OPENING

Brighton Rock Writer Rowan Joffe (2010’s The American) moves into the director’s chair for this Graham Greene adaptation, previously filmed in 1947 with an early-career star turn by Richard Attenborough. Joffe’s version updates Greene’s 1938 story to 1964, allowing the brutal actions of small-time hood Pinkie Brown to unfold as Britain’s mods vs. rockers youth riots boil in the background. Don’t get too excited, though — despite a cool premise and even cooler setting, and the presence of veterans Helen Mirren and John Hurt in supporting roles, Brighton Rock rages without a rudder. Pinkie is played by Sam Riley (so good as Ian Curtis in 2007’s Control), who snarls like a sociopathic James Dean and is so transparently hateful it’s hard to root for anything other than his hastened demise. Brighton Rock‘s most memorable element is probably Andrea Riseborough, an on-the-verge young Brit who’s being touted as the next Carey Mulligan. She has the thankless yet showy role of Rose, a naïve waitress who becomes entangled in Pinkie’s web after being in the wrong place at the wrong time. A far-from-storybook ending awaits, and you’ll experience little enjoyment watching the characters claw their way there. (1:51) Embarcadero. (Eddy)

Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark If you’re expecting a traditional haunted house story, Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark might be a disappointment. The film, which was co-written by Guillermo del Toro, has a lot in common with his Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) — both movies are more dark fairy tale than horror. They follow a young girl who discovers a mystical world around her, much to the disbelief of the adults around her. It’s worth noting that Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark is lighter fare: despite all the peril involved, it’s actually pretty fun. Young Bailee Madison, who made such an impression in 2009’s Brothers, is a charming lead, precocious but believable. And Katie Holmes is surprisingly sympathetic in her role as the caring stepmother, a nice switch from the standard fairy tale trope. As with Fright Night, the ad campaign for Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark is misleading, so here’s hoping audience members looking for a gory slasher will appreciate a whimsical fable instead. (1:40) California. (Peitzman)

*The Hedgehog You needn’t possess the rough, everyday refinement of the characters of The Hedgehog to appreciate this debut feature by director-screenwriter Mona Achache — just an appreciation for a delicate touch and a tender heart. Eleven-year-old Paloma (the wonderful Garance Le Guillermic) is too smart for her own good, bored, neglected by her parents, and left to fend for herself with only her considerable imagination and a camcorder. She drifts around her fishbowl of privilege, a deluxe art nouveau-style apartment building in Paris, leveling her all-too-wise gaze on its denizens and plotting certain suicide on her 12th birthday — that is until a new resident appears in her viewfinder: a kindly Japanese gentleman Kakuro Ozu (Togo Igawa). He has as much of a connoisseur’s eye as Paloma — the proof is in his unlikely focus of attention, the building’s concierge Renée Michel (Josiane Balasko, resembling a burly Gertrude Stein), who hides her cultured and bookish inclinations behind a gruff, drab exterior. They recognize in each other a reverence for an almost monkish life of the mind, the austere elegance of wabi-sabi, and the transient beauty of rough-hewn imperfection, even in the sleek, well-heeled heart of the City of Light. To the credit of Achache, working with Muriel Barbery’s novel, these unlikely fragile friendships between outsiders take hold in a way that sidesteps preciousness and stays with you long after its pages have turned. (1:40) Clay, Shattuck, Smith Rafael. (Chun)

Motherland When Raffi Tang (Francoise Yip) learns of her estranged mother’s death, the prodigal-daughter returns to her hometown, San Francisco, only to discover that nothing is as first supposed. Forced to contend with the protracted legal battle between her late mother and re-married father (Kenneth Tsang) as well as an incompetent (and poorly acted) police detective (Jason Payne), Tang drifts, looking distracted, lost, and maybe vaguely concerned throughout the first two thirds of the film. Yip does little to enliven a flat script rife with stock phrases and worn cinematic conventions, and while her emotional distance seems genuine, it’s boring nonetheless. Motherland is, to its credit, an angry movie — director Doris Yeung drew on her own experience with the murder of her mother — but the rage fizzles when it finally does erupt, smothered by uninspired acting and a directionless screenplay. (1:33) Four Star. (Cooper Berkmoyer)

Our Idiot Brother Paul Rudd is the ne’er-do-well sibling to Emily Mortimer, Elizabeth Banks, and Zooey Deschanel. (1:36) Presidio.

*Shut Up Little Man! An Audio Misadventure Once upon a time (1987 to be exact), two young men moved to San Francisco from the Midwest. Eddie Lee “Sausage” and Mitchell “Mitch D” Deprey wound up living in a somewhat derelict apartment in the Lower Haight. The paint was peeling and the walls were thin, but the rent was cheap. What Eddie and Mitch didn’t count on was having Peter J. Haskett and Raymond Huffman as their neighbors. “You blind cocksucker. You wanna fuck with me? You try to touch me and I will kill you in a fucking minute.” “Shut up! Shut up! Shut up! Shut up little man!” The insults, tantrum throwing, and threats of violence coming from next door were constant. Eddie and Mitch started to lose sleep; after one failed attempt at complaining to Raymond’s face (he threatened death), they started tape-recording the endless geyser of vitriol — first, as possible future evidence, but also out of a growing voyeuristic fascination with these two seniors who had to be the world’s oddest and angriest odd couple. The rest is history. Mitch and Eddie started including snippets of Peter and Ray’s bickering on mix tapes for friends. Somehow, the editor of the now-defunct SF noise music zine Bananafish heard a snippet and approached Mitch and Eddie about distributing compilations of the recordings to a large network of found sound fans. Gradually “Peter and Raymond” became known and much-beloved characters. Their warped repartee inspired several theatrical adaptations, short animated films, pages of comic book panels by artists such as Dan Clowes, and even a one-off single from Devo side project the Wipeouters. Matthew Bate’s documentary Shut Up Little Man! An Audio Misadventure is much an attempt to comprehensively recount the above long, strange trip from start to finish; it is also the newest chapter in the now 20-year saga of Peter, Raymond, Mitch, and Eddie. (1:30) Roxie. (Sussman)

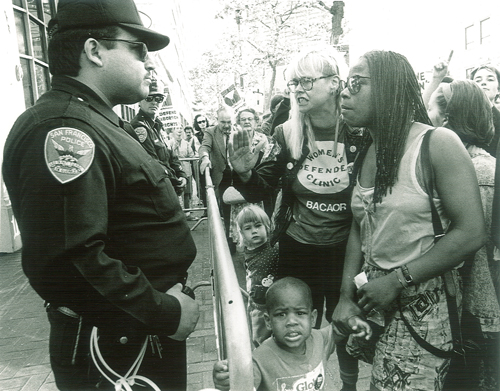

*!Women Art Revolution Bay Area artist and filmmaker Lynn Hershman Leeson’s vibrant look back at the first waves of feminist art in the ’60s and ’70s is an extremely necessary and impassioned recounting of a history that perpetually seems to be on the edge of erasure. Mixing old and new interviews with artists, critics, and scholars — many of which are from Hershman Leeson’s own personal archive — !W.A.R. lets those who stood at the frontlines of one the most significant movements in contemporary art tell their own stories. Seeing and hearing the testimonies of the likes of Yoko Ono, Cindy Sherman, B. Ruby Rich, Judy Chicago, Carolee Scheeman, Rachel Rosenthal, and Ingrid Sischy, one after another, is dazzling — like being in the presence of an Olympian summit — even as their overlapping tales of pushback, casual misogyny and outright ridicule from critics, the art establishment, and in some cases, their colleagues, paint a damning picture of just how endemic sexism was, and as the need for a film such as !WAR attests to, in many ways still is. (1:23) Lumiere, Shattuck. (Sussman)

ONGOING

*The Arbor An audaciously conceived and genuinely haunting chronicle of a family, The Arbor reinvents two of the most debased forms of nonfiction film: the venerating portrait of an artist who died young and the voyeuristic confession of abuse. The locus here is the short, bottle-strewn life of Andrea Dunbar, a brilliant playwright whose work distilled the manners and speech of the West Yorkshire housing projects. The Arbor effectively stages some of this work in a park near the same apartments, but the project’s focus is Dunbar’s shambling private life and its devastating effect on friends, lovers, and daughters. Our emotions are strained by their collective fury and grief, but never cheated. Curiously, Clio Barnard accomplishes this by being up front in her manipulations. After collecting interviews with the key players, she cast actors to lip sync the answers — that is, the voices are documentary while the images are staged, an uncanny effect that becomes even more so when Barnard stitches together responses to narrate a single event. The technique is eerie and literally disembodying. In the same way that one affected by trauma may experience a separation from his or her self, so the image of the actor speaking comes unglued from the “real” voice — and so too is there a crucial hesitation in our assigning authenticity to a single, undivided subject. There are shades of Greek tragedy in The Arbor‘s patient, distanced unfolding of its characters’ fates. The speakers are imagined as a chorus, and though the drama is offscreen, long since buried, the pain still lives. (1:34) Roxie. (Goldberg)

*Beginners There is nothing conventional about Beginners, a film that starts off with the funeral arrangements for one of its central characters. That man is Hal (Christopher Plummer), who came out to his son Oliver (Ewan McGregor) at the ripe age of 75. Through flashbacks, we see the relationship play out — Oliver’s inability to commit tempered by his father’s tremendous late-stage passion for life. Hal himself is a rare character: an elderly gay man, secure in his sexuality and, by his own admission, horny. He even has a much younger boyfriend, played by the handsome Goran Visnjic. While the father-son bond is the heart of Beginners, we also see the charming development of a relationship between Oliver and French actor Anna (Mélanie Laurent). It all comes together beautifully in a film that is bittersweet but ultimately satisfying. Beginners deserves praise not only for telling a story too often left untold, but for doing so with grace and a refreshing sense of whimsy. (1:44) Four Star, Lumiere. (Peitzman)

*Bellflower Picture Two Lane Blacktop (1971) drifters armed with “dude”-centric vocabulary and an obsession with The Road Warrior (1981) and its apocalypse-wow survivalist chic. There are so many pleasures in this janky, so-very-DIY, heavy-on-the-sunblasted-atmosphere indie that you’re almost willing to overlook the clichés, the dead zones, and the annoying characters. Seeming every-dudes Woodrow (director-writer-producer Evan Glodell) and Aiden (Tyler Dawson) are far too obsessed with tricking out their cars and building a flamethrower for their own good — the misfits must force themselves out of the metal shop of the mind to meet women. So when Woodrow goes up against Milly (Jessie Wiseman) in a cricket-eating contest at a bar, it’s love at first bite. Their meet-gross morphs into a road trip and eventually a relationship, while the flamethrower nags, unexplained, in the background, like an unfired gun — or an unconsummated, not-funny bromance. These manifestations of male fantasy — muscle cars, weapons, and tough chicks — are cast in a dreamy, saturated, and burnt-at-the-edges light, as Glodell and company weave together barely articulated reveries and bad-new-west imagery with a kind of fuck-all intelligence, culminating in a finale that will either haunt you with its scattershot machismo-romanticism or leave you scratching your noggin wondering what just happened. (1:46) Sundance Kabuki. (Chun)

Buck This documentary paints a portrait of horse trainer Buck Brannaman as a sort of modern-day sage, a sentimental cowboy who helps “horses with people problems.” Brannaman has transcended a background of hardship and abuse to become a happy family man who makes a difference for horses and their owners all over the country with his unconventional, humane colt-starting clinics. Though he doesn’t actually whisper to horses, he served as an advisor and inspiration for Robert Redford’s The Horse Whisperer (1998). Director Cindy Meehl focuses generously on her saintly subject’s bits of wisdom in and out of a horse-training setting — e.g. “Everything you do with a horse is a dance” — as well as heartfelt commentary from friends and colleagues. In the harrowing final act of the film, Brannaman deals with a particularly unruly horse and his troubled owner, highlighting the dire and disturbing consequences of improper horse rearing. (1:28) Opera Plaza. (Sam Stander)

Captain America: The First Avenger OK, Marvel. I could get behind 2008’s Iron Man (last year’s Iron Man 2, not so much), but after Thor and now Captain America, I’m starting to get cynical about this multi-year build-up to the full-on Avengers movie, due in May 2012. Can even a superhero-stuffed movie directed by Joss Whedon live up to all this hype? There’s plenty of time to ponder, and maybe worry a little, with Captain America’s backstory-explaining picture now in theaters. Chris Evans stars as the 90-pound weakling who morphs into a supersoldier, thanks to the World War II-era tinkerings of a scientist (Stanley Tucci) and an inventor (Dominic Cooper as Howard Stark, a.k.a. Iron Man’s dad). The original plan for the musclebound shield-bearer (fighting Nazis, natch) gets waylaid a bit when the newly famous Captain America becomes a PR prop for the U.S. government; it’s abandoned entirely when a worse-than-Hitler foe, in the guise of power-obsessed Red Skull (Hugo Weaving), threatens the world. Directed by Spielberg cohort Joe Johnston, Captain America is gee-whiz enjoyable enough, but it’s very nearly the same movie as Thor, which no amount of Tommy Lee Jones (as a sarcastic army colonel) wisecracks can conceal. And here’s an anti-spoiler: there’s no post-credits surprise in this one, so you can bolt as soon as they start to roll. (2:09) SF Center, Shattuck. (Eddy)

Conan the Barbarian Neither 3D (unnecessary) nor Jason Momoa (beefcake-y) are enough to make this Conan the Barbarian competition for the 1982 Schwarzenegger classic. This new take is a barely adequate adventure movie helped along by Rose McGowan’s leering turn as an evil witch with Freddy Krueger claws. Would that everyone involved (including frequent remake director Marcus Nispel) had McGowan’s razor-sharp grasp of tone; as a whole, the film is never quite sure if it’s a camp-tastic voyage (the prologue, containing Conan’s birth and much Ron Perlman nostril-flaring, suggests what might have been) or a semi-straightforward fantasy actioner. A totally forgettable female lead (Rachel Nichols), a he-was-scarier-in-Avatar villain (Stephen Lang), a blah mixture of two tired plots (revenge + “chosen one”) — there’s just not a lot here, aside from a few hilarious lines of dialogue and Momoa’s muscles. He was so great in Game of Thrones, though, I suspect this dud won’t keep his career from skyrocketing. (1:42) 1000 Van Ness. (Eddy)

Cowboys and Aliens Here ’tis in a nutshell: the movie’s called Cowboys and Aliens — and that’s exactly, entirely what you’ll get. Director Jon Favreau may never best 2008’s Iron Man (actor Jon Favreau will prob never top 1996’s Swingers, but that’s a debate for another time), but that doesn’t mean he won’t have a good time trying. Cowboys is a genre mash-up in the most literal sense; as the title suggests, it pits Wild West gunslingers (Harrison Ford as a crabby cattleman, Daniel Craig as an amnesiac outlaw) against gold-seeking space invaders who also delight in kidnapping and torturing humans. As stupidly entertaining as it is, this is a textbook example of a pretty OK movie that could have been so much better … if only. If only the alien characters had a little bit more District 9-style personality. If only the story had a shred of suspense — look ye not here for “spooky” and “mysterious;” this shit is 100 percent full-on explosions. If only Craig’s comically fine-tooled physique didn’t outshine his wooden acting. And so forth. (1:58) 1000 Van Ness, SF Center. (Eddy)

Crazy, Stupid, Love Keep the poster’s allusion to 1967’s The Graduate to one side: there aren’t many revelations about midlife crises in this cleverly penned yet strangely flat ensemble rom-com, awkwardly pitched at almost every demographic at the cineplex. There’s the middle-aged romance that’s withered at the vine: nice but boring family man Cal (Steve Carell) finds himself at a hopeless loss when wife and onetime teenage sweetheart Emily (Julianne Moore) tells him she wants a divorce and she’s slept with a coworker (Kevin Bacon). He ends up waxing pathetic at a slick nightclub where he catches the eye of the well-dressed, spray-tanned smoothie Jacob (Ryan Gosling), who appears to have taken his ladies man stance from the Clooney playbook. It’s manly makeover time: GQ meets Pretty Woman (1990)! Cut to Cal and Emily’s babysitter Jessica (Analeigh Tipton), who is crushing out on Cal, while the separated couple’s tween Robbie (Jonah Bobo) hankers for Jessica. Somehow Josh Groban worms his way into the mix as the dullard suitor of Hannah (Emma Stone) in a hanging chad of a storyline that must somehow be resolved in this mad, mad, mad, mad — actually, the problem with Crazy, Stupid, Love is that it isn’t really that crazy. It tries far too hard to please everybody in the theater to its detriment, reminding the viewer of a tidy, episodic TV series (albeit a quality effort) like Modern Family more than an actual film. Likewise I yearned for a way to fast-forward through the too-cute Jessica-Robbie scenes in order to get back to the sleazy-smart, punchy complexity of Gosling, playing adeptly off both Carrell and Stone. (1:58) Marina, 1000 Van Ness, Shattuck, Sundance Kabuki. (Chun)

The Devil’s Double Say hello to my little friend, again— and rest assured, it’s not a dream and you’re seeing double. New Zealand filmmaker Lee Tamahori gets back to his potboiler roots with this campy, claustrophobic look back at the House of Saddam Hussein, based on a true story and designed to win over fans of Scarface (1983) with its portrait of mad excess and deca-dancey ’80s-ish soundtrack. The craziest poseur of all is Hussein’s son Uday (Dominic Cooper), a petty dictator-in-the-making — and, according to this film, a full-fledged murderous pedophile — who chomps cigars and wraps his jaws around schoolgirls while Cooper happily chews scenery. Uday needs a double to sidestep all those troublesome assassination attempts, so he enlists look-alike childhood friend Latif (also Cooper) to get the surgery, pop in the overbite, bray like a madman, make appearances in his stead, and function as a kind of pet human. Never mind Ludivine Sagnier, glassy-eyed and absurd in the role of Uday’s favorite sex kitten Sarrab — Double is completely Cooper’s, who seizes the moment, investing the morally upstanding Latif with a serious sincerity with just his eyes and body language and infusing evil odd job Uday with a dangerous, comic-book unpredictability. To his credit, Cooper imbues such cult-ready, blow-the-doors-off lines as “I love cunt! I love cunt more than god!” with, erm, believability, even as the denouement rings somewhat false. (1:48) Empire. (Chun)

*Final Destination 5 The thing about my undying love for the Final Destination series is that it’s completely legitimate and 100 percent sincere. You know exactly what you’re getting with each new movie, and these films never try to tell you otherwise. Yes, everyone will die. Yes, the deaths will be creative and disgusting. Yes, the quality of acting will be sacrificed for some of the more expensive splatter effects. For those of us who understand what the series is all about, Final Destination 5 is a triumph. It’s gory, wickedly funny, and a notable improvement on previous sequels. Not to mention the fact that Tony “Candyman” Todd gets a beefed-up role. For once, the 3D is actually a big help, with some of the best in-your-face effects I’ve seen. As for non-fans, I can’t say Final Destination 5 has much to offer. You have to embrace the absurdity and the mission statement before you can fully appreciate death by laser eye surgery. (1:32) 1000 Van Ness. (Peitzman)

Fright Night Don’t let the spooky trailer fool you: the Fright Night remake is almost as silly as the original. In fact, it follows the 1985 film closely, as young Charley Brewster (Anton Yelchin) comes to realize that his neighbor Jerry (Colin Farrell) is a vampire. The biggest change is a smart one — this Fright Night transforms late-night TV host Peter Vincent into Criss Angel-type illusionist Peter Vincent (David Tennant). The casting is spot on all-around, and frankly, Farrell is a lot more believable than Chris Sarandon as the seductive bad boy. The only real problem with the new Fright Night — other than the unnecessary 3D — is that it never fully commits to camp the way the original did. There’s a bit too much back-and-forth between serious scares and goofy blood splatters. Luckily, it’s still an entertaining remake that doesn’t crap all over a classic. It’s also a great reminder that vampires don’t have to be moody — remember, they used to be fun. (2:00) 1000 Van Ness, Presidio. (Peitzman)

*The Future Dreams and drawings, cats and fantasies, ambition and aimlessness, and the mild-mannered yet mortifying games people play, all wind their way into Miranda July’s The Future. The future’s a scary place, as many of us fully realize, even if you hide from it well into your 30s, losing yourself in the everyday. But you can’t duck July’s collection of moments, objects, and small gestures transformed into something strangely slanted and enchanted, both weird and terrifying, when viewed through July’s looking glass. Care and commitment — to oneself and others — are two vivid threads running through The Future. Cute couple Sophie (July) and Jason (Hamish Linklater) — unsettling look-alikes with their curly crops — appear at first to be sailing contently, aimlessly toward an undemanding unknown: Jason works from home as a customer-service operator, and Sophie attempts to herd kiddies as a children’s dance instructor. But enormous, frightening demands beckon — namely the oncoming adoption of a special-needs feline named Paw-Paw (voiced by July as if it’s a traumatized, innocent child). Lickety-splitsville, they must be all they can be before Paw-Paw’s arrival. The weirdness of the familiar, and the kindness of strangers, become ways into fantasy and escape when the couple bumps up against the limits of their imagination. This ultra-low-key horror movie of the banal is obviously remote territory for July (2005’s Me and You and Everyone We Know). The Future is her best film to date and finds her tumbling into a kind of magical realism or plastic fantastic, embodied by a talking cat that becomes the conscience of the movie. (1:31) California, Sundance Kabuki. (Chun)

Glee: The 3D Concert Movie (1:30) 1000 Van Ness.

The Guard Irish police sergeant Gerry Boyle (Brendan Gleeson) is used to running his small town on his own terms — not in a completely Bad Lieutenant (1992) kind of way, though he’s not afraid to sample drugs and hang with hookers. More like, he’s been running the show for years, and would prefer that big-city cops stay the hell out of his village. Alas, a gang of drug smugglers is doing business in the area, so an officious group of investigators from Dublin (horrors!) and America (in the form of an FBI agent played by Don Cheadle) soon descend. His mother’s dying, his brand-new partner’s missing, and between all the interlopers on both sides of the law, Boyle’s having a hard time having a pint in peace. Good thing he’s not as simple-minded as all who surround him think he is. Writer-director John Michael McDonagh (brother of playwright Martin, who directed 2008’s In Bruges — also starring Gleeson) puts an affable Irish spin on what’s essentially a pretty typical indie comedy, with some pretty typical crime-drama elements layered atop. Boyle’s character is memorably clever, but the film that contains him never quite elevates to his level. (1:36) Embarcadero, Shattuck, Sundance Kabuki. (Eddy)

Gun Hill Road Though the visibility of gays and lesbians in cinema remains (largely) confined to independent film, Rashaad Ernesto Green, in his debut feature Gun Hill Road, uses the creative freedom afforded by that closeting to explore issues of race and confused sexuality amid the Latino population of the Bronx. Esai Morales is Enrique, a former drug dealer returning from prison to his wife Angela (Judy Reyes) and teenage son Michael (Harmony Santana). But everyone seems to have moved on with their lives. Angela is having an affair, and Michael has created a new persona, Vanessa. Green’s film focuses on the relationship between the damaged Enrique and Michael, whose cross-dressing and budding transsexuality puts the family members at odds. Nominated for the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance and an entry in this year’s Frameline Film Festival, Gun Hill Road is one in a recent spate of films that deals with coming out in an urban setting. Like Green’s film, Peter Bratt’s La Mission (2009) offered a picture of homophobia in the Latino community. But Gun Hill Road, despite its bulging dramatic heft, shirks the after-school-special formula of La Mission by imagining complex characters rather than hewing them from instantly recognizable, sympathetic archetypes. (1:28) Sundance Kabuki. (Ryan Lattanzio)

*Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2 Chances are you aren’t going to jump into the Harry Potter series with Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2. So while the movie is probably the best Harry Potter film yet, it’s more a fitting conclusion than a standalone film. For fans of the books, there are no real surprises — this is a close adaptation. And for those Harry Potter movie fans who haven’t read the books, shame on you, and kudos if you managed to not get spoiled. It’s hard for me to offer a serious critical analysis of Part 2, because it represents the end of a long and very emotional journey. (Everyone in that audience was crying. Everyone.) I will say that, as was the case in the book, there are a few overdone, schmaltzy moments that aren’t really necessary. But in the context of the series, they’re forgivable — this may not be the great cinematic event of our generation, but Harry Potter as a whole is sure to be one of our most enduring cultural icons. (2:10) 1000 Van Ness, Sundance Kabuki. (Peitzman)

The Help It’s tough to stitch ‘n’ bitch ‘n’ moan in the face of such heart-felt female bonding, even after you brush away the tears away and wonder why the so-called help’s stories needed to be cobbled with those of the creamy-skinned daughters of privilege that employed them. The Help purports to be the tale of the 1960s African American maids hired by a bourgie segment of Southern womanhood — resourceful hard-workers like Aibileen (Viola Davis) and Minny (Octavia Spencer) raise their employers’ daughters, filling them with pride and strength if they do their job well, while missing out on their own kids’ childhood. Then those daughters turn around and hurt their caretakers, often treating them little better than the slaves their families once owned. Hinging on a self-hatred that devalues the nurturing, housekeeping skills that were considered women’s birthright, this unending ugly, heartbreaking story of the everyday injustices spells separate-and-unequal bathrooms for the family and their help when it comes to certain sniping queen bees like Hilly (Bryce Dallas Howard). But the times they are a-changing, and the help get an assist from ugly duckling of a writer Skeeter (Emma Stone, playing against type, sort of, with fizzy hair), who risks social ostracism to get the housekeepers’ experiences down on paper, amid the Junior League gossip girls and the seismic shifts coming in the civil rights-era South. Based on the best-seller by Kathryn Stockett, The Help hitches the fortunes of two forces together — the African American women who are trying to survive and find respect, and the white women who have to define themselves as more than dependent breeders — under the banner of a feel-good weepie, though not without its guilty shadings, from the way the pale-faced ladies already have a jump, in so many ways, on their African American sisters to the Keane-eyed meekness of Davis’ Aibileen to The Help‘s most memorable performances, which are also tellingly throwback (Howard’s stinging hornet of a Southern belle and Jessica Chastain’s white-trash bimbo-with-a-heart-of-gold). (2:17) Balboa, California, Empire, 1000 Van Ness, Presidio, SF Center, Sundance Kabuki. (Chun)

Midnight in Paris Owen Wilson plays Gil, a self-confessed “Hollywood hack” visiting the City of Light with his conservative future in-laws and crassly materialistic fiancée Inez (Rachel McAdams). A romantic obviously at odds with their selfish pragmatism (somehow he hasn’t realized that yet), he’s in love with Paris and particularly its fabled artistic past. Walking back to his hotel alone one night, he’s beckoned into an antique vehicle and finds himself transported to the 1920s, at every turn meeting the Fitzgeralds, Gertrude Stein (Kathy Bates), Dali (Adrien Brody), etc. He also meets Adriana (Marion Cotillard), a woman alluring enough to be fought over by Hemingway (Corey Stoll) and Picasso (Marcial di Fonzo Bo) — though she fancies aspiring literary novelist Gil. Woody Allen’s latest is a pleasant trifle, no more, no less. Its toying with a form of magical escapism from the dreary present recalls The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985), albeit without that film’s greater structural ingeniousness and considerable heart. None of the actors are at their best, though Cotillard is indeed beguiling and Wilson dithers charmingly as usual. Still — it’s pleasant. (1:34) Albany, Four Star, Embarcadero, 1000 Van Ness, Piedmont, Sundance Kabuki. (Harvey)

*My Perestroika Robin Hessman’s very engaging documentary takes one very relatable look at how changes since glasnost have affected some average Russians. The subjects here are five thirtysomethings who, growing up in Moscow in the 70s and 80s, were the last generation to experience full-on Communist Party indoctrination. But just as they reached adulthood, the whole system dissolved, confusing long-held beliefs and variably impacting their futures. Andrei has ridden the capitalist choo-choo to considerable enrichment as the proprietor of luxury Western menswear shops. But single mother Olga, unlucky in love, just scrapes by, while married schoolteachers Lyuba and Boris are lucky to have inherited an apartment (cramped as it is) they could otherwise ill afford. Meanwhile Ruslan, once member of a famous punk band (which he abandoned on principal because it was getting “too commercial”), both disdains and resents the new order just as he did the old one. Home movies and old footage of pageantry celebrating Soviet socialist glory make a whole ‘nother era come to life in this intimate, unexpectedly charming portrait of its long-term aftermath. (1:27) Balboa. (Harvey)

*The Names of Love Arthur (Jacques Gamblin) is a 40-ish scientist being interviewed about the threat of a bird flu epidemic when his radio broadcast is interrupted by 20-something Baya (Sara Forestier), who denounces him on-air as a “fascist” for frightening the public. But then, Baya tends to use that label rather indiscriminately, applying it to anyone who might conceivably have views to the right of the dial — and Arthur is in fact a solid liberal, which means she can bed him for love. As opposed to the many, many other men she beds as a self-described “political whore,” seeking out conservative types in order to seduce them and hopefully induce an idealogical shift by whispering sweet nothings (“Not all Arabs are thieves,” etc.) as they orgasm. Raised by parents whose emotions are so tightly wound his mother won’t acknowledge her parents were Jews killed at Auschwitz, Arthur has a hard time adjusting to a relationship with a lover who is faithful emotionally but sees promiscuity as her propagandic gift to the world. Meanwhile Baya’s largely Algerian family treats garrulous political argument as the very air they breathe. This odd-couple story written by Baya Kasmi and director Michel Leclerc deals with serious issues in both humorous and respectful fashion, making for one of the more novel, delightful and depthed French romantic comedies in a long time. Added plus: lots of antic gratuitous nudity. (1:42) Opera Plaza, Smith Rafael. (Harvey)

*One Day Why do romantic comedies get such a bad rap? Blame it on the lame set-up, the contrived hurdles artificially buttressed by the obligatory chorus of BFFs, the superficial something-for-every-demographic-with-ADD multinarrative, and the implausible resolutions topped by something as simple as a kiss or as conventional as marriage, but often no deeper, more crafted, or heartfelt than an application of lip gloss. Yet the lite-as-froyo pleasures of the genre don’t daunt Danish director Lone Scherfig, best known for her deft touch with a woman’s story that cuts closer to the bone, with 2009’s An Education. Her new film, One Day, based on the best-selling novel by David Nicholls, flirts with the rom-com form — from the kitsch associations with Same Time, Next Year (1978) to the trailer that hangs its love story on a crush — but musters emotional heft through its accumulation of period details, a latticework of flashbacks, and collection of encounters between its charming protagonists: upper-crusty TV presenter Dexter (Jim Sturgess) and working-class aspiring writer Emma (Anne Hathaway). Their quickie university friendship slowly unfolds, as they meet every St. Swithin’s Day, July 15, over a span of years, into the most important relationship of their lives. Despite the blue-collar female lead and UK backdrop that it shares with An Education, One Day feels like a departure for Scherfig, who first found international attention for her award-winning Dogme 95-affiliated Italian for Beginners (2000). (1:48) Balboa, Marina, 1000 Van Ness, Piedmont, SF Center, Shattuck. (Chun)

*Point Blank Not for nothing did Hollywood remake French filmmaker Fred Cavaye’s last film, Anything for Her (2008) as The Next Three Days (2010) — Cavaye’s latest, tauter-than-taut thriller almost screams out for a similar rework, with its Bourne-like handheld camera work, high-impact immediacy, and noirish narrative economy. Point Blank — not to be confused with the 1967 Lee Marvin vehicle —kicks off with a literal slam: a mystery man (Roschdy Zem) crashing into a metal barrier, on the run from two menacing figures until he is cornered and then taken out of the action by fate. His mind mainly on the welfare of his very pregnant wife Nadia (Elena Anaya), nursing assistant Samuel (Gilles Lellouche) has the bad luck to stumble on a faux doctor attempting to make sure that the injured man never rises from his hospital bed. As police wrangle over whose case this exactly is — the murder of an industrialist seems to have expanded the powers of the stony-faced, monolithic Commandant Werner (Gerard Lanvin) — Samuel gets sucked into the mystery man’s lot, a conspiracy that allows them to trust no one, and seemingly impossibly odds against getting out of the mess alive. Cavaye never quite stops applying the pressure in this clever, unrelenting cat-and-mouse and mouse-and-his-spouse game, topping it with a nerve-jangling search through a messily chaotic police station. (1:24) Embarcadero, Shattuck. (Chun)

*Rise of the Planet of the Apes “You gotta love a movie where the animals beat up on the humans,” declared my Rise of the Planet of the Apes companion. Indeed, ape must not kill ape, and this Planet of the Apes prequel-cum-remake of Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (1972) takes the long view, back to the days when ape-human relations were still high-minded enough to forbid smart apes from killing those well-armed, not-so-bright humanoids. I was a fan of the original series, but honestly, I approached Rise with trepidation: I dreaded the inevitable scenes of human cruelty meted out to exploited primates — the current wave of chimp-driven films seems focused on holding a scary, shaming mirror up to the two-legged mammalian violence toward their closest living genetic relatives. It’s a contrast to the original series, which provided prisms with which to peer at race relations and generational conflict. But I needn’t have feared this PG-13 “reboot.” There’s little CGI-driven gore, apart from the visceral opening and the showdown, though the heartbreak remains. Scientist Will (James Franco, brow perpetually furrowed with worry) is working to find a medicine designed to supercharge the brain in the wake of Alzheimer’s — a disease that has struck down his father (John Lithgow). When the experimental chimp that responds to his serum becomes violently aggressive, the project is shut down, although the primate leaves behind a surprise: a baby chimp that Will and his father name Caesar and raise like a beloved child in their idyllic Bay Area Victorian. Growing in intelligence as he matures, Caesar finds himself torn by an existential dilemma: is he a pet or a mammal with rights that must be respected? Rise becomes Caesar’s story, rendered in heart-wrenching, exhilarating ways — to director Rupert Wyatt and his team’s credit you don’t miss the performance finesse of Roddy McDowell and Kim Hunter in groundbreaking prosthetic ape face in the original movies — while resolving at least one question about why humans gave up the globe to the primates. One can only imagine the next edition will take care of the lingering question about how even the cleverest of apes will feed themselves in Muir Woods. (1:50) Empire, 1000 Van Ness, Presidio, SF Center, Sundance Kabuki. (Chun)

Sarah’s Key (1:42) Albany, Bridge, Piedmont.

*Senna When Ayrton Senna died in 1994 at the age of 34, he had already secured his legacy as one of the greatest and most beloved Formula One racers of all time. The three-time world champion was a hero in his native Brazil and a respected and feared opponent on the track. This eponymous documentary by director Asif Kapadia is nearly as dynamic as the man himself, with more than enough revving engines and last minute passes to satisfy your lust for speed and a decent helping Ayrton’s famous personality as well. Senna was a champion, driven to win even as the sometimes-backhanded politics of the racing world stood in his way. A tragic figure, maybe, but a legend nonetheless. You don’t have to be an F1 fan to appreciate this film, but you may wind up one by the time the credits roll. (1:44) Embarcadero, Smith Rafael. (Berkmoyer)

Sholem Aleichem: Laughing in the Darkness This documentary cuts to the chase right at the beginning: yeah, Sholem Aleichem was the guy who wrote the Tevye stories that inspired Fiddler on the Roof. But filmmaker Joseph Dorman isn’t trying to make Fiddler: Behind the Musical. Instead, he takes an in-depth look at the life, writing career, and cultural significance of “one of the great modern Jewish writers — and our greatest Yiddish writer,” per the film’s press notes. Fans of Jewish lit will be particularly engaged by Sholem Aleichem’s tale; raised in a shtetl in what’s now the Ukraine, he moved around Europe and to the United States pursuing various careers, but always writing the popular stories that addressed not just Jewish life, but broader issues facing turn-of-the-last-century Jews, including the cross-generational conflicts that make up much of Fiddler‘s plot and humor. That said, this film does rely an awful lot on PBS-style slow pans over black-and-white photos and intellectual talking heads; one suspects the subject himself (so devoted was he to entertaining the regular folk who gobbled up his tales) would’ve preferred his life story to unfold in a livelier fashion. (1:33) Opera Plaza. (Eddy)

Spy Kids: All the Time in the World (1:29) 1000 Van Ness.

30 Minutes or Less In some ways, 30 Minutes or Less is reminiscent of 2008’s Pineapple Express: both are stoner action comedies about normal people shoved into high-stakes criminal activity. But while Pineapple Express was an exciting addition to the genre, 30 Minutes or Less is a flimsy 80-minute diversion that still feels like a waste of time. Jesse Eisenberg plays Nick, a pizza delivery boy who is forced to rob a bank after two would-be criminals strap a bomb to his chest. Strangely, Eisenberg was more charming as Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network (2010) — and his buddy Chet (Aziz Ansari) doesn’t exactly up the likability factor. There’s actually the potential for an interesting story here: something darker seems appropriate, given that 30 Minutes or Less was inspired by a true story with a very unhappy ending. But the film completely fumbles, delivering an action comedy that’s neither tense nor funny. That means the pizza’s free, right? (1:29) 1000 Van Ness, SF Center, Shattuck. (Peitzman)

The Tree of Life Mainstream American films are so rarely adventuresome that overreactive gratitude frequently greets those rare, self-conscious, usually Oscar-baiting stabs at profundity. Terrence Malick has made those gestures so sparingly over four decades that his scarcity is widely taken for genius. Now there’s The Tree of Life, at once astonishingly ambitious — insofar as general addressing the origin/meaning of life goes — and a small domestic narrative artificially inflated to a maximally pretentious pressure-point. The thesis here is a conflict between “nature” (the way of striving, dissatisfied, angry humanity) and “grace” (the way of love, femininity, and God). After a while Tree settles into a fairly conventional narrative groove, dissecting — albeit in meandering fashion — the travails of a middle-class Texas household whose patriarch (a solid Brad Pitt) is sternly demanding of his three young sons. As a modern-day survivor of that household, Malick’s career-reviving ally Sean Penn has little to do but look angst-ridden while wandering about various alien landscapes. Set in Waco but also shot in Rome, at Versailles, and in Saturn’s orbit (trust me), The Tree of Life is so astonishingly self-important while so undernourished on some basic levels that it would be easy to dismiss as lofty bullshit. Its Cannes premiere audience booed and cheered — both factions right, to an extent. (2:18) Four Star, Lumiere, Shattuck. (Harvey)

*The Trip Eclectic British director Michael Winterbottom rebounds from sexually humiliating Jessica Alba in last year’s flop The Killer Inside Me to humiliating Steve Coogan in all number of ways (this time to positive effect) in this largely improvised comic romp through England’s Lake District. Well, romp might be the wrong descriptive — dubbed a “foodie Sideways” but more plaintive and less formulaic than that sun-dappled California affair, this TV-to-film adaptation displays a characteristic English glumness to surprisingly keen emotional effect. Playing himself, Coogan displays all the carefree joie de vivre of a colonoscopy patient with hemorrhoids as he sloshes through the gray northern landscape trying to get cell reception when not dining on haute cuisine or being wracked with self-doubt over his stalled movie career and love life. Throw in a happily married, happy-go-lucky frenemy (comic actor Rob Brydon) and Coogan (TV’s I’m Alan Partridge), can’t help but seem like a pathetic middle-aged prick in a puffy coat. Somehow, though, his confused narcissism is a perverse panacea. Come for the dueling Michael Caine impressions and snot martinis, stay for the scallops and Brydon’s “small man in a box” routine. (1:52) Opera Plaza. (Devereaux)

*Vigilante Vigilante Eschewing any pretense of objectivity and adopting a civic-journalism approach, Bay Area director Max Good and producer Nathan Wollman exhaustively explore the issues at stake in the current graffiti and street art scene by focusing on some unexpected, once-hidden antagonists: the so-called buffers, graffiti abatement advocates, and self-styled vigilantes who obsessively paint over graffiti in cities like Los Angeles (Joe Connolly) and New Orleans (Fred Radtke). Good wraps his interviews with well-known street artists like Shepard Fairey, cultural critics such as Stefano Bloch, and graf advocates a la SF author Steve Rotman around his central pursuit: he’s trying to uncover the identity of the Silver Buff, the mysterious figure who has splashed silver over artwork and tags in Berkeley for more than a decade. After capturing the Buff on camera in the wee hours of the morn, the documentarian get his story — it’s Jim Sharp, a stubborn preservationist intent on “beautifying” the blight, tearing down street posters, picking up trash, and covering over what he sees as vandalism, even if he has to damage the property he claims to be cleaning up. In a witty twist on if-you-can’t-beat-’em-join-’em, Good and Wollman ratchet their tale up a notch when they follow Sharp with colorful paint of their own, brilliantly driving home an appeal for freedom of expression and a reclamation of public space. (1:26) Roxie. (Chun)

The Whistleblower (1:58) Opera Plaza, Shattuck, Smith Rafael.

Film listings are edited by Cheryl Eddy. Reviewers are Kimberly Chun, Michelle Devereaux, Max Goldberg, Dennis Harvey, Louis Peitzman, Lynn Rapoport, Ben Richardson, and Matt Sussman. For rep house showtimes, see Rep Clock.