It’s true that San Francisco doesn’t really have seasons, per se. We don’t have a snow thaw, or a sudden riot of cherry blossoms, or even a perceptible change in the weather to mark calendar shifts. So grab that lightweight jacket you’ve been wearing since October, and use our selective guide to what music shows to see (dude … Sparks is coming!), gallery and museum shows to hit up, films to catch, and can’t-miss theater and dance performances — including, yep, a fresh take on The Rite of Spring.

MUSIC: SOUL, SPARKS, AND SEVENTIES LEGENDS

“Soul Clap and Dance-Off” (March 30, Rickshaw Stop, SF) After a freak accident in late 2011 (a car plowed into his hotel room), revered New York Night Train DJ Jonathan Toubin is back with his feverish ’60s soul freak out party. The winner of the dance-off gets 100 bones, the guest selector is DJ Primo, and full disclosure, I’m one of the contest judges this time around. www.rickshawstop.com

“Rock See! A Benefit Concert for the Roxie Theater” (April 5, Verdi Club, SF) Support the Roxie by taking in a fundraiser show that’s bursting with local talent, including live sets by John Dwyer’s garage rock superstars Thee Oh Sees, Sonny and the Sunsets, Future Twin, and Assateauge, along with video projections by Barry Jenkins, Jim Granato, and more. www.roxie.com

Sparks (April 9-10, The Chapel, SF) Influential new wave-glam pop duo Sparks hits SF the weekend before Coachella for two intimate concerts, pulling experimental cuts from its 20-plus back catalog of music insider-worshiped albums. www.thechapelsf.com

“CubaCaribe Festival” (April 12-14, Dance Mission Theater, SF; April 19, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, SF; April 26-28, Laney College Theater, Oakl.) The ninth CubaCaribe Festival offers music and dance performances, lectures, and master classes all based in rich Caribbean traditions. Check out Afro-Cuban modern dance company Teatro de la Danza del Caribe’s first US appearance, Brazilian inspired music and dance company Sambaxé, a lecture by popular local percussionist John Santos, and plenty more. www.cubacaribe.org

Lou Reed (April 14, Warfield, SF) Legendary Velvet Underground songwriter and pioneering solo artist in his own right, Lou “Walk on the Wild Side” Reed pays SF a visit, with memories of his contentious collaboration with Metallica on the Lulu (2011) album (thankfully) fading into the past. www.thewarfieldtheatre.com

Savages (April 18, Independent, SF) When all-female British post-punk group Savages hit the East Coast last year for the annual CMJ conference, the word spread quickly to the West: this blistering quartet is one to watch. All these anxious months later, this headlining show will be Savages’ first SF appearance. www.theindependentsf.com

Big Boi (May 16, Mezzanine, SF) After a disastrous non-set at Outside Lands a few years back (DJ technical issues), rapper-producer Big Boi, a.k.a. one-half of Outkast, returned triumphantly in 2012 with an explosive, quick-tongued performance. Now’s your chance to catch him in a far smaller space in 2013. www.mezzaninesf.com

Fleetwood Mac (May 22, HP Pavilion, San Jose) It’s been 35 years since the release of Rumours. Sure, you can go your own way, but never forget how you got there: after years of touring as solo artists, that classic Fleetwood Mac dynamic (everyone but Christine McVie) is back together, or at least, on tour this spring. (Emily Savage)

VISUAL ART: MUSEUMS

“Lebbeus Woods, Architect” and “Garry Winogrand” (Both through June 2 at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) Both are getting lots of attention. Postmodern architect Woods, who just passed away, gets the full retrospective treatment; documentary-style photographer Winograd hasn’t had a retrospective in a couple decades. www.sfmoma.org

“Revisiting the South: Richard Misrach’s Cancer Alley” (March 27-June 16 at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University) Misrach is known for his pristine photographs of blasted and abused environments. The juxtaposition is usually pretty jarring, and I’m a big fan. museum.stanford.edu

“Richard Diebenkorn” (June 22-Sept. 29 at the de Young Museum) New show focusing on abstract paintings from his Berkeley period. deyoung.famsf.org (Matt Fisher)

VISUAL ART: GALLERIES

“Teo González: Recent Paintings” (Through April 20 at Brian Gross) González makes intricate, fastidious paintings, which isn’t such a novelty anymore, except that his match process with subject matter better than most. The show at Brian Gross promises to feature González’s night sky paintings, applying his signature miniscule brushwork to themes of transcendence and chaos. www.briangrossfineart.com

“Evan Nesbit: Light Farming/Heavy Gardening” (March 23-April 26 at Ever Gold) I’m recommending this one based on the overall strength of Ever Gold’s program, which I think it one of the most adventurous in the city — and the fact that Nesbit as an alum of the Yale painting program, which is almost certainly the best in the country. His paintings incorporate real-world woven knits (reminiscent of seat covers, crocheted things, those puffy drawer linings) as the substrate for abstract paintings that manage to combine grid painting, color field painting, and a soft kind of blunt expressionism. www.evergoldgallery.com

“John Millei: Recent Paintings” (March 28-May 11 at George Lawson) Millei is one of Los Angeles’ most virtuosic abstract painters; he usually composes heroic-scaled paintings and projects. His most recent body of work shown at LA’s ACE was from a decade-long project of 200-plus small paintings based on Giotto and Giorgio Morandi. When Millei does historical references, it’s not in the appropriative way that many do, copping motifs and moody lighting effects — it’s in methodically and microscopically breaking down both image and process to reestablish both the image’s dynamic and the role of the artist. For George Lawson, he’s making new works for the tiny Tenderloin space. For my money, Millei is one of the most romantic of living abstractionists. www.georgelawsongallery.com (Fisher)

DANCE: PREMIERES WITH MUSIC, PREMIERES WITH PLANTS

Mago (April 12-14, CounterPULSE) Dohee Lee is that rare creature steeped by inclination and training in a traditional culture — but who is also a completely contemporary artist. She is a singer, a dancer, and a Korean-style Taiko drummer. But she also knows how to weave these abilities into storytelling and ritualized theatrical creations. For Mago, her exploration of the Korean goddess associated with the creation and care of the earth, she adds animation and custom-made instruments to her skills box; it’s a work that integrates her theatrical practice with ritual and Korean shamanism. www.counterpulse.org

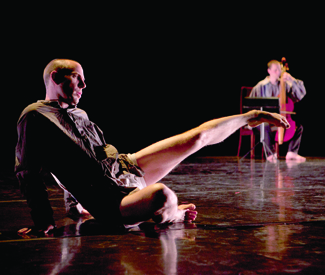

Failure of the Sign is the Sign (May 3-5, ODC Theater) The sixth season of Hope Mohr Dance continues what Mohr does so very well: presenting her own very smart choreography but also, through her Bridge Project, bringing in colleagues whose work she admires. This year, it’s Alpert Awards winner Susan Rethorst with the West Coast premiere of her intricate and much-praised Behold Bold Sam Dog. Mohr’s own new work, Failure of the Sign is the Sign, is an installation around the connection between acquiring language and a sense of self. www.odcdance.org

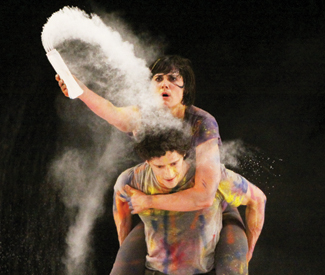

“Ojai North 2013” (June 12-15, Hertz Hall, UC Berkeley) The world premiere of Mark Morris’ Rite of Spring just might be the season’s hottest ticket. In many ways it’s an outrageous idea to rework one of the most famous 20th century scores for piano, bass, drums. Bu that’s exactly what the three jazz musicians of the Bad Plus did. Never mind that 100 years ago at its world premiere, Stravinsky had an orchestra of 110 musicians — not including strings — at his disposal. Morris, a musically sophisticated choreographer, apparently loved it, and is setting it on his Mark Morris Dance Group. He’s been choreographing for over 30 years, and he still manages to surprise us. calperfs.berkeley.edu

Botany’s Breath (July 10-13, Conservatory of Flowers, Golden Gate Park) For Botany’s Breath, Kim Epifano works with nine professional dancers as well as a dozen community performers. The piece honors the natural world in dance, music, song, and video and pays tribute to the historically significant Conservatory of Flowers. Collaborating with her are instrument builder Peter Whitehead, musician Norman Rutherford, and videographer Ellen Bromberg. You can expect the show to spill out of the quaint Victorian structure into the surrounding environment. www.epiphanydance.org (Rita Felciano)

FILM: FESTIVALS, REP HOUSES … AND A GIANT-ROBOT FLICK

With Hollywood committed to an array of sequels, prequels, and do-overs (like, how many hangovers, Spocks, fast/furious drivers, Supermen, Iron Men, Wolverines, and Gatsbys do we need, really?), your best bet is to focus on film festivals and rep houses this summer. (Maybe take time out for Guillermo del Toro’s aliens vs. giant robots epic Pacific Rim, due July 12 — now that seems worthy of massive popcorn consumption.)

San Francisco’s spring-summer film fest season includes heavy-hitters like the San Francisco International Film Festival (April 5-May 29; www.sffs.org); the San Francisco International LGBT Film Festival (June 20-30, www.frameline.org); the San Francisco Silent Film Festival (July 18-21; www.silentfilm.org); and the San Francisco Jewish Film Festival (July 25-Aug. 12; www.sfjff.org).

Elsewhere, the Pacific Film Archive unspools “The Spanish Mirth: The Comedic Films of Luis García Berlanga” (March 29-April 17; bampfa.berkeley.edu); the Vortex Room’s latest weekly double-feature extravaganza, “Assault on Vortex 13,” chock full o’ 1970s and ’80s action flicks, kicks off April 4 (Facebook: The Vortex Room); the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts scores with “Thai Dreams: The Films of Pen-ek Ratanaruang,” with an in-person visit from the groundbreaking artist (April 4-21; www.ybca.org); cult-movie series Thrillville celebrates its 16th anniversary with an April 14 screening of This Island Earth (www.thenewparkway.com); and the best documentary about movie obsession ever, Room 237, opens April 19 at the Roxie (www.roxie.com).

Plus! Contribute at least $40 to the San Francisco Cinematheque’s Kickstarter campaign in support of the group’s experimental and avant-garde Crossroads Film Festival (April 5-7; www.sfcinematheque.org), and get a tote bag featuring naughty ‘n’ nice artwork by the late, great George Kuchar — guaranteed to never go out of style. (Cheryl Eddy)

THEATER: VINTAGE COCKETTES, NEW KUSHNER

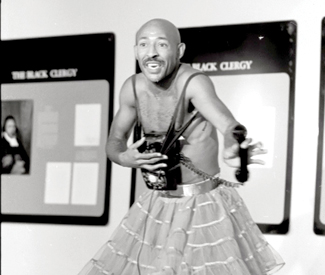

Tinsel Tarts in a Hot Coma (March 28-June 1, Hypnodrome, SF) Making good on a promising trend that began gloriously in 2009 with smash hit Pearls over Shanghai, Thrillpeddlers continues its Theatre of the Ridiculous Revival series with more musical-comedy mayhem from the Cockettes, San Francisco’s own tripping glitter-bearded drag queens of legend. With the full-length restored version of 1971’s Tinsel Tarts in a Hot Coma, the company really pulls out the stops — while stuffing in 14 new songs and roping in, as collaborators and cast members, three original Cockettes: Scrumbly Koldewyn, Rumi Missabu, and “Sweet Pam” Tent. www.thrillpeddlers.com

The Bereaved (April 4-27, Thick House, SF) For several years now my friend John and I have been simultaneously enjoying Thomas Bradshaw’s devilishly smart plays (Purity; Dawn; Strom Thurmond Is Not a Racist; etc.) and wondering when someone in the Bay Area would get around to mounting one. In a West Coast premiere, Crowded Fire essays Bradshaw’s scathingly all-American comedy about a family of fevered New York go-getters — gleefully “inappropriate” enough in its wanton send-up of what passes for normal life to be considered a refreshing provocation amid the usual theater fare. www.crowdedfire.org

Storm and Titania (April 7, Noh Space, SF) This one-night-only engagement, co-presented by foolsFURY, offers the Bay Area its first-ever look at the work of Moon Fool, an innovative physical theater ensemble led by UK-based director-actor-musician Anna-Helena McLean, herself a former lead actor with famous Polish experimental theater company Gardzienice. The evening includes Titania, a widely lauded adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream constructed as a solo cabaret; and a work-in-progress showing of Storm, a new immersive, site-specific spectacle based on The Tempest. www.foolsfury.org

The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide to Capitalism and Socialism with a Key to the Scriptures (May 16-July 7, Roda Theatre, Berk.) It sounded from its initial reviews like something of a hot mess, but it’s apparently been trimmed and fine-tuned, and anyway there’s no missing the West Coast premiere of a new Tony Kushner play — especially one whose title invokes the decidedly odd coupling of George Bernard Shaw and Mary Baker Eddy. Set in Brooklyn amid the extended family of a lefty Italian American longshoreman, The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide promises a fulgurant night of political-philosophical conversation from the stage, bound to stimulate a lot more conversation afterward. www.berkeleyrep.org (Robert Avila)