Gearing up for the end times with Hoodslam

Well another Armageddon scare has come and gone and we’re all still here, as is my dirty laundry which I was letting pile up on the off chance that I wouldn’t need it again. Not that clean clothes were necessary to attend the Judgment Day edition of Oakland-based, amateur-wrestling-and-sideshow-freak extravaganza, Hoodslam.

Housed in the strategically ramshackle Victory Warehouse, a couple of scenic blocks from the Oakland Greyhound station, the Hoodslam ring loomed large in the confines of what could be euphemistically referred to as the foyer. Cheerfully inebriated fans crowded in on three sides, a colorful wall of graffiti framed the fourth, a makeshift door led to the “dressing room,” and a chainlink barrier shielded the house band, Einstye, in classic “Blues Brothers at Bob’s Country Bunker” style. “You can cut the tension in this room with a knife,” wry match commentator Kevin Gill remarked. You could have cut the great cloud of cigarette-booze-and-blunt fumes with same.

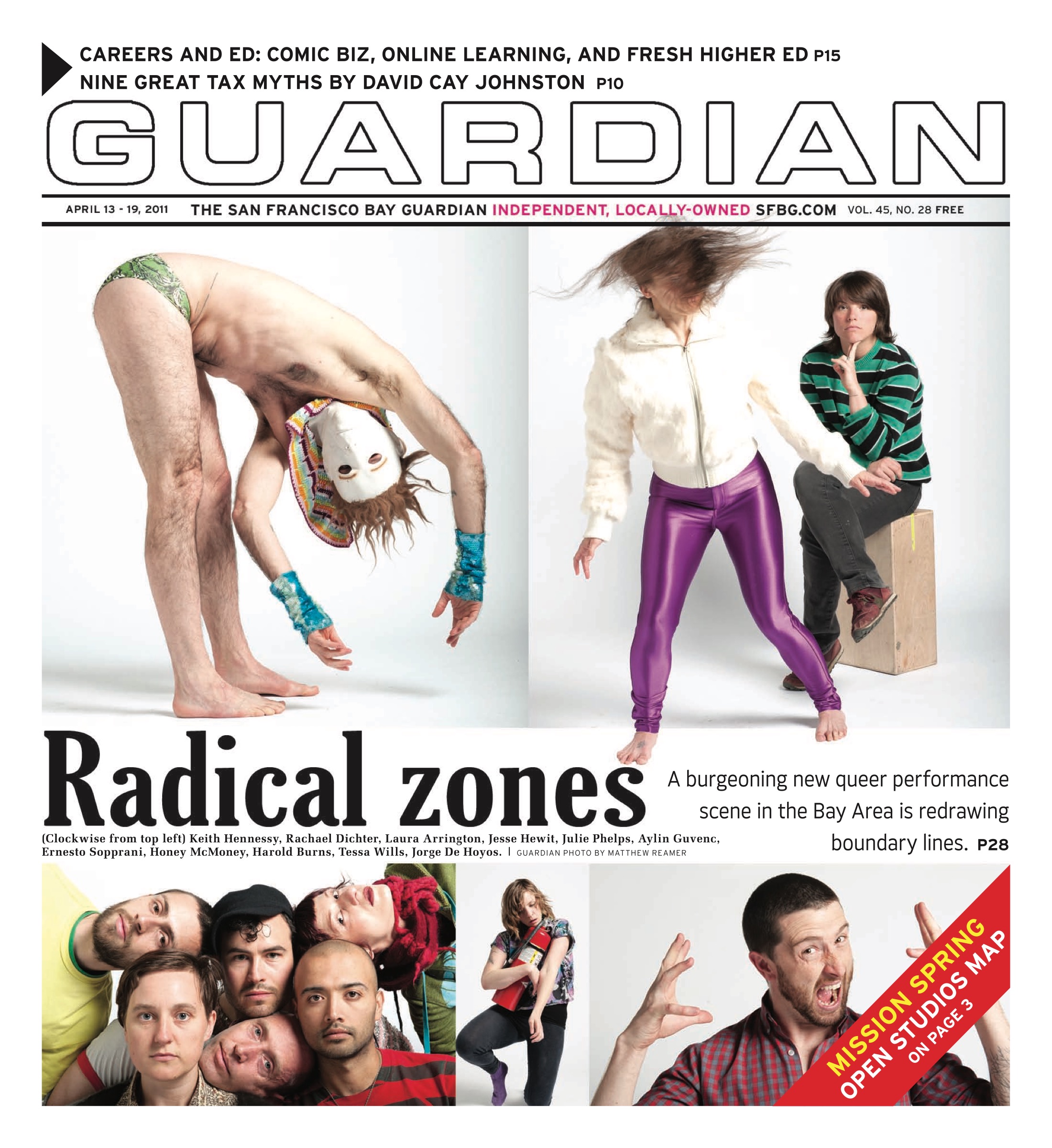

In the best tradition of punk rock wrestling shows like the sorely-missed Incredibly Strange Wrestling, Hoodslam mixes costumed characters, fabricated grudge matches, aggro posturing, loud music, and theatrical bodyslamming with a healthy dose of humor and a pinch of what-the-fuck. But where the flamboyant weirdness of ISW was definitely a product of San Francisco’s love of themed masquerade parties and the slickly produced Lucha Va Voom is 100 percent LA, the scrappy phenomenon that is Hoodslam retains a thoroughly Oakland vibe.

The sensation of being a first-time Hoodslam attendee is something akin to having a crack pipe in one hand and a spliff in the other, with a Steel Reserve going five rounds with a half bottle of NyQuil in the fight cage of your alimentary canal. It’s disorienting. It’s vaguely unsettling. And it’s a hell of a crazy ride.

On Friday, in preparation for the end of the world, a good two dozen Hoodslam “legends” showed up to settle some scores and create new ones (just in case we’d all live to fight another day). Contestants included a bi-polar clown, a French mime, an invisible man, a stampeding rhinoceros, a Winnie-the-Pooh lookalike armed with a garbage can, an unusually tall leprechaun, an Al Bundy clone, ISW remnant Otis the Gimp, the demonic Reverend Hellfyre and his passle of Zombie slaves, and a fanged Mexican werewolf—the dreaded chupacabra!

There were even some wrestlers who could really fight: the acrobatic, bare-chested Juiced Lee for one, and native son, the masked El Lucha Magnifico, “the most evenly-matched men in Hoodslam.”

The unbridled feistiness of the combatants was matched only by the rowdiness of the fans (“fuck the fans,” cheerfully reminded ring announcer Ike Emelio Burner on several occasions), whose profane chanting, frenzied pounding on the mat, and blow-by-blow heckling gave the event a post-apocalyptic edge, though the apocalypse wasn’t scheduled to arrive until the next day.

“Wrestling is a form of theatre designed to generate mass hysteria,” former ISW wrestler and book author Count Dante remarked in his Wired magazine interview. At the smackdown between the mass hysteria of Hoodslam vs. the mass hysteria of the pending Rapture, the former definitely took the win.