Legendary Bay-based rock photographer Jim Marshall, who was featured in a Guardian cover story on March 3, 2010, passed away in his sleep Tuesday night in New York at the age of 74. The people who worked with him on the cover story, Johnny Ray Huston and Mirissa Neff, remember him.

Johnny Ray Huston, writer: When someone dies it’s impossible not to think of the last time you saw them. With Jim Marshall, I wish that last time had been different. Jim had called me in the morning to see if I wanted to meet him at his favorite dinner spot. That night, I arrived about 15 minutes late, finding him alone at a table in the center of the place with a glass of wine. It was noisy, and I had to shout more than usual for Jim to hear what I said. I showed him some crummy digital shots I’d taken of a few Bay Area musicians I’d daydreamed about him really photographing, but he seemed distracted, quieter than usual. When we said goodbye later on the corner by his apartment, I assumed his mind was on the future. He was about to leave on a trip, first going to Texas for the monster that is South by Southwest, and then to New York, for a gallery show of his photography and the release of Match Prints, his latest book, a collaboration with Timothy White.

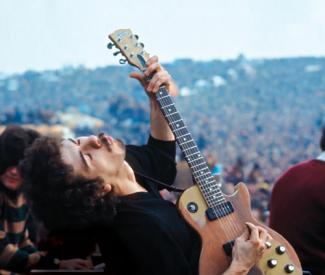

Jim was unfailingly generous. On the day the article I’d written about him was published, he called to say he wanted to give me a print, any print, from his body of work. This kind of offering was second nature for him, but overwhelming for me to contemplate considering the breadth of his vision. At a time when music photography is consumed and tamed by style, all one has to do is look to Jim’s photos for their untamed depth. When my boyfriend Cedar recently interviewed Nancy Wilson, he was amazed to hear her say she had always styled herself for album cover photos. Jim’s peak photos are of true musical artists who had been styling themselves for years. They stepped in front of Jim’s camera without some trite go-between in the way, and with a trust forged by their relationship to him and respect for what he did.

One night after some whiskey at my apartment, I coerced Jim to go to a birthday party for one of my friends, even though it was a Chinese restaurant and Jim hated Chinese food. Jim’s matter-of-fact profanity or vulgarity could be hilarious, as when crab rangoon was placed on the table in front of him and he suspiciously grabbed some, muttering under his breath, “This better not make me puke.” Jim took the tab, even though he had only met the birthday host an hour before. Jim always took the tab.

Jim loved Cadillacs. It was a pleasure to ride with him because of how well he knew his cars. In his newest model, it could also be funny — he didn’t wear a seat belt, so a drive with him meant listening to the incessant ringing of the seat belt alarm coupled with the instructive but useless voice of the GPS. He was blissfully oblivious to both, thanks to deafening encounters with the likes of Jimi Hendrix.

My best friend Corina works at the place where Jim most loved to eat, and while I’m forever grateful to Tim Redmond for encouraging me to meet Jim, I’d first heard about him from her. One Sunday Corina texted me that Jim was at the restaurant and wanted me to come over for drinks after dinner. Corina, Cedar, Corina’s boyfriend Nathan and I all wound up at Jim’s place, as well as a young woman visiting from another country who Jim was romancing when I first got to the restaurant. She had been eating at a different table, but he’d soon gotten her to sit with him. Back at Jim’s apartment, as we talked and drank, the woman put on a CD. It turned out she was a musician, and she wanted us to hear her band. They weren’t bad in an avant-folk 12-piece way, but Jim’s critique of their off-kilter noise was merciless and entertaining. (And it didn’t stop him from getting a kiss from her later.)

When Jim – “Jaguar Jim” back in the Beat era’s heyday – found out that Cedar was a poet with a book due from City Lights, he gave him some rare volumes, including one by David Meltzer. I remember standing on Jim’s front steps that night talking with Nathan about how great the young year was, and how glad I was to be getting to know Jim. At that moment, partly through Corina’s affection for him, I found myself alone with my boyfriend and two best friends in the city, something that wasn’t happening often enough.

Jim had lived in his apartment in the Castro for decades, and he liked to joke that they’d have to wheel him out of it, so it’s one of those deep ironies of life and death that he left this world in New York City. To have met Jim so late in his life is something I can’t fully understand right now. There are so many people I wanted Jim to meet and get to know. But he knew plenty, and many of the best, perhaps better than they could know him. Because of how well he saw them. I feel lucky to have met him, and am grateful he showed me the scrapbook he kept when he was first dreaming about owning a camera. More attention is going to be paid to Jim’s work in the coming months and years. He had a lot of famous admirers, but his day-to-day life in San Francisco was buoyed by people like his friend and assistant Amelia Davis, and Corina and the people at La Med. I can still hear Jim’s pirate-y laugh, and that craggy, lively voice that Corina and I loved to imitate. I can still see his photos.

Mirissa Neff, art director: I met Jim Marshall just a few weeks ago. Our senior arts editor Johnny Ray Huston was interviewing him for the cover story and thought I should meet Jim to go over images, saying “he’d love you.” We all met at his Castro apartment and then walked around the corner to his regular lunch spot, La Mediterranee. For a little guy of 74 Jim had an outsized personality, a gruff demeanor, and a nose that showed signs of his old coke addiction (he was happy to complain to anyone who’d listen that his doctor had made him quit a few years back).

Yet Jim remained completely endearing. As Johnny and I flipped through hundreds of Jim’s stellar portraits, attempting to choose a few images to run (which was no easy task), Jim centered the conversation around an art opening he wanted to attend that night. After describing the event he looked at me and said, “So I’ll pick you up in my Cadillac around 7?” It was less of a question than a directive. I couldn’t make it… which of course I now regret. But being in his presence for that afternoon was a gift.