By Cécile Lepage

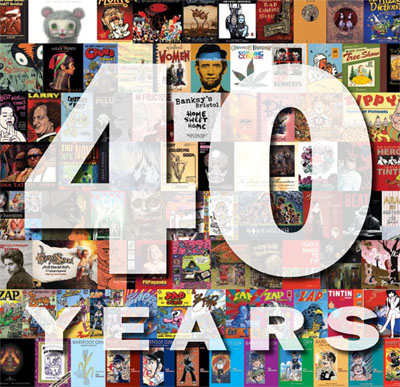

Last Gasp, San Francisco’s landmark independent and underground publisher, is turning 40. To celebrate this feat – in four decades, Last Gasp has spawned more than 300 comics and 250 books – it is throwing a party and an art show Thurs/April 1 at 111 Minna Gallery.

Who dared wager, in the mid-1970s, that Last Gasp would survive the withering of the underground comix scene? Head shops, the main outlet for unedited explicit sex-, drug-, and violence-ridden content (the “x” in comix stands for X-rated), were being prosecuted and forced to shut down due to anti-drug paraphernalia laws. Comics stores favored the more mainstream adventures of masked men in tights. Finally,“there wasn’t the same appetite for comics anymore,” according to Colin Turner, associate publisher to his dad Ron, who founded Last Gasp. No matter: the small venture outlived its peers by continually adapting, tuning to consumer demand and catering to bookstores’ standards and their stapled-leaflet scorn. Over the years, Last Gasp branched out into artist monographs, coloring pads, music-related books and graphic novels.

Yet, browsing its odds-and-ends catalogue, one gets the sense that Last Gasp hasn’t compromised its bizarre and satirical bent. Sure, it might carry such mundane items as coloring books, but beware of the twist! Gangsta Rap Coloring Book flaunts 48-pages of line drawn gangsta rappers. As for Tee Corinne’s Cunt Coloring Book, well, the title says it all. Last Gasp may have diversified, but it never reneged on complete artistic license, the hallmark of underground comix.

Today, Last Gasp thrives in the areas of lowbrow art and pop surrealism. Lowbrow is an umbrella label for “art forms that are popular and wonderful, that people love, but that aren’t respected in the fine art world”, according to Colin. It ranges from tattoos and Kustom Kulture to street art and graffiti – artistic expressions rooted in pop culture that take place on canvases ranging from car exteriors to skin..

As for pop surrealism, the genre emerged from cartoon-y visuals only to reclaim traditional old master painting craftsmanship. Artists such as Scott Musgrove, Camille Rose Garcia and Mark Ryden colonize canvasses with impeccably-rendered phantasmagorical creatures and weird visions. Neglected for years by art institutions, the loose-knit community of lowbrow artists is gradually being endorsed by upscale galleries and museums, a shift that once again attests to Ron Turner’s prescient flair. Back in the day, he promptly discerned underground comix’ wide appeal and cultural relevance, supporting the work of then-young and aspiring artists such as R. Crumb, Bill Griffith, and Spain Rodriguez, all of whom matured into cult or mainstream icons.

It could be said that Ron Turner got sidetracked into publishing. In the late 1960s, the Fresno native enrolled in the SF State psychology department. The Peace Corps volunteer, freshly returned from a stint in Sri Lanka, was thrust into the Bay Area countercultural upheaval and its myriad of grassroots movements. As a Berkeley Ecology Center activist, he figured that he could raise funds by releasing an environmentally-oriented comic book.

“I thought the graphic approach would engage teenagers, help them thwart authority figures, and provide answers to ecological concerns”, Ron recalls. With the mentorship of Gary Arlington, the San Francisco Comic Book Company owner who was selling Zap Comix under the counter, he compiled and printed 20,000 copies of Slow Death Funnies 1. By that time, his Ecology Center accomplices had dispersed, and their successors only agreed to redeem 10 copies of the title. “My garage was filled with 19,990 Slow Death Funnies 1 and I had to find a way to get rid of them”, he laughs.

This task proved easier than one might initially presume: with his good-humored nature, Turner unloaded his goods at 200 locations, not just head shops but also universities, hairdressers and even a leather jacket store. Eventually,Last Gasp reprinted the comic and sold around 45,000 copies. After this initiation, the socially-aware Turner satyed in the business because “it was a kooky way to shed some light on issues that needed attention.”

Last Gasp’s second publication was the all-woman feminist first It Ain’t Me Babe. “At the time, I was living alone with my newly-born daughter and I was drawing comics,” says Trina Robbins, who put together the title. “But you wouldn’t know it, because the 98% male underground comix industry had shut me out. I heard that Ron was looking for material for a women’s liberation comic book. I phoned him. The next day he visited me, wrote me a check for $1,000 — which in those days was quite an amount of money — and voilà!”

The 1975 book Amputee Love probed another rarely addressed topic, the sexual life of a crippled couple. “UC medical centers purchased some copies to sensitize nurses to the fact that amputation does not mean death of sexuality,” says Ron Turner. Other notable contributions to unconventional subject matters include Anarchy (1978) and Cocaine Comix (1976).

According to Ron Turner, cartoonists hold the highest rank in creativity because they can communicate their vision the most clearly: “Most art is some form of propaganda. The artist wants to sell you on his vision and what it leads to.” Turner’s fascination with human behavior conditioning stems from his psychology studies.

At 70, Ron Turner still sports a hippie hairstyle: a white hair ponytail and an eccentric plaited beard running down to the navel of his buddha-like belly. Comix aficionados regard him not only as a pillar but also as a guardian angel. “Last Gasp is unique in that it’s a publishing house and also a distributor. It has kept many smaller and larger presses afloat,” explains Cartoon Art Museum curator Andrew Farago.

Niched in a corner room of Last Gasp’s Florida Street offices, Turner’s personal collection of popular art is an eclectic mix of original drawings and paintings, side show banners, circus items and vinyl sculptures. “Are these for real?”, hollers a guy named Charlie, who is lending a hand in preparing the anniversary art show. He has uncovered a pile of four framed paintings that serial killer John Wayne Gacy made while on death row. Lowbrow art is definitely not for the fainthearted.