steve@sfbg.com

San Francisco has a long history of campaigns to “clean up” its poor neighborhoods, which is often code for displacing low-income residents of color and replacing them with gentrified housing and businesses. It happened in Western Addition and Yerba Buena starting about 50 years ago, and it’s happening now in the mid-Market Street corridor and in the heart of the Mission District.

Clean Up The Plaza is the latest group to decry poor people with bad habits congregating in public places, in this case the 16th and Mission BART plaza. Last summer, it launched a campaign with mailers and window placards that echo its lobbying of city officials to get tough on drug dealing, public urination, robberies, and other crimes.

With more homeless and other people showing up on the street in the Mission District these days, partly because of the increased policing along mid-Market since Twitter and other tech firms moved there in recent years, there are legitimate crime and quality-of-life concerns there, as the district’s Sup. David Campos acknowledges and has been taking steps to address.

“But there’s a difference between focusing on violent crime, as we have on 16th, and criminalizing poor people,” Campos told us. “What we haven’t done is kick poor people out of the plaza or removed benches or anything like that.”

FRONT FOR DEVELOPERS?

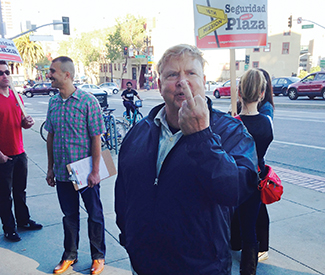

There is more to Clean Up The Plaza than meets the eye, thanks to the secretive involvement of notorious developer-connected political consultant Jack Davis, whose support the Bay Guardian exposed last week. The group’s figurehead, political neophyte Gil Chavez, lives in Davis’ house in the neighborhood and has told Bay Guardian sources that he and others are being well-paid by Davis.

Asked by the Guardian whether he is being paid by the developers — Maximus Real Estate Partners, which has proposed building a 10-story, 351-unit housing project that would tower over the plaza — Davis told us, “That’s between me and the IRS.”

Actually, the Ethics Commission confirmed that it is also looking into the group’s activities given that it hasn’t filed any paperwork in association with political fundraising or its lobbying. Davis denies that the group is in violation of any disclosure laws, and referred questions to high-priced attorney James Perrinello, who hasn’t returned our calls.

Local activists have long suspected this is simply a front group financed by developers to lay the political groundwork for approving the controversial project.

“I wasn’t surprised. I always knew there was some big money behind this,” Laura Guzman, who heads homeless outreach and services for Mission Neighborhood Resource Center, told the Guardian. “This is clearly about displacement. It invoked to me that my guys are in danger.”

“The minute I saw those placards and the flyers with the ‘clean up’ rhetoric, I got nervous because anyone who’s lived in this town for any length of time and paid attention knows exactly what those things mean. The clean up rhetoric almost always means, ‘let’s remove these people,'” said Cleve Jones, a progressive activist who has worked on housing rights issues since the ’70s, when he was a legislative aide to the Sup. Harvey Milk. “What people don’t understand is how completely this is driven by developers, and when you look at who benefits, it’s always the developers…The power of the developers here is enormous and the profits are enormous.”

Housing Right Committee Executive Director Sara Shortt calls Clean Up The Plaza “a fake grassroots campaign that is misleading this community.”

Asked about the group’s relationship with Maximus, Chavez told us, “They’re in communication with us and we’re in communication with them, but they haven’t funded us.” Davis and Chavez say their only motivation in running the group is improving public safety. “I’m happy to talk about what Clean Up The Plaza is,” Davis told us. “I live at 17th and Mission and I’ve been mugged.”

“If you didn’t know Jack Davis’ history in politics in San Francisco, you might be able to take that at face value,” Shortt said of Davis’ claims to be simply a concerned citizen. “Given his ties to big developers, it’s not very believable.”

‘CLEAN UP’ DEFINED

Clean Up The Plaza barely conceals what it’s trying to “clean up,” recently writing to supporters, “A recent BART survey counts about 250 homeless who make daily visits to the plaza. There are 43 SROs in a 4 block radius that add to the plaza population.”

Campos said he’s been working to address bad conditions in some of the Mission SROs, acknowledging that, “You would be hanging out in the plaza too if you didn’t feel safe in your SRO apartment.”

Davis forwarded the Guardian a letter from a local supporter of the group describing to the SFPD his personal crusade against those who hang out in the plaza and urinate outdoors, writing, “There are those of us who ARE LOOKING FORWARD to the new condos and retail space set to be developed at the Plaza. I hope the new retail/condo space helps to improve the area but there are no guarantees.”

But activists call this argument a well-worn ruse used to push development and gentrification.

“Cleaning up so-called ‘blighted’ areas has long been used to push through development projects,” Shortt said, decrying the “false dichotomy” presented by development advocates: “You can walk in puddles of urine or we can save you with a big development project.”

Ironically, the problem has gotten worse in Mission because of previous “clean up” efforts along mid-Market.

“The clean up of mid-Market resulted in more people in the Mission, which nobody is talking about,” Guzman said, noting that the increasing homeless population hasn’t been greeted with increased services, only scorn. “If ‘cleaning up’ really means helping, that’s not helping.”

The mid-Market neighborhoods of the Tenderloin and SoMa and the Mission District neighborhood around 16th and Mission are some of the last places left in the city that are still welcoming of poor people, thanks to the dozens of SROs there, many of them run by nonprofits under city contracts.

The Tenderloin’s 94102 ZIP code has a median household income of just $22,000, while the 16th and Mission’s 94103 ZIP has a median income of $44,000, both significantly less than the citywide median of $74,000, according to data culled by the San Francisco Mayor’s Office of Housing as part of its ambitious push to build 30,000 new homes by 2020.

Yet if “clean up” is really code for displacement, that raises a troubling question for San Francisco: Will there be any neighborhoods left in this gentrifying city that still welcome the poor?

LAST STOPS

Most of those most actively involved in pushing development and “clean up” narratives wouldn’t discuss it with us.

Randy Shaw, whose Tenderloin Housing Clinic administers millions of dollars in city contracts to run SROs in the neighborhood and who was the biggest private sector architect and cheerleader of the tax breaks offered to Twitter and other big tech firms three years ago, said “I’ll pass” when we asked to interview him about his advocacy for “cleaning up” the Tenderloin.

But we did talk with Board of Supervisors President David Chiu, who has parroted some of Clean Up The Plaza’s rhetoric and referred to its petitions during two of his recent debates against Campos for the Assembly District 17 seat.

Chiu told us he heard about Davis’s involvement with the group “a couple months ago,” but that he raised the issue because “my friends in the Mission have alerted me to the crime issues.”

Chiu said there are “several robberies a day” and “more stabbings than any part of the city” in the plaza (actually, the SFPD reports 10 robberies and nine assaults in February) and that “my focus has always been on crime,” both in the Mission in the mid-Market area, where Chiu was one of the leading advocates at City Hall for using tax breaks and increased police presence to “clean up” the area.

“What I think we need to clean up are the violent crimes,” Chiu said, defending his approach of using economic development tools to turn neighborhoods around. “The mid-Market area has been challenged for decades. We needed to do more to revitalize the area.”

But Shortt said that’s just another way private sector profits take priority over human needs and compassion.

“It’s absolutely no coincidence that Twitter moved in and over 60 tenants in that building [1049 Market St.] received eviction notices,” Shortt said. “There is a clear nexus between new construction and rising real estate values.”

That same phenomenon has already transformed the Castro from a welcome enclave for LGBT outsiders into a middle class neighborhood with skyrocketing home prices.

“In a few years, the only thing gay about the Castro will be the flag,” Jones said. “I feel so vulnerable right now. Where do we go? For my generation of gay men, it’s very frightening.”

“‘Clean up’ to us means displacement, increased violence, and increased stress,” Guzman said. “It’s changing completely the character of the city.”

Campos, who opposed the mid-Market tax breaks and has been skeptical of the rhetoric behind them, said he’s long been working to improve the police presence and social services in the plaza.

“We have been working on 16th and Mission for quite some time,” Campos said. “I want to address it in a way that is independent of any developer’s project.”