arts@sfbg.com

THEATER Tom Cruise, clad in military drag, descended last week by RAF helicopter into Trafalgar Square in what is best described as forced entertainment but was in fact a time-wasting scene from his upcoming blockbuster All You Need Is Kill. Not quite simultaneously but with considerably more stealth, I advanced into South London’s Battersea area, in a completely uncoordinated foray, to see the latest from famed Sheffield-based pomo theater artists Forced Entertainment.

Battersea Arts Centre, a bright red and white 1893 former town hall, is midway through a restoration process called “playgrounding” (putting artists and audiences at the center of the architectural redesign), and its many arches, rococo balustrades, and mosaic tile floors thrive amid an attractive combination of new paint and weathered surfaces. The place is an enviable model for an arts organization: a warm and bustling hub of community activity that is also a serious arts incubator and presenter, boasting 72 performance-tested spaces and a live-in residency program geared to the truly experimental and exceptional.

A nice place for Forced Entertainment to land, enthused artistic director Tim Etchells in a short interview before the evening’s program. He said FE was in fact lucky to find itself there, space in London being at a premium. This is apparently true for even so internationally successful and storied a group as Forced Entertainment.

And speaking of stories, audiences would be up to their ears and eyes in them that night — or rather the loose ends of stories, volleys, and nose-dives from a meta-narrative barrage that manifested itself across a series of readings, performances, and neon. The sign aglow in the Café Bar, where I spoke with Etchells, said simply, “end of story.” Another one said, “Shouting Your Demands from the Rooftop Should Be Considered a Last Resort.”

(All the variously colored neon phrases spread throughout the foyer and adjoining bar were by Etchells, whose many projects outside FE include visual art and writing. The evening kicked off with a book launch of his Vacuum Days, a large hospital-green compendium of daily headlines and announcements — the result of a 2011 internet-based project in which Etchells riffed on the news of the moment in dada-esque fashion. Flipping through the pages was an instant reminder of two things: it had been a hell of a year, and headlines are always loaded.)

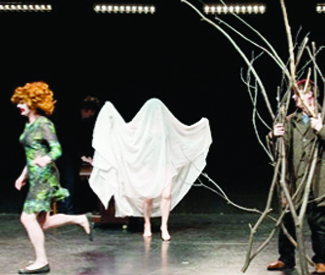

The centerpiece of the evening was The Coming Storm. Forced Entertainment’s latest piece (in an unbroken line of group-devised work going back to the company’s founding in 1984) begins unassumingly, with the six performers in their street clothes lined up onstage facing the audience. One of them holds a microphone, and begins by slowly articulating the necessary ingredients of a “good story.” Soon the other performers grow visibly dubious and restless, until one snatches the microphone away and weighs in with a whopper of a tale, never completed, because also interrupted by another greedy storyteller.

And so on through aggressive, sly, and puerile mic-swipings and gradual, unexpected permutations — as those without the microphone do any manner of things to create their own counter-narratives or merely sabotage the one dominating at the moment. It’s a confluence of fractured accounts arranged like a 20-car pile-up, or a game of keep away, or a gentle dance of despair, with occasional live score, random costume changes, and a cluster of branches embraced (and debunked) as a soothing shelter of forest.

The Coming Storm ends up an exercise in failure and resilience at once, since even if no one completes a tale, the audience rushes to fill the void —our minds trained to shape every squiggle into a recognizable human form, however personal or outlandish the starting point. In that rowdy mutual tangle comes quiet reflection from the interstices of language and history.

It left one in just the right frame of mind to receive the last performance of the night, Sight Is the Sense that Dying People Tend to Lose First, Etchells’ monologue for New York actor Jim Fletcher (lately of the title role in Elevator Repair Service’s acclaimed production, Gatz).

Sight proved no return to narrative but rather a concatenation of eccentric observations and pronouncements, undertaken by a nameless po-faced character standing center stage and meeting the audience’s gaze in a free-associative unburdening of “meaning,” desultory definitions that went along the lines of “Socks are gloves for the feet. Snow is cold. Water is the same thing as ice. In America things are bigger. America is a country. Korea is also a country.” Then, some time later, “Cats are afraid of dogs. Dogs like to chase cats. Some dogs like to bite the tire of a passing car.” Throughout this eccentric cataloguing and its naïve reverie, the audience again acts to complete the work wordlessly. Subtle suggestions come, vistas briefly open, demurring exceptions and musings flicker by, as the audience is tossed one wry bone after another, and a slow vague pathos accumulates.