By Ryan Lattanzio

John Waters. Forefather of filth, pundit of provocation. Not to be mistaken, of course, for 1934 Academy Award recipient John Waters, who kept coming up in my research of the other John Waters.

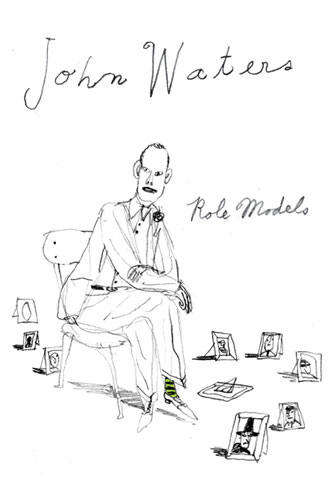

There’s no point in introducing the man, because — well, if you’re reading this, chances are you’re doing so deliberately. No one ever picked up Pink Flamingos by accident and if they did, I’m sorry. His latest book, a collage of candid essays entitled Role Models (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux; 320 pages; $25) is like Hollywood Babylon meets Sodom and Gomorrah. He even tells us, “I know your eyes are not garbage cans, but somehow I feel it is my duty to share with you the depths of depravity some of our long-lost brothers have fallen to.”

Waters is a writer who has seen all tiers of the entertainment industry’s caste system. For him, perversity is pleasure — something to revel in. The titular role models are his own: some are cult figures and pop cultural pariahs, while others are famous figures with whom he’s found inspiration, friendship, and frustration.

There’s little to say on Waters in terms of biography that hasn’t already been said –- the man defines himself. Still, his material is entirely fresh. He remains, and likely always will be, culturally relevant. “I also like Alvin and the Chipmunks better than the Beatles, Jayne Mansfield more than Marilyn Monroe, and, for me, the Three Stooges are way funnier than Charlie Chaplin,” he writes in “The Kindness of Strangers,” an essay on Tennessee Williams.

Waters begins Role Models with a piece on Johnny Mathis, who represents more or less the beginning of what would become his long line of pop cultural idolatry, an ancestry that runs from Rei Kawakubo to NSFW porn auteur Bobby Garcia. “Is it because Johnny Mathis is the polar opposite of me?” he wonders, puzzling over the source of his Mathis fixation. “Do we secretly idolize our imagined opposites, yearning to become the role models for others we know we could never be for ourselves?”

Role Models is eight chapters total, with a few photographs culled from Waters’ grotesque archive. Each chapter is rather long, as he oscillates between discussing the role model in question and discussing himself -– and there’s plenty of the latter. Then again, no one ever looked to John Waters for brevity. In the course of his name-dropping, shit-talking, and first-person autobiographical passages, he places his audience within close emotional proximity. His approach is never didactic. When he comes clean – but when is it ever clean? – it is often shocking and hilarious. No surprise there.

In the flight path of his name-drops, Waters inconspicuously troubles what we know about certain celebrities, and what we’re comfortable knowing. Considering all the people that can be found in his Rolodex, he traffics in some dubious social territory, like his longtime friendship with convicted ex-Charles Manson groupie Leslie Van Houten. His acquaintances also include Little Richard (the progenitor of the pencil-thin moustache!) and pornographer David Hurles, for whom “danger is the turn-on.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QlJDAPlg8rY

Hurles, for one, films “psychos. Nude ones. Money-hungry drug addicts with big dicks. Rage-filled robbers without rubbers. And of course, convicts — his ultimate Prince Charmings.” In Waters’ terms, what would seem like the material for a Hubert Selby, Jr. tragedy or a J.G. Ballard nightmare is actually treated with levity. He makes these misfits, these role models, entirely human — even if their occupations suggest otherwise. Still, the book is rife with freakiness of all shapes and sizes. Waters even recommends Ivy Compton-Burnett as one of his most influential writers.

Waters’ persona is so founded on equal parts artifice and honesty that in deconstructing himself, even the artifice we know and love can be overwhelming. I don’t want the perfectly preserved Waters I imagine in my head to be ruffled. I certainly don’t want to know that his moustache is sometimes penciled on. At this point Waters is such a god-among-gods that the everyday nature of his autobiographical confessions can be jarring.

“I’m so tired of writing ‘Cult Filmmaker’ on my income tax forms,” Waters declares near the close of Role Models. “If only I could write ‘Cult Leader,’ I’d finally be happy.” Such humanizing, humbling moments like these unravel the Waters we normally know to be tethered to a pedestal in the art world. Though he wears his sexuality like a bejeweled blazer, he still defies or subverts gender norms. He’s the prince of filmmaking.

Role Models certainly isn’t the final word on Waters, nor is it the first. This isn’t Waters For Beginners, nor is it Advanced Waters, and anyone will find both comfort and trouble in this book. As an autobiography, Role Models isn’t thorough. But like the Love Map he describes in “Outsider Porn” – an estimate of one’s sexual trajectory spanning their entire lives – this book is a way to trace the path of the artist and really get to the roots. Or maybe it’s more of a palimpsest, something Waters will return to, erase, revise, and rewrite as he gets older. Thankfully, in his case, getting older doesn’t mean maturing.