steve@sfbg.com

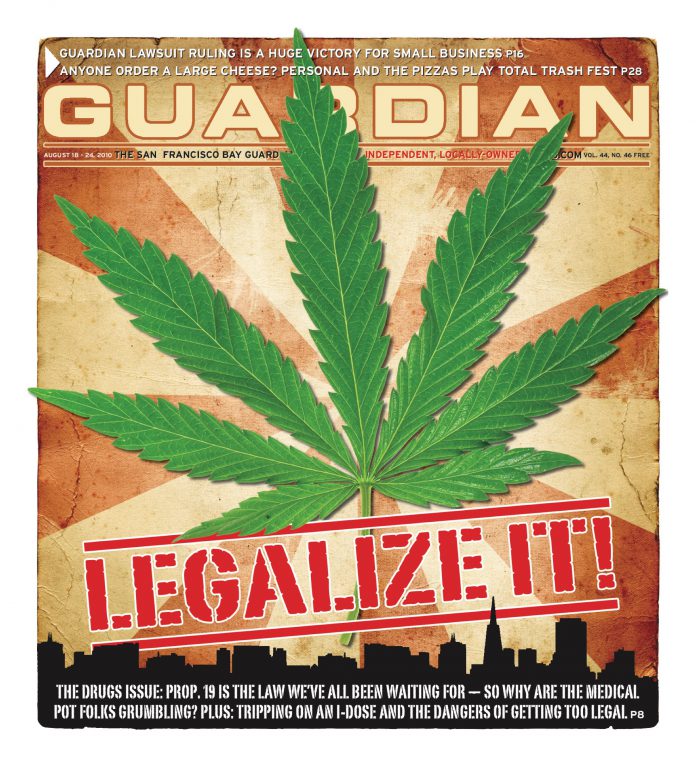

DRUGS With polls showing that California voters are probably poised to approve Proposition 19 in November and finally fully legalize marijuana, this should be a historic moment for jubilant celebration among those who have long argued for an end to the government’s costly war on the state’s biggest cash crop. But instead, many longtime cannabis advocates — particularly those in the medical marijuana business — are voicing only cautious optimism mixed with fear of an uncertain future.

Part of the problem is that things have been going really well for the medical marijuana movement in the Bay Area, particularly since President Barack Obama took office and had the Justice Department stop raiding growing operations in states that legalized cannabis for medical uses, as California did through Proposition 215 in 1996.

In San Francisco, for example, more than two dozen clubs form a well-run, regulated, taxed, and legitimate sector of the business community that has been thriving even through the recession (see “Marijuana goes mainstream,” Jan. 27). The latest addition to that community, San Francisco Patient and Resource Center (SPARC), opened for business on Mission Street on Aug. 13, an architecturally beautiful center that sets a new standard for quality control and customer service.

“This is the culmination of a 10-year dream. We’re going to have a real community center for patients with a great variety of services,” longtime cannabis advocate Michael Aldrich, who cofounded SPARC along with Erich Pearson, told us at the club, which includes certified laboratory testing of all its cannabis and free services through Quan Yin Healing Arts Center and other providers.

Yet cash-strapped government agencies have been hastily seeking more taxes and permitting fees from the booming industry, particularly since the ballot qualification of Prop. 19, an initiative that was written and initially financed by Oaksterdam University founder Richard Lee that would let counties legalize and regulate even recreational uses of marijuana.

Oakland, Berkeley, Richmond, and other California cities have placed measures on the November ballot to tax marijuana sales, and the Oakland City Council last month approved a controversial plan to permit large-scale cannabis-growing operations on industrial land (see “Growing pains,” July 20).

In an increasingly competitive industry, many small growers fear they’ll be put out of business and patient rights will suffer once Prop. 19 passes and counties are free to set varying regulatory and tax systems, concerns that have been aired publicly by advocates ranging from Prop. 15 author Dennis Peron to Kevin Reed, founder of the Green Cross medical marijuana delivery service.

“It’s tearing the medical marijuana movement apart,” Reed told the Guardian. “It’s a little scary that we’re going to go down an uncertain road that may well scare the hell out of mainstream America.” Indeed, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder — who ended the raids on medical marijuana growers — has said the feds may reengage with California if voters legalize recreational weed.

Yet Lee said people shouldn’t get distracted from the measure’s core goal: “The most important thing is to stop the insanity of prohibition.” He expects the same jurisdictions that set up workable systems to deal with medical marijuana to also take the lead in setting rules for other uses of marijuana.

“It will be just like medical marijuana was after [Prop.] 215, when a few cities were doing it, like San Francisco, Oakland, and Berkeley,” Lee told us. “And for cities just coming to grips with medical marijuana, it will be clean-up language that clarifies how they can regulate and tax it.”

Indeed, the tax revenue — estimated to be around $2 billion for the state annually, according to the California Legislative Analyst’s Office — has been the main selling point for the Yes on 19 campaign (whose website is www.taxcannabis.org) and Assembly Member Tom Ammiano, who authored bills to legalize marijuana and has current legislation to set up a state regulatory framework if Prop. 19 passes.

“It makes it more seductive,” Ammiano said of revenue potential from legalized marijuana. “I’ve been working with Betty Yee [who chairs the California Board of Equalization, the state’s main taxing authority] on a template and structure for taxing it.”

Reed and others say they fear taxes at the state and local levels will drive up the price of marijuana, as governments have done with tobacco and alcohol, and hinder access by low-income patients. But Ammiano scoffed at that concern: “Even with the tax structure on booze, there was no diminishing of access to booze.”

Pearson said he believes Prop. 19 will actually help the medical marijuana industry. “Anything that takes the next step toward legalizing recreational use only helps medical cannabis,” he said. Pearson moved to California to grow medical marijuana more than 10 years ago, at a time when the federal government was aggressively trying to crush the nascent industry.

“When you’re packing up and running from the DEA all the time, you’re not thinking about the quality of the medicine. You’re trying to stay out of jail,” Pearson said. “Now, we can be transparent, which is huge.”

Like most dispensaries, SPARC is run as a nonprofit cooperative where most of the growing is done by member-patients. Speaking from his office, with its clear glass walls in SPARC’s back room, Pearson said the Obama election ushered in a new openness in the industry.

“Everything is on the books now, whereas before nothing was on the books because it would be evidence if we got busted … We are allowed to have banks accounts; we’re allowed to use accountants; I can write checks; we can talk to government officials,” Pearson said. “It helps with the public and governments, where they see the transparency, to normalize things.”

He also said Prop. 19 will only further that normalizing of the industry, which ultimately helps patients and growers of medical marijuana. SPARC, for example, gives free marijuana to 40 low-income patients and offers cheap specials for others (opening day, it was an eighth of Big Buddha Cheese for $28) because others are willing to pay $55 for a stinky eighth of OG Kush.

“Our objective here is to bring the cost of cannabis down. We can subsidize the medicine for people who can’t afford it with sales to people who can,” Pearson said, noting that dynamic will get extended further if the legal marketplace is expanded by Prop. 19.

While Pearson strongly supports the measure, he does have some minor concerns about it. “The biggest concern is if local governments muddy the line between medical and nonmedical,” Pearson said, noting that he plans to remain exclusively in medical marijuana and develop better strains, including those with greater CBD content, which doesn’t get users high but helps with neuromuscular diseases and other disorders.

Reed also said he’s concerned that patients who now grow their own and sell their excess to the clubs to support themselves will be hurt if big commercial interests enter the industry. Yet for all his concerns, Reed said he plans to reluctantly vote for Prop. 19 (which he doesn’t believe will pass).

“They’ll get my vote because not having enough yes votes will send the wrong message to law enforcement and politicians [that Californians don’t support legalizing marijuana],” Reed said, noting that would rather see marijuana uniformly legalized nationwide, or at least statewide.

Attorney David Owen, who works with SPARC, said the momentum is now there for the federal government to revisit its approach to marijuana. But in the meantime, he said Prop. 19 has come along at a good time, given the need for more revenue and more legal clarity following the federal stand-down.

And even if the measure isn’t perfect, he said those who have devoted their lives to legalizing marijuana will still vote for it: “A lot of these folks, intellectually and emotionally, will have a hard time voting against Prop. 19.”