arts@sfbg.com

VISUAL ART Traveling juggernaut Christian Marclay: The Clock touches down at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art this week for the latest stop along its endless summer tour of major world museums.

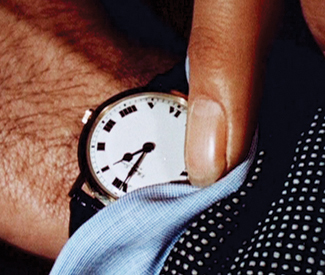

Marclay’s sprawling, oh-shit-inducing video work collages 24 hours worth of clips taken from both obscure and popular films, during each minute of which the correct time is shown on screen. Nominally, the artwork is about the representation of time in film, but it also manages to address some pretty heady concerns, including both the legacy of sweeping Victorian Age attempts to organize every last thing, and also the postmodern, now-seamless interchangeability of simulacrum with reality, making The Clock possibly the perfectly appropriate artwork for the era of Big Data. For the art wonk set, it caps conceptual investigations about indexes and taxonomies that stretch back at least as far as the 1970s, serving as the new-media, zero-degree equivalent of Ad Reinhardt’s all-black paintings. But more than that, it’s something unnervingly similar to Jorge Luis Borges’ fictional map of the world that is the same size as the world, an eerie herald of the age of Orwellian mindfuck as art.

You’re going to see it. Of course you are; it’s the most talked-about work of art since Damien Hirst dropped a preserved shark into a vitrine. But that said, you’re very unlikely to see all of it, unless you do so in May during one of SFMOMA’s scheduled 24-hour viewings.

And if you should give the entire viewing a go, you’ll be participating in what I suspect is the subversive heart of the The Clock, one that makes the entire concept of real time a kind of flimsy absurdism. Actually sitting in the museum in front of a single piece of work for a full day becomes a kind of performance, observing not just the comings and goings on screen, but also in the theater, engaging and disengaging in real life in equal, contesting proportion.

Marclay’s exhibition completes a crescendo at the museum, peaking just before the building closes for expansion, and the exhibits hit the road for various area temporary sites over the next couple years. Together with the current shows dedicated to photographer Garry Winogrand and architect Lebbeus Woods, The Clock is the third in SFMOMA’s trilogy on prolonged, meticulous fascination executed with utmost competence.

And about that Garry Winogrand retrospective, which in its way is even more overwhelming than the Marclay show: the thing you can’t escape while hopping, transfixed, from image to image, is that not only have half of these 300 photographs — many of them stunning — never been shown before, but that it was assembled from a massive archive including some 250,000 images that have never been seen, promising that Winogrand’s posthumous career will stretch on for quite a while.

And good thing, too, since these photographs, while rooted in the mid-late 20th century, are timelessly contemporary. We immediately recognize in them the same mix of unease, willful optimism, and absurdity that mark the post-9/11 world, realizing that disjointedness to be both a continuous thread and defining characteristic of American social fabric.

On the continuum of photographers, Winogrand is somewhere between Weegee’s operatic flair and Walker Evans’ incisive and empathic eye. There are definitely theatrical liberties taken with composition, but at heart Winogrand is a humanist. His particular knack inverts spectacles and intimacies, and his off-kilter shots deliver their actors amid a slippery, complicated search for the American dream.

His famous quote, that “there is nothing as mysterious as a fact clearly described,” speaks to both the allure and the central lie of his (and indeed all) photography. Although he began his career as a photojournalist, his main contribution was visual poetry over raw documentation. The tone of Winogrand’s later work, during which he focused on taking rather than developing or reviewing his photographs, is shot through with distress and disillusionment, as if the world imploded and dissolved completely somewhere around 1977. That late work, long ignored and incompletely catalogued, is featured here, and feels increasingly familiar and prescient.

On the second floor of the museum, the Lebbeus Woods retrospective offers a tonal break from the intense scrutiny of human interaction exhibited by the Marclay and Winogrand shows, but is no less sweeping or meticulous. Woods was a visionary architect of the possible, and although only one of his large scale projects was ever constructed, his psychologically-charged, intellectually-overloaded vision continues to reverberate throughout architecture and design worlds.

The show of 175 works, including models, drawings, and prints, is framed roughly by the Woods quote, “Maybe I can show what could happen if we lived by a different set of rules.” In the Woods universe, those rules bend physics and gravity for the sake of a complete reimagining of human-built structures. Part sci-fi, part utopian thought-experiment, the carefully and expertly drafted renderings of Woods’ theoretical architectural systems are as dizzyingly hypnotic as they are confounding to normal, run-of-the mill concepts of what a building is or should be.

CHRISTIAN MARCLAY: THE CLOCK

April 6-June 2

GARRY WINOGRAND

LEBBEUS WOODS, ARCHITECT

Through June 2

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

151 Third St, SF www.sfmoma.org