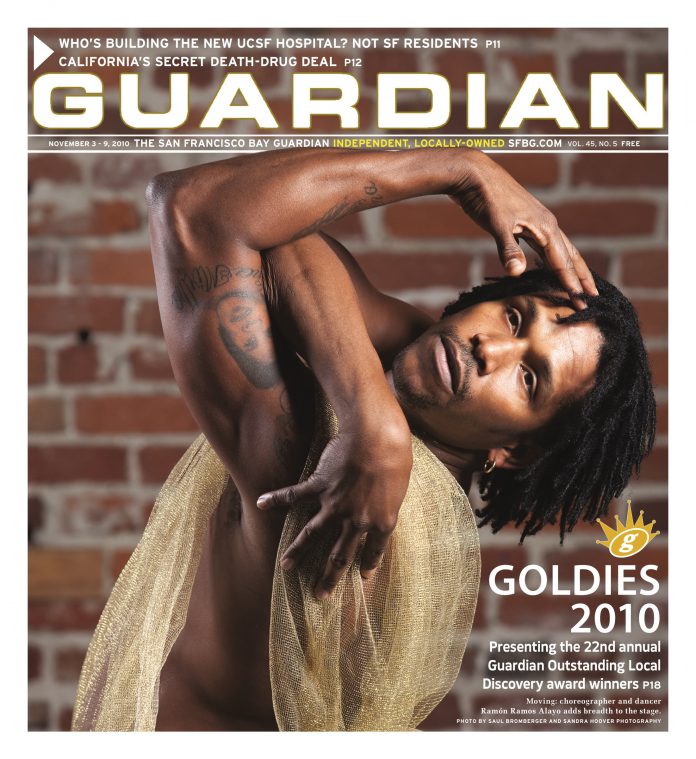

Whoever coined the phrase “jack of all trades, master of none” didn’t foresee an artist like Ramón Ramos Alayo, who is a stunning dancer, a socially committed choreographer, a passionate advocate of Afro-Caribbean culture, scholar of Yoruba spirituality, and an inspiring teacher of modern dance and salsa.

With his tall, powerfully built frame, Ramos Alayo is a mesmerizing presence whether he dances the West African Warrior God Ogun, the Tibetan Lord of Death, the son in La Madre — his tribute to family — or a prisoner trying to shed his shackles. Most recently he assumed Bob Hope’s mantle — unusual even for an open-minded artist like him — by spending a month entertaining American troupes stationed in Europe. “It was a good experience,” the Cuban-born dancer explains. “It was needed. These people have no entertainment. All they do is walk around with guns all day.”

Ramos Alayo regularly returns to Cuba. Next year he’ll go to choreograph and, even more important, to take classes. “The training in Cuba is very strict. There is no choice — you have to go to class,” he says. At 11, he began studying modern and folklórico. He still remembers that unless you met established standards, you couldn’t move to the next level. That kind of discipline paid off. Locally, he has danced with ensembles and choreographers as diverse as Robert Moses’ Kin, Zaccho Dance Theater, Sara Shelton Mann, and Krissy Keefer.

Ramos Alayo has two other passions: choreography and spreading the word about Caribbean culture.

For his Alayo Dance Company, he uses song, music, visuals, and narration to create theatrically potent works that include Afro-Cuban, modern, folkloric, and popular dance styles. Structurally these pieces can be rough, but they have an intoxicating quality — and often a no-holds-barred political perspective — that can prove irresistible. “Mixing things the way he does comes to him by nature and training,” Deborah Valoma, textile artist and costume designer for some of the choreography, explains. “The results are vibrantly alive pieces, approached from an unusually broad set of disciplines.”

After Rain looks at destruction and regeneration from an individual and social perspective. Blood and Sugar traces the passage of slavery through history and geography. A Piece of White Cloth metaphorically explores the movement of culture from Africa via Cuba to the Bay Area. These are big-themed endeavors, but Ramos Alayo also embraces athletic intimacy in works such as Wrong Way and last year’s Grace Notes. Still, Keefer, who first met Ramos Alayo when she took over Dance Mission Theater in 1999, appreciates him above all as a storyteller. “There are so few choreographers in modern dance who create narratives,” she explains.

The Cuba Caribe Festival, which Ramos Alayo founded in 2003, has become a mini ethnic dance festival, showcasing groups from the Cuban diaspora on the first weekend and Ramos Alayo’s ensemble on the second. The festival is always a rollicking, joyous affair. If sometimes there is a friendly rivalry between ensembles, it’s all in good spirit.

In the past, most of Cuba Caribe’s participating groups have been grounded in folklórico traditions. Lately, however, reflecting both the changes taking place within that community and Ramos Alayo’s personal interests, modern dance groups like Paco Gomes and Dancers and Liberation Dance Theater have made successful appearances. Master classes, workshops, and lectures augment the offerings.

Just how successfully Ramos Alayo will be in helping the Caribbean diaspora deepen its roots in the Bay Area remains to be seen. He has two daughters. “One of them is a dancer, the other a soccer player.”