tredmond@sfbg.com

It’s going to take longer, sometimes, to get from here to there. Acres of urban space are going to have to change form. Grocery shopping will be different. Streets may have to be torn up and redirected. The rules for the development of as many as 100,000 new housing units in San Francisco will have to be rewritten.

That’s the only way this city — and cities across the country — can meet the climate-change goals that just about everyone agrees are necessary.

Jason Henderson, a geography professor at San Francisco State University, lays out that case in a new book. He argues, persuasively, that the era of easy “automobility” — a time when people could just assume the ease and convenience of owning and using a private car as a primary means of transportation — has come to an end.

Henderson isn’t suggesting that all private vehicles go away; there are places where cars and trucks will remain the only way to move people and supplies around. But in the urban and suburban areas where most Americans live, the automobile as the default option simply has to end.

“In 10 years, there will be less automobility,” he told me in a recent interview. “It’s a simple limit to resources.”

And the sooner San Francisco starts preparing for that, the better off the city and its residents are going to be.

BIG NUMBERS

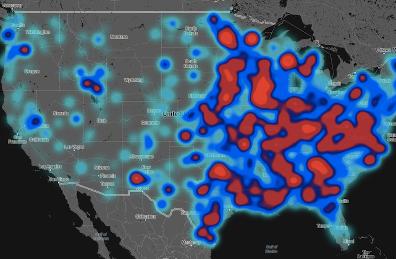

Henderson’s book, Street Fight: The Politics of Mobility in San Francisco, focuses largely on the Bay Area. But as he points out, the lessons apply all over. The numbers are daunting: Cities, Henderson reports, “use 75 percent of the world’s energy and produce 78 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions.” He adds: “Transportation is the fastest growing sector of energy use and [greenhouse gas] emissions, and this fact is in great measure owing to the expansion of automobility.”

And the United States is the biggest culprit. This nation has 4 percent of the world’s population — and 21 percent of the world’s cars.

To turn around the devastating impacts of climate change, “America will need not only to provide leadership, but also to decrease its appetite for excessive, on demand, high-speed automobility.”

And buying a lot of Priuses, or even electric cars, isn’t going to do the job. “Americans must undertake a considerable restructuring of how they organize cities, and that must include the rethinking of mobility and the allocation of street space.”

The Bay Area is about to enter into a long-term planning cycle that, according to groups like the Association of Bay Area Governments, will involve increased urban density. ABAG, according to its most recent projections, would like to see some 90,000 new housing units in San Francisco.

That’s got plenty of problems — particularly the likelihood of the displacement of existing residents. Henderson agrees that more density is going to be needed in the Bay Area — but he’s surprisingly bullish on the much-denigrated suburb.

“It’s actually quick and easy to retrofit suburbia,” he told me.

And like so much of what he discusses in his book, the primary solution is the old, venerable, human-powered contraption known as the bicycle.

“Existing communities like Walnut Creek are eminently bikeable,” Henderson told me. He suggests expanding development in three-mile circles around BART stations — after getting rid of all the parking. “We could easily get 20 to 30 percent of the trips by bike,” he noted.

In fact, he argues, it’s easier to put bicycle lanes and paths in the suburbs than in San Francisco. The streets tend to be wider, there’s more room in general — and it’s fairly simple to provide barriers from cars that make biking safe for everyone.

In fact, a lot of European cities are less dense than San Francisco — and have far fewer drivers. Even in California, the city of Davis is famous for its bike culture; “In Davis,” Henderson said, “There are all these children riding their bikes to school.”

ACRES OF PARKING

One of the most profound changes San Francisco is going to have to make involves coming to terms with the immense amount of scarce space that’s devoted to cars. Parking spaces may not seem that big — but when you combine the 300-square-foot typical space (larger than many bedrooms and offices) with the space needed for getting into and out of that space, it adds up.

“Parking for 130 cars amounts to about an acre, and the aggregate of all non-residential off-street parking is estimated to be equal in area to several New England states.”

Cars need more than a home parking space — they need someplace to park when they’re used. So in a city like San Francisco that has more than 350,000 cars, a vast amount of urban land must be devoted to parking. In fact, Henderson estimates that parking space in San Francisco amounts to about 79.4 million square feet — or about 79,400 two-bedroom apartments. Off-street parking alone takes up space that could house 67,000 two-bedroom units.

And it’s hella expensive. Building parking adds as much as 20 percent to the cost of a housing unit. He cites studies showing that 20 percent more San Franciscans could afford to buy a condo unit if it didn’t include parking.

But the city still mandates off-street parking for all new residential construction — and while activists have managed to get the amount reduced from a minimum of one parking space per unit to a maximum of around eight spaces per 10 units, that’s still a whole lot of parking.

And if San Francisco is expected to absorb 90,000 more housing units, under current rules that’s 72,000 more cars — which means a demand for 72,000 more parking spaces near offices, shopping districts, and parks. Crazy.

So how do you get Americans, even San Franciscans, to give up what Henderson calls the “sense of entitlement that we can speed across town in a private car?” Some of it requires the classic planning measures of discouraging or banning parking in new development (AT&T Park works quite well as a facility that is primarily accessed by foot and transit). Some of it means putting in the resources to improve public transit.

And a lot of it involves shifting transportation modes to walking and bicycles.

San Francisco has had significant success increasing the use of bikes in the past few years. But there are limits to what you can do by tinkering around the edges, with a few more bike lanes here and there.

There are, for example, the hills. And there’s grocery shopping for a family. Those things need bigger shifts in the use of urban space.

San Francisco’s street grid, for example, sends travelers straight up some nearly impossible inclines. Young, healthy people in great physical condition can ride bikes up those hills, but children and older people simply can’t.

Henderson suggests that the city could install lifts in some areas, but there’s another, more radical (but less energy-intensive) solution: Reroute the grid.

If city streets wound around the sides of hills, instead of heading straight up, walking and biking would be far easier. That would involve major changes, particularly since there’s housing in the way of any real route changes — but in the long term, that sort of concept should, at least, be on the table.

Bikes with cargo trailers make a lot of sense for shopping, Henderson told me — and once big supermarkets get rid of all that parking, the price of food will come down.

THE POLITICS OF NEO-LIBERALS

The biggest challenge, though — and the heart of Henderson’s book — is political. Transportation, he argues, is inherently ideological: “It matters how you get from here to there.” And he notes that progressives, who are willing to think about social responsibility, not just individual rights, see the choices very differently than the neo-liberals, who in this city are often called “moderates.” If the neo-libs have their way, he says, the changes will be too little, too late, and mostly ineffective.

Because Americans are facing a series of choices — and there are no solutions that preserve the old way of life without sacrificing the future of the planet. It’s entirely a zero-sum game: We can slow global climate change, or we can keep driving cars. (Oh, and electric cars — which still require large amounts of power, mostly from fossil-fuel plants — aren’t going to solve the problem any time soon.)

We can shift to bicycles and transit as our primary ways to get around, or we can leave our kids an ecological disaster of unprecedented scope. We can overhaul the entire way we think about urban planning — to make streets friendly to bikes and buses — or we can go down a deadly path of no return.

We can accept the fact that moving around cities may be a little slower, particularly while we adapt. Or we can join the climate-change deniers. “There are a lot of neo-liberals out there who say we can’t start controlling automobility until we have a gold-plated transit system,” Henderson told me. “But this is not a chicken and egg problem. First you have to create the urban space. Then you can build a better system.”