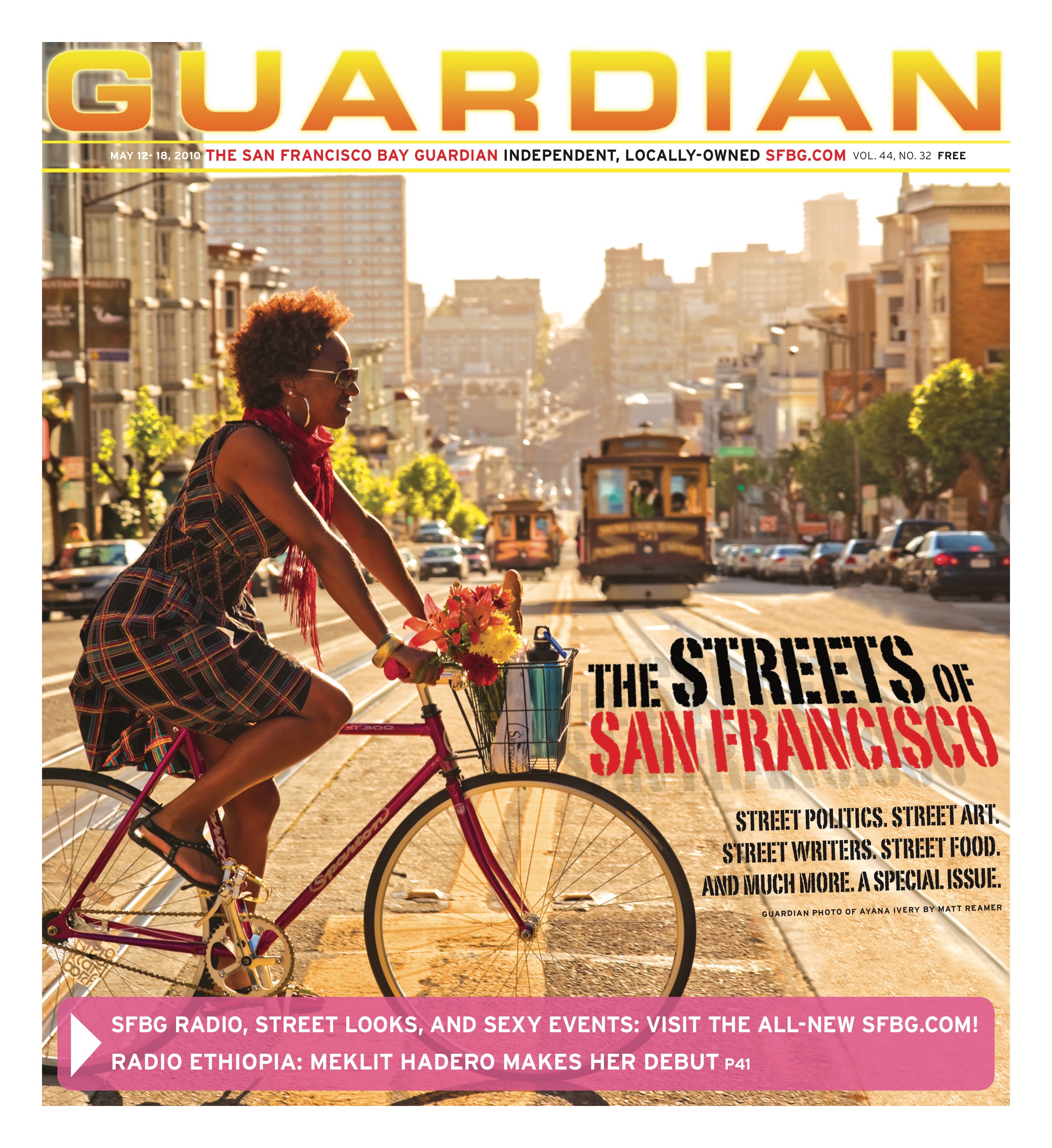

Even after this long ban on new bike projects, San Francisco has seen the number of regular bicycle commuters double in recent years. Bike to Work Day, this year held on May 13, has become like a civic holiday as almost every elected official pedals to work and traffic surveys from the last two years show bikes outnumbering cars on Market Street during the morning commute.

If it wasn’t for the fiscal crisis gripping this and other California cities, this could be a real kumbaya moment for the streets of San Francisco. Instead, it’s something closer to a moment of truth — when we’ll have to decide whether to put our money and political will into “democratizing the streets.”

RECONSIDERING ROADWAYS

After some early clashes between Newsom and progressives on the Board of Supervisors and in the alternative transportation community over a proposal to ban cars from a portion of John F. Kennedy Drive in Golden Gate Park — a polarizing debate that ended in compromise after almost two acrimonious years — there’s been a remarkable harmony over once-controversial changes to the streets.

In fact, the changes have come so fast and furious in the last couple of years that it’s tough to keep track of all the parking spaces turned into miniparks or extended sidewalks, replacement of once-banished benches on Market and other streets, car-free street closures and festivals, and healthy competition with other U.S. cities to offer bike-sharing or other green innovations.

So much is happening in the streets that SF Streetsblog has quickly become a popular, go-to clearinghouse for stories about and discussions of our evolving streets, a role that the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition — itself the largest grassroots group in the city, with more than 11,000 paid members — recently recognized with its Golden Wheel award.

“I think we are at a tipping point. All these little things have been percolating,” said San Francisco Planning Urban Research Association director Gabriel Metcalf, listing examples such as the creative reuse of San Francisco street space by Rebar and other groups (see “Seizing space,” 11/18/09), experiments in New York and other cities to convert traffic lanes to bicycle and pedestrian spaces, a new generation of more forward-thinking traffic engineers and planning professionals working in government, and more aggressive advocacy work by the SFBC, SPUR, and other groups.

“I think it’s all starting to coalesce,” Metcalf said. “Go to 17th and Valencia [streets] and feel what it’s like to have a sidewalk that’s wide enough to be comfortable. Or go ride in the physically separated bike lane on Market Street. Or take your kids to the playground at Hayes Green that used to be a freeway ramp.”

Politically, this is a rare area of almost universal agreement. “This is an issue where this mayor and this board have been very aligned,” Metcalf said. Winnicker, Newsom’s spokesperson, agreed: “The mayor and the board do see this issue very similarly.”

Mirkarimi, a progressive who chairs the Transportation Authority, also agreed that this new way of looking at the streets has been a bright spot in board-mayoral relations. “It is evolving and developing, and that’s a very good thing,” Mirkarimi said.

Both Winnicker and Mirkarimi separately singled out the improvements on Divisidero Street — where the median and sidewalks have been planted with trees and vegetation and some street parking spaces have been turned into designated bicycle parking and outdoor seating — as an example of the new approach.

“It really is a microcosm of an evolving consciousness,” Mirkarimi said of the strip.

Sunday Streets, a series of events when the streets are closed to cars and blossom with life, is an initiative proposed by SFBC and Livable City that has been championed by Newsom and supported by the board as it overcame initial opposition from the business community and some car drivers.

“There is a growing synergy toward connecting the movements that deal with repurposing space that has been used primarily for automobiles,” Sunday Streets coordinator Susan King told us.

Newsom has cast the greening initiatives as simply common sense uses of space and low-cost ways of improving the city. “A lot of what the mayor and the board have disagreements on, some of that is ideological,” Winnicker said. “But streets, parks, medians, and green spaces, they are not ideological.”

Maybe not, but where the rubber is starting to meet the road is on how to fund this shift, particularly when it comes to transit services that aren’t cheap — and to Newsom’s seemingly ideological aversion to new taxes or charges on motorists.

“We’re completely aligned when it comes to the Bike Plan and testing different things as far as our streets, but that all changes with the MTA budget,” said board President David Chiu, who is leading the charge to reject the budget because of its deep Muni service cuts. “Progressives are focused on the plight of everyday people who can’t afford to drive and park a car and have to rely on Muni. So it’s a question of on whose back will you balance the MTA budget.”

WHOSE STREETS?

The MTA governs San Francisco’s streets, from deciding how their space is allocated to who pays for their upkeep. The agency runs Muni, sets and administers parking policies, regulates taxis, approves bicycle-related improvements, and tries to protect pedestrians.

So when the mayoral-appointed MTA Board of Directors last month approved a budget that cuts Muni service by 10 percent without sharing the pain with motorists or pursuing significant new revenue sources — in defiance of pleas by the public and progressive supervisors over the last 18 months — it triggered a real street fight.

The Budget and Finance Committee will begin taking up the MTA budget May 12. And progressive supervisors, frustrated at having to replay this fight for a second year in a row, are pursuing a variety of MTA reforms for the November ballot, which must be submitted by May 18.

“We’re going to have a very serious discussion about MTA reform,” Chiu said, adding, “I expect there to be a very robust discussion about the MTA and balancing that budget on the backs of transit riders.”

Among the reforms being discussed are shared appointments between the mayor and board, greater ability for the board to reject individual initiatives rather than just the whole budget, changes to Muni work rules and compensation, and revenue measures like a local surcharge on vehicle license fees or a downtown transit assessment district.

Last week Chiu met with Newsom on the MTA budget issue and didn’t come away hopeful that there will be a collaborative solution such as last year’s compromise. But Chiu said he and other supervisors were committed to holding the line on Muni service cuts.

“I think the MTA needs to get more creative. We have to make sure the MTA isn’t being used as an ATM with these work orders,” Chiu said, referring to the $65 million the MTA pays to the Police Department and other agencies every year, a figure that steeply increased after 2007. “My hope is that the MTA board does the right thing and rolls back some of these service reductions.”

Transit riders have been universal in condemning the MTA budget. “The budget is irresponsible and dishonest,” said San Francisco Transit Riders Union project director Dave Snyder. “It reveals the hypocrisy in the mayor’s stated environmental commitments. This action will cut public transit permanently and that’s irresponsible.”

But the Mayor’s Office blames declining state funding and says the MTA had no choice. “It’s an economic reality. None of us want service reductions, but show us the money,” Winnicker said.

That’s precisely what the progressive supervisors are trying to do by exploring several revenue measures for the November ballot. But they say Newsom’s lack of leadership on the issue has made that difficult, particularly given the two-third vote requirement.

“There’s been a real failure of leadership by Gavin Newsom,” Mirkarimi said.

Newsom addressed the issue in December as he, Mirkarimi, and other city officials and bicycle advocates helped create the city’s first green “bike box” and honor the partial lifting of the bike injunction, sounding a message of unity on the issue.

“I can say this is the best relationship we’ve had for years with the advocacy community, with the Bicycle Coalition. We’ve begun to strike a nice balance where this is not about cars versus bikes. This is about cars and bikes and pedestrians cohabitating in a different mindset,” Newsom said.

Yet afterward, during an impromptu press conference, Newsom spoke with disdain about those who argued that improving the streets and maintaining Muni service during hard economic times requires money, and Newsom has been the biggest impediment to finding new revenue sources.

“Everyone is just so aggressive on trying to raise revenue. We’ve been increasing the cost of going on Muni the last few years. I think people need to consider that,” Newsom said. “We’ve increased the cost of parking tickets, increased the cost of using a parking meter, and we’ve raised the fares. It’s important to remind people of that. The first answer to every question shouldn’t be, OK, we’re going to tax people more or increase their costs.

“You have to be careful about that,” he continued. “So my answer to your question is two-fold. We’re going to look at revenue, but not necessarily tax increases. We’re going to look at revenue, but not necessarily fine increases. We’re going to look at revenue, but not necessarily parking meter increases. We’re going to look at new strategies.”

Yet that was six months ago, and with the exception of grudgingly agreeing to allow a small pilot program in a few commercial corridors to eliminate free parking in metered spots on Sunday, Newsom still hasn’t proposed any new revenue options.

“The voters aren’t receptive to new taxes now,” Winnicker said last week. Mirkarimi doesn’t necessarily agree, citing polling data showing that voters in San Francisco may be open to the VLF surcharge, if we can muster the same kind of political will we’re applying to other street questions.

“It polls well, even in a climate when taxation scares people,” Mirkarimi said.

BIKING IS BACK

It was almost four years ago that a judge stuck down the San Francisco Bicycle Plan, ruling that it should have been subjected to a full-blown environmental impact report (EIR) and ordering an injunction against any projects in the plan.

That EIR was completed and certified by the city last year, but the same anti-bike duo who originally sued to stop the plan again challenged it as inadequate. The case will finally be heard June 22, with a ruling on lifting the injunction expected within a month.

“The San Francisco Bicycle Plan project eliminates 56 traffic lanes and more than 2,000 parking spaces on city streets,” attorney Mary Miles wrote in her April 23 brief challenging the plan. “According to City’s EIR, the project will cause ‘significant unavoidable impacts’ on traffic, transit, and loading; degrade level of service to unacceptable levels at many major intersections; and cause delays of more than six minutes per street segment to many bus lines. The EIR admits that the “near-term” parts of the project alone will have 89 significant impacts of traffic, transit, and loading but fails to mitigate or offer feasible alternatives to each of these impacts.”

Yet for all that, elected officials in San Francisco are nearly unanimous in their support for the plan, signaling how far San Francisco has come in viewing the streets as more than just conduits for cars.

City officials deny that the bike plan is legally inadequate and they may quibble with a few of the details Miles cites, but they basically agree with her main point. The plan will take away parking spaces and it will slow traffic in some areas. But they also say those are acceptable trade-offs for facilitating safe urban bicycling.

The city’s main overriding consideration is that we must do more to get people out of their cars, for reasons ranging from traffic congestion to global warming. City Attorney’s Office spokesperson Matt Dorsey said that it’s absurd that the state’s main environmental law has been used to hinder progress toward the most environmentally beneficial and efficient transportation option.

“We have to stop solving for cars, and that’s an objective shared by the Board of Supervisors, and other cities, and the mayor as well,” Dorsey said.

Even anti-bike activist Rob Anderson, who brought the lawsuit challenging the bike plan, admits the City Hall has united around this plan to facilitate bicycling even if it means taking space from automobiles, although he believes that it’s a misguided effort.

“It’s a leap of faith they’re making here that this will be good for the city,” Anderson told us. “This is a complicated legal argument, and I don’t think the city has made the case.”

A judge will decide that question following the June 22 hearing. But whatever way that legal case is decided, it’s clear that San Francisco has already changed its view of its streets and other once-marginalized transportation choices like the bicycle.

Even the local business community has benefited from this new sensibility, with bicycle shops thriving around San Francisco and local bike messenger bag companies Timbuk2 and Rickshaw Bags experiencing rapid growth thanks to a doubling of the number of regular bicyclists in recent years.

“That’s who we’re aiming at, people who bike every day and make bikes a central part of their lives,” said Mike Waffenfels, CEO of Timbuk2, which in February moved into a larger location to handle it’s growth. “It’s about a lifestyle.”

For urban planners and advocates, it’s about making the streets of San Francisco work for everyone. As Metcalf said, “People need to be able to get where they’re going without a car.”