joe@sfbg.com

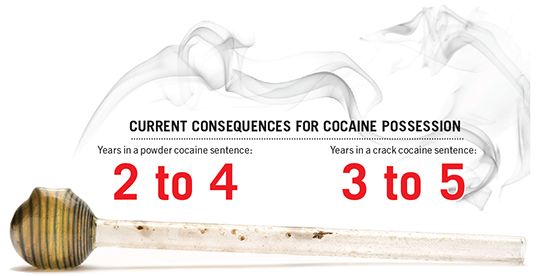

Roll up a dollar bill, snort a line of coke, sit back and smile: If your cocaine use leads to a conviction, your drug of choice will be spared from the harsher penalties associated with inhaling the substance through a glass pipe. When it comes to busts for cocaine possession and dealing, those caught with a rock instead of the powdered stuff are kept behind bars longer. But that could soon change.

The drug is the same, the punishment is not — and a new bill may soon end that decades-long disparity, one that critics have called racist. But crack cocaine use is now at a historic low in San Francisco, raising a question: What took so long?

The California Assembly voted 50-19 Friday [8/16] to pass the Fair Sentencing Act, which aims to lower the sentence for possession with intent to sell crack cocaine to be on par with that of powder cocaine.

The bill, authored by Sen. Holly Mitchell (D-Los Angeles), is seen as championing racial justice.

“The Fair Sentencing Act will take a brick out of the wall of the failed 1980s drug-war era laws that have devastated communities of color, especially black and Latino men,” Lynne Lyman of the Drug Policy Alliance said in a prepared statement.

Crack cocaine rocks have tended to be more heavily used by African Americans, while powdered cocaine tends to be the province of rich white folks. The bill would lessen the maximum sentence for crack cocaine possession with intent to sell to four years, down from five. It would still constitute a felony.

In California, having a drug-related felony on record can prevent the formerly incarcerated from accessing housing assistance and food stamps, further feeding a cycle of poverty. The Fair Sentencing Act now awaits Gov. Jerry Brown’s pen. But some say this disparity should have been addressed some 30 years ago.

The 1980s gave rise to the “crack epidemic” narrative, a supposedly sweeping addiction promulgated by media reports on crack’s outsized harm to pregnant women and newborn babies. But those health impacts are now understood to be on par with tobacco use during pregnancy, rather than the terrifying danger it was presented to be.

Still, the images and narratives from that era were powerful.

In a television news report that aired in the 1980s, an unnaturally tiny baby quivers and shakes on the screen. Then-First Lady Nancy Reagan appears and hammers the point home: “Drugs take away the dream from every child’s heart, and replace it with a nightmare.” Flash forward to the future, and university researchers have produced studies showing that the babies born to crack-using mothers that so frightened the country were simply prematurely born, and went on to lead healthy lives.

True or not, people were outraged. The change in laws happened “virtually overnight,” Public Defender Jeff Adachi told us. Crack cocaine hit San Francisco hard.

Paul Boden, executive director of the Western Regional Advocacy Project, remembers it well. He had just come out of homelessness in the Tenderloin in the ’80s. Just prior to starting as a staffer at Hospitality House, he saw the worst of it.

“People were killing each other over the stupidest shit. It got really violent,” he said. “What crack cocaine did is it divided a community against itself. I never thought I’d get to a point where I missed heroin.”

But, he added, “I do think the advent of crack and the assumption that every black male was doing crack gave the cops carte blanche for all of their racist patterns.”

According to the Drug Policy Alliance, people of color accounted for over 98 percent of men sent to California prisons for possession of crack cocaine for sale. Two-thirds were black, and the rest were Latino.

Long since the days when cops regularly raided the Tenderloin on a hunt for every glass crack pipe, the SFPD is now a somewhat more lenient beast in the drug realm. Drug arrests in the city dropped by 85 percent in the last five years, according to California Department of Justice data. Police Chief Greg Suhr downsized his narcotics unit, shifting to focus on violent crime.

“People that sell drugs belong in jail because they’re preying upon sick people,” Suhr told the Guardian, although he added, “People with a drug problem need to be treated, as it’s a public health issue.”

Suhr said he supports the lower sentencing for crack cocaine to make it on par with powder.

“Cocaine,” he said, “is cocaine.”

District Attorney George Gascon’s office also prosecutes mostly violent and property crimes as opposed to drug possession, reflecting a rare show of agreement between the Public Defender’s Office, the SFPD, and the DA. San Franciscans battling drug problems are often diverted to drug courts and rehabilitation programs.

Crack cocaine has largely moved on from San Francisco, leaving its ugly legacy. Meanwhile, heroin use is on the rise, but nevertheless carries the same harsh sentence as crack cocaine for possession with intent to sell.

“It’s the pathetic state of politics today that it took this long for this to happen,” Boden told us, on sentencing reform. “Now it won’t cost me anything, I’ll show what a great liberal I am.”