It’s the age-old dilemma, the stuff of dozens of thrillers and action movies: You’ve captured a guy who knows exactly where a bomb has been planted, and it’s going to explode in 30 minutes and kill thousands of people. Do you bother to read him his Miranda rights and encourage him to speak to an attorney before he answers any questions?

In the movies, no: You shoot him in the knee, or break his fingers one by one, or waterboard him until he talks, and then with seconds to spare, you rappel down the side of a giant building, crash through the glass door, and disarm the bomb. No sweat.

In real life, it’s a bit more tricky — particularly when the suspect, an American citizen, hasn’t even been arrested yet, but can’t go anywhere because he has a bullet hole in his throat.

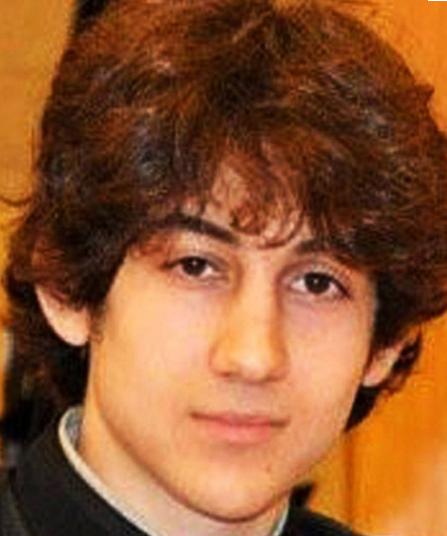

I can get the initial instinct: When FBI agents grabbed 19-year-old Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, they wanted to be sure he didn’t know of any other devices that were about to go off. If they’d refused to read him the Miranda warning and even used “enhanced interrogation techniques” and he’d said: “Hey, OK, I give up, there’s another bomb about to go off,” and they’d found it and saved lives, well…we’d have some Zero Dark Thirty debates, but at least there would have been a point.

In this case, it appears he has said no such thing, and no other bombs connected to him have gone off. There may be evidence that later emerges showing that the normally illegal interrogation saved lives, but so far, it looks as if all the feds have done is compiled information they can try to use against him in court.

Which is a problem.

It’s really, really hard to be even remotely sympathetic here — the guy (allegedly) killed three people, including an eight-year-old, and wounded many more, including a lot of amputations. He terrorized the Boston Marathon. I’m not even remorely suggesting that he get any special treatment. If he’s guilty — and the evidence at this point is pretty solid — then he’s going away for life. (Unless the federal prosecutors foolishly seek the death penalty, which would turn him into a martyr.)

But you can’t just decide that this guy is a bad guy and so the Miranda rule doesn’t matter. There are all sorts of really horrible criminals arrested in the United States, and they all have the right to remain silent, to avoid self-incrimination, and to have an attorney present before they say anything.

There’s a whole cottage industry of cops and prosecutors finding ways to avoid the Miranda warnings, which is not only unConstitutional but somewhat nutty, because Miranda almost never hurts a criminal investigation or prosecution. The Boston Bomber’s case won’t rest on what he told investigators from his hospital bed. In fact, I tend to agree with what law professor David Harris says:

The Obama administration’s interpretation of the public safety exception is suspect; its announcement that no Miranda rights would be given was transparently political, aimed at avoiding criticism from conservative quarters. Worst of all, the administration seemed to be telling the public that Miranda warnings are just petty rules — another instance of hyper-technical laws that get in the way of real justice. This is dead wrong, and it shows grave disrespect for the rule of law and the Constitution — the very things that make our country great.

I would guess that now that Tsarnaev has a lawyer, he’s hearing the grim reality of his situation: Unless there’s something we really don’t know, and he’s got some astonishing claim of innocence, (“my brother made me do it” won’t work) he’s never going to get out of prison, and everything that the legal team does from this point on is about saving his life. He’ll wind up, most likely, pleading guilty to a crime that gives him life without parole, if prosecutors drop the death penalty.

We’ll never know exactly what happened when the FBI gave Tsarnaev a pencil and paper and asked for written answers to interrogation, because that evidence likely won’t be made public. But I suspect that the first thing the agents asked was whether there were any more bombs, and once they got that answer, they should have stopped and issued the Constitutional warnings. Which they almost certainly didn’t.

I know this is speculative, but it’s the reason the Miranda rules are in place. Because we shouldn’t have to speculate on this stuff; we should know that the federal government doesn’t think the “Miranda warnings are just petty rules.”