caitlin@sfbg.com

I couldn’t take my eyes off it. It was gorgeous: a two-way protected bicycle lane. It went the length of Figueroa Alcorta Avenue, a wide, tree-covered boulevard that traverses Buenos Aires’ central neighborhoods. And people were riding bikes on it — cruisers and those funky low-riding foldable bikes. It was a totally different but super-familiar scene. I had to join.

I didn’t come to Buenos Aires expecting to find the bike culture I did. Call me provincial, but the Bay Area bike scene is so exhilarating — the various Bike Party group theme rides, the radical workshops of the East Bay’s Cycles of Change, the gonzo tunes on trailers of the Bicycle Music Festival, SF Bike Coalition’s advocacy work, the slammin’ art and fashion of the Bikes and Beats parties — that it can make a body think we’re taking the whole lane, as it were.

But what else is cruising around out there?

“Buenos Aires does not have any formal complete streets initiatives as the term is understood in the United States,” says Andrés Fingeret, director of the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP). Fingeret’s organization helps cities on three continents — including Jakarta; Guangzhou, China; and Denver — create sustainable transit systems, so I figured the organization would be a good start if I was going to understand where Buenos Aires stands in terms of biking.

“It’s a rare case,” Fingeret continues in an e-mail to me. “A compact city with great weather that is very flat but has no history of urban cycling.”

Following a visit from former Bogotá mayor and bike path champion Enrique Peñalosa, the Buenos Aires city government began working on 100 kilometers of new bike lanes in 2010, many of which are like the one I fell in love with: barrier-protected and luxurious. BA even has Mejor en Bici (“Better on a bike”), a network of free bike rental stations for city residents.

“When these plans were presented, it seemed like a utopia, something that would be impossible in our city,” says Fingeret. “Luckily nowadays, it is debated less and less that bicycles deserve an important role in the mobility of porteños (residents of Buenos Aires).”

But it’s one thing to create bike infrastructure — quite another to get people riding. And despite the city’s ambitious plans, BA has some serious roadblocks when it comes to its population accepting bikes as acceptable forms of transit.

DUMPSTERS IN THE BIKE LANES

A few days after catching sight of that first bike lane, I was on my way to La Bicicleta Naranja (“The Orange Bike”), the Buenos Aires equivalent of SF’s Blazing Saddles bike rental shops. The shop is true to its word — it specializes in renting tangerine-colored cruisers for goober tourists.

Not to retread the path of David Byrne’s Bicycle Diaries too much, but there is something spectacular about seeing a new city from a banana seat. Being a tourist is way more attractive when you can check out multiple neighborhoods in a day, especially in a metropolitan area of 12 million people.

Compared to American cities, traffic in Buenos Aires had a different flow. “Right of way” is a more fluid notion with fewer traffic lights and stop signs but just as many people on the roads — bicyclists, motorists, and pedestrians just have to use their eyes a lot more. Also Buenos Aires appeared to have little emissions level oversight — colectivo buses belched fumes into the streets, discouraging for people commuting without the protection of car walls and windows.

The reality of riding my bike through the city wasn’t quite as paradisiacal as it appeared when standing on the curb — especially given motorists’ ignorance of hand signals (they’re still an uncommon practice among bicyclists there), oblivious pedestrians, and garbage bins parked in delineated bike lanes.

“THE STREETS ARE FOR EVERYBODY”

On a busy street in one of the city’s northern neighborhoods, a year-old bike workshop and skill-share operates out of the back room of a community center. Two days a week, La Fabricicleta is staffed by volunteer bike mechanics who created the workshop after they met through city’s two-year-old Masa Critica (Critical Mass, in one of its many global incarnations), which attracts up to 2,000 riders in the warm summer months and takes to the streets every first Sunday at 4 p.m., with special rides on full-moon nights.

On any given day of operation, the tiny room is packed with mostly young people drinking yerba mate, pumping music, teaching each other how to fix flats and true wheels, and leaving donations for parts and to keep the shop running. It’s similar to SF’s Bike Kitchen — save for its provenance.

Buenos Aires’ neighborhood asambleas were formed in the wake of the country’s 2001 economic collapse, in the midst of runs on the banks, 25 percent unemployment rates, and looting — but also remarkable community organizing. In scenes reminiscent of this spring’s Madrid indignado demonstrations, the city’s plazas filled with demonstrations and entire neighborhoods occupied abandoned buildings, establishing a space where they could try to work through the seismic craziness rocking their country.

Villa Urquiza’s asamblea was one of these — it once housed La Ideal pizzeria, whose sign hangs over the doorway and whose massive ovens still greet visitors. Still buzzing a decade after the crash, the asamblea now hosts political meetings, an anarchist library, occasional fundraiser parties with live music and cheap beer — and La Fabricicleta.

“This is a lifestyle,” says Gustavo Troncoso, one of the workshop’s six core volunteer mechanics. He was introduced to La Fabricicleta through cyclist friends and was impressed by the way people “come to spend the day, and then end up doing mechanics.”

The shop protests throwaway culture, encouraging people to put in the time to resuscitate old bikes. Some of the volunteers who run the shop roll through with decades-old rides restored to impeccably detailed perfection. Another Fabricicleta goal is to provide bikes (and the smarts to maintain them) to low-income riders in the community.

Pausing from helping two young women take their bikes through a routine tuneup, Troncoso explains that riding in the city provides him with some much-needed autonomy from the sardine-packed subway system and environment-polluting car life. “When you get in a car and go somewhere quickly — well you’re not leaving much room for yourself.”

“The streets are for everybody,” he says. “We think everyone can share the same streets with respect. Bikes make you more autonomous, free — you can do it yourself.”

But the social stigma of bikes in Argentina is hard to shake. “Older people still believe that bicycles are for poor people,” says Troncoso, shaking his head. “It’s just a question of education.”

It’s easy to see why La Fabricicleta is packed during its open hours. People come to help out and tune up — but many are there just to kick it. More than a functional service center, the small room is a clubhouse in a town that’s not totally ready for the bike life.

LA VIDA IN BICI

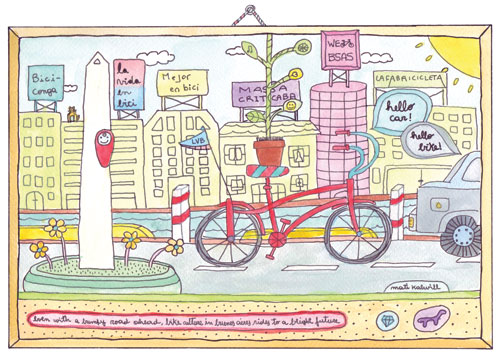

It would be simplistic to say there is a single face of Buenos Aires’ bicicultura (“bicycle culture”). But if you had to choose one, you might select native porteño Matias Kalwill, director of nascent bike culture blog La vida en bici.

Kalwill believes that his city is hitting a “creative boiling point” when it comes to bikes — and other cultural vehicles, for that matter. “Buenos Aires is in a sweet spot,” he tells me over a late night beer. “For example, there’s been new kinds of sounds emerging in the local music scene over the last few years — it’s like a new kind of porteño energy.”

A bicyclist since his high school days who previously worked in a young family education center, Kalwill and friends started Biciconga in October 2010. The group promotes the bike as a part of Buenos Aires’ burgeoning creative culture, not just as a cool toy.

“We wanted to generate bicycle culture by fashion or style. We wanted to make it cool — not just a hippie or sporty thing,” says Felix Busso, one of the group’s founders and a fashion photographer. They began organizing free bike parties, riding en masse to predetermined secret locations where live bands played. The parties took off and in February, Kalwill started La vida en bici.

In the beginning, he used it to share his bike illustrations and videos of various bike happenings. Its popularity grew quickly. Kalwill’s simple view of cycling freedom (“You know how superheroes fly around the city using their own energy? That’s what happens you ride your bike to see a friend across town.”) and anthropomorphic animal characters make bikes seem like something so elementary as to be a common sense part of city living.

The success of the blog and the events Kalwill sponsored through it earned La vida en bici entry into the British Council’s Climate Generation program, a worldwide network that supplies promising young environmental activists with the practical tools needed to make their organizations more effective. Theirs is one of the program’s only bike projects.

I met Kalwill three months after the launch of La vida en bici, at an event he curated at the city’s Museo de Arquitectura y Diseño (The Museum of Architecture and Design). He and the other artists who’d begun working with La vida en bici had been granted use of the museum’s minimalist concrete basement as studio space and had lined it with whimsical bike illustrations, silkscreens, and photographs.

That day, the group was holding its second Bicifriendly event at the museum. On the schedule were art demonstrations, bike maintenance lessons, and a discussion with city experts on the potential of complete streets plans in the city. Kalwill was dashing around in his signature Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou-esque red beanie, playing welcome wagon, docent, and hype man.

“One year ago, none of this existed,” he said. “This idea that the bicycle was cool, that’s really something special. It broke into the culture of the city without permission. And since it didn’t ask permission, it has people asking, ‘Hey, where are you going?'”

But he’s had something to do with this shift in perception. The Biciconga collective and the artists in La vida en bici — rarely older than Kalwill’s 30 years — are experts at packaging the joy of riding a bike in the city into a thousand easily digestible, easily sharable forms — key in the Facebook era. Bicifriendly, although an inspiring moment for those who could make it to the architecture museum, would soon have its impact magnified one-hundredfold by sweetly soundtracked event videos and professional-quality photographs posted onto blogs.

This dispersal is a big part of Kalwill’s plan. “For me, my work is like seeds. Thanks to the Internet, what I do is in part a result of things happening in other countries. And other things will come from what we’re doing here.” He is an avid follower of sites like Streetsblog in New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C., as well as the San Francisco Critical Mass site. He regularly posts bike happenings from around the world on his own websites.

La vida en bici‘s tastemaking ability has also caught the attention of city officials. Paula Bisiau, director of the Palermo neighborhood government, tapped the group to create a “Bicifriendly plaza” featuring a massive mural inspired by Luna de Enfrenta, a book of Jorge Luis Borges poems. In La vida en bici‘s typical cartoonish style, the design will revolve around the question “What would it be like to ride a bike to the moon?”

Bisiau has high hopes for promoting bicicultura projects in her neighborhood. “We hope that these spaces will be starting points to develop more ideas to help foment the use of bicycles in the rest of the city of Buenos Aires,” she wrote to the Guardian. “I think that this change is possible because it’s positive and healthy for everyone. I’m sure that in four more years, we’re going to see many more bicycles in circulation throughout the whole city.”

But it’s not all line drawings and bike music. In the run-up to the July 9 mayoral election, representatives from the office of the city’s current mayor, Mauricio Macri, as well as the two opposition candidates called Kalwill to discuss bike policy in the city.

He chatted with them about what’d he seen in the city — a bit reluctantly. Kalwill is loathe to get involved in politics, wary of the limitations they can impose on cultural movements. But soon afterward the two challengers reversed their previously held viewpoints that the city’s burgeoning bike lane network was a waste of street acreage and resources. Days before the election, everyone could agree that bikes were key to sustainable mobility. “It’s like bicycles won in this election,” reflects Kalwill, who maintains a strictly nonpartisan stance. Between the city’s cultural activists and politicians, he says, “the dialogue is happening.”

At a recent rally, Macri announced plans to build 100 new stations for the city’s Mejor en Bici program. Kalwill was pleased to learn of the plan but does have one bone to pick: at the moment all the free bikes are yellow. He thinks adding different colors to the mix would make the system more attractive to potential bike riders and would “reflect the diversity of the users.”

RUNWAY TO CHANGE

I didn’t bring a bike to the June Masa Critica Buenos Aires ride, and it hurt — I wanted to ride it bad. But my flight back to the States was scheduled to depart in three hours so I stood beneath the massive obelisk that soars from a plaza in the middle of Buenos Aires’ 14-lane 9 de Julio Avenue, the widest street in the world, saying goodbye to my new friends on their two wheels.

But Buenos Aires wasn’t done with me yet — a volcano explosion in the Andes delayed my flight home for three days. As luck would have it, I neatly missed the Biciconga post-Masa bike runway show, where 30 bikers, fresh from the ride, rolled down a makeshift red carpet on the front porch of an organic food co-op to live music by the Mahatma Dandys, a local folk-rock ensemble.

Busso, a driving force behind the show, hoped the spectacle would be a moment that helped change the way Buenos Aires looks at the way it uses bikes. “The more people who use the bicycle, the better. The change will not come from the government, it will come from these groups.”

After biking in Buenos Aires, it seems clear that people in other cities are forming indigenous, exciting bike cultures. But this turn to bicycles is less of a globalized fad as much as water naturally finding its level. In a world where the future of fossil fuels is uncertain and people everywhere are beginning to see the need for a more sustainable lifestyle, urban biking is a matter of common sense.

For Kalwill, the rise of the bike means a better future for his home. “It brings hope that things can change. And we need big changes if we expect to survive in a world that’s getting more crowded and warmer. We need hope. In Buenos Aires, bikes seem to be providing that.”