news@sfbg.com

You can argue about what the word “progressive” means, and you can argue about the process and the politics that put Ed Lee in the Mayor’s Office. And you can talk forever about which group or faction has how much of a majority on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, but you have to admit: this city has just undergone a significant political realignment.

Some of that was inevitable. The last members of the class of 2000, the supervisors who were elected in a rebellion against the sleaze, corruption, and runaway development policies of the Willie Brown administration, have left office. Gavin Newsom, the mayor who was often at war with the board and who encouraged a spirit of rancor and partisanship, is finally off to Sacramento. For the first time since 1978, the supervisors will be working with a mayor they chose themselves.

For much of the past 15 years, progressive politics was as much about stopping bad things — preventing Brown and then Newsom from wrecking the city — as it was about promoting good things. But the “politics of anti,” as San Francisco State political scientist Rich DeLeon describes is, wasn’t a central theme in the November elections, and this generation of supervisors comes into office with a different agenda.

Besides, one of the clear divisions on the board the past seven years was the Newsom allies against the progressives — something that dissipated instantly when Lee took over.

But the realignment goes deeper.

Until recently, the progressives on the board had a working majority — a caucus, so to speak — and they tended to vote together much of the time. The lines on the board were drawn almost entirely by what Newsom disparagingly calls ideology but could more accurately be described as a shared set of political values, a shared urban agenda.

There are still six supervisors who call themselves progressives, but the idea that they’ll stick together was shattered in the battle over a new mayor — and the notion that there’s anything like a progressive caucus died with Board President David Chiu’s election (his majority came in part from the conservative side, with three progressives opposing him) and with Chiu’s new committee assignments, which for the first time in a decade put control of key assignments in the hands of the fiscal conservatives.

A PROGRESSIVE MAJORITY?

The progressive bloc on the board was never monolithic. There were always disagreements and fractures. And, thanks to the Brown Act, the progressives don’t actually meet outside of the formal board sessions. But it was fair and accurate to say that, most of the time, the six members of the board majority functioned almost as a political party, working together on issues and counting on each other for key votes. There was, for example, a dispute two years ago over the board presidency — but in the end, Chiu was elected with exactly six votes, all from the progressive majority that came together in the end.

That all started to fall apart the minute the board was faced with the prospect of choosing a new mayor. For one thing, the progressives couldn’t agree on a strategy — should they look for someone who would seek reelection in November, or try to find an acceptable interim mayor? The rules that barred supervisors from voting for themselves made it more tricky; six votes were not enough to elect any of the existing members. And, not surprisingly, some of the progressives had mayoral ambitions themselves.

When state Assemblymember Tom Ammiano — who would have had six votes easily — took himself out of the running, there was no other obvious progressive candidate. And with no other obvious candidate, and little opportunity for open discussion, the progressives couldn’t come to an agreement.

But by the Jan. 4 board meeting, five of the six had coalesced around Sheriff Mike Hennessey. Chiu, however, was supporting Ed Lee, someone he had known and worked with in the Asian community and whom he considered a progressive candidate. And once it became clear that Lee was headed toward victory, Sup. Eric Mar announced that he, too, would be in Lee’s camp.

A few days later, when the new board convened to choose a president, the progressive solidarity was gone. Sups. David Campos, John Avalos, and Ross Mirkarimi, now the solid left wing of the board, voted for Avalos. Chiu won with the support of Mar, Sup. Jane Kim, and the moderate-to-conservative flank.

Now the Budget Committee — long controlled by a progressive chair and a progressive majority — will be led by Carmen Chu, who is among the most fiscally conservative board members. The Land Use and Development Committee will be chaired by Mar, but two of the three members are from the moderate side. Same goes for Rules, where Sup. Sean Elsbernd, for years the most conservative board member, will work with ideological ally Sup. Mark Farrell on confirming mayoral appointments, redrawing supervisorial districts, and promoting or blocking charter amendments as Kim, the chair, does her best to contain the damage.

You can argue that having independent-minded supervisors who don’t vote as a caucus is a good thing. You can also argue that a fractured left will never win against a united downtown. And both arguments have merit.

But you can’t argue any more that the board has the same sort of progressive majority it’s had for the past 10 years. That’s over. It’s a new — and different — political era.

What happens now? Will the progressives hold enough votes to have an influence on the city budget (and ensure that the deficit solutions include new revenue and not just cuts)? What legislative priorities will the supervisors be pushing in the next year? How will the votes shake out on difficult new proposals (and ongoing issues like community choice aggregation)?

Mayor Lee has pledged to work with the board and will show up for monthly questions. How will he respond to the sorts of progressive legislation — like tenant protections, transit-first policies, immigrant rights measures, and stronger affordable housing standards — that Newsom routinely vetoed?

How will this all play out in a year when the city will also be electing a new mayor?

IDENTITY POLITICS?

When Sups. Chiu, Mar, and Kim broke with their three progressive colleagues to support Chiu for board president — just as Chiu and Mar helped clear the path for Ed Lee to become mayor days earlier — it seemed to many political observers that identity had trumped ideology on the board. There’s some truth to that observation, but it’s too simple an explanation. There’s also the fact that Chiu strongly supported Kim, who is a personal friend and former roommate, in her election, so it’s no surprise she went with him for board president.

And the phrase itself is so laden with baggage and problems that it’s hard to talk about. It has come to signify a wide range of political activity and theorizing founded in the shared experiences of injustice of members of certain social groups. “Rather than organizing solely around belief systems, programmatic manifestoes, or party affiliation, identity political formations typically aim to secure the political freedom of a specific constituency marginalized within its larger context,” says the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, an ongoing research project by the students and faculty at Stanford University.

Although the notion of identity politics took hold during the social movements of the 1960s and ’70s — when liberation and organizing movements among women and various ethic and other identity groups fed a larger liberal democratic surge that targeted war, economic inequity, social injustice, and other issues — it’s also a political approach that has divided the populace.

“One of the central charges against identity politics by liberals, among others, has been its alleged reliance on notions of sameness to justify political mobilization,” says the Stanford Encyclopedia. “Looking for people who are like you rather than who share your political values as allies runs the risk of sidelining critical political analysis of complex social locations and ghettoizing members of social groups as the only persons capable of making or understanding claims to justice.”

Mar explains that the reality of identity politics and whether it’s a factor in the current politics at City Hall is far more complex.

“With me, David Chiu, and Jane Kim as a block of three progressive Asians — and I still define David Chiu as a progressive though I think some are questioning that — we all come out of what I would call a pro-housing justice, transit-first, and environmental sustainability [mindset],” Mar told us. “But I think because of our ethnic background and experiences, we may have different perspectives at times than other progressives.”

For example, Mar said, many working class families of color need to drive a car so they’ll differ from progressives who want to limit parking spaces to discourage driving. He also has reservations about the proposed congestion pricing fee and how it might affect low-income drivers.\

“I think often when progressive people of color come into office — Jane Kim might be one of the best examples — that sometimes there’s an assumption that her issues are going to be the same as a white progressive or a Latino progressive,” he said. “But I think kind of the different identities that we all have mean that we’re more complex.”

Campos, a Latino immigrant who is openly gay, noted that “as a progressive person of color, I have at times felt that the progressive movement didn’t recognize the importance of identity politics and what it means for me to have another person of color in power.”

But, he added, “I don’t think identity politics alone should guide what happens. A progressive agenda isn’t just about race but class, sexual orientation, and other things. It’s not enough to say that identity politics justifies everything.”

University of San Francisco political science professor Corey Cook told the Guardian that identity has always been a strong factor in San Francisco politics, even if it was overshadowed by the political realignment around progressive ideology that occurred in 2000, mostly as a reaction to an economic agenda based on rapid development and political cronyism.

“I’m not sure that identity wasn’t relevant, but it was swamped by ideology,” Cook told the Guardian. Now, he said, another political realignment seems to be occurring, one that downplays ideology compared to the position it has held for the last 10 years. “I’m not sure that ideology is dead. But the dynamics have definitely changed.”

Cook sees what may be a more important change reflected in Chiu’s decision to put the political moderates in control of key board committees. But he said that shift was probably inevitable given the difficulties of unifying the diverse progressive constituencies.

“It’s hard to hold a progressive coalition together, and it’s amazing that it has lasted this long,” he said.

There’s another kind of identity politics at play as well — that of native San Franciscans, who often express resentment at progressive newcomers talking about what kind of city this is, versus those who see San Francisco as a city of immigrants and ideas, a place being shaped by a wider constituency than the old-timers like to acknowledge.

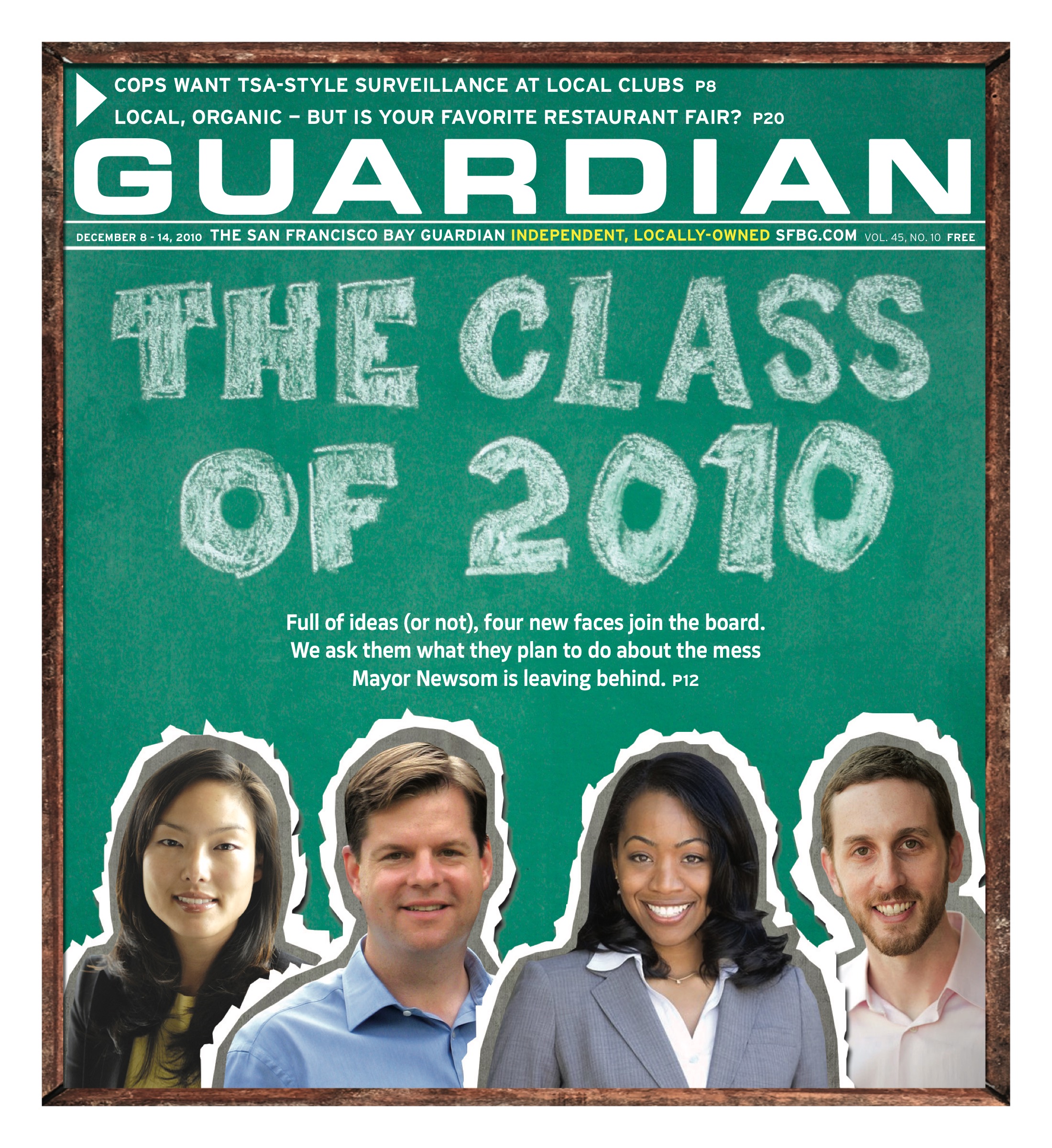

“I’m honored to join Sups. Elsbernd and Cohen in representing the neighborhoods they grew up in,” Sup. Mark Farrell said during his opening remarks after being sworn in Jan. 8., sobbing when he thanked his parents for their support.

As he continued, he fed the criticism of the notion of ideology-based politics that has been a popular trope with Gavin Newsom and other fiscal conservatives in recent years, telling the crowd he wanted “to turn City Hall into a place based on issues and ideas, not ideology.”

Cohen also placed more importance on her birthright than on her political philosophy, telling stories about entering board chambers through the back door at age 16 when she was part of a youth program created by then-Mayor Frank Jordan, and with former Mayor Dianne Feinstein coming to speak at Cohen’s third-grade class. “I am a San Francisco native, and that is a responsibility I take seriously,” said Cohen, who graduated from the Emerge Program, which grooms women for political office,

“We will have another woman as president of the Board of Supervisors, and we will have a woman as mayor of San Francisco,” she added. And as the sole African American on the board, she also pledged, “I will be working to add more members of the African American community to the elected family of San Francisco.”

But what issues she plans to focus on and what values she’ll represent were unclear in her comments — as they were throughout her campaign, despite the efforts of journalists and activists to discern her political philosophy. In her public comments, her only stated goal was to build bridges between the community and City Hall and let decisions be guided by the people “not political ideologies.”

Oftentimes in recent San Francisco history, identity and ideology have worked in concert, as they did with former Sup. Harvey Milk, who broke barriers as the first openly gay elected official, but who also championed a broad progressive agenda that included tenants rights, protecting civil liberties, and creating more parks and public spaces.

Sup. Scott Wiener, shortly after being sworn into office, acknowledged the legacy of his district, which was once represented by Milk and fellow gay progressive leader Harry Britt, telling the crowd: “I’m keenly aware of the leadership that has come through this district and I have huge shoes to fill.”

Yet Wiener, a moderate, comes from a different ideological camp than Milk and Britt and he echoed the board’s new mantra of collaboration and compromise. “I will always try to find common ground. There is always common ground,” he said.

GETTING THINGS DONE?

Chiu is making a clear effort to break with the past, and has been critical of some progressive leaders. “I think it’s important that we do not have a small group of progressive leaders who are dictating to the rest of the progressive community what is progressive,” he said.

While he didn’t single out former Sup. Chris Daly by name, he does seem to be trying to repudiate Daly’s leadership style. “I think that while the progressive left and the progressive community leaders have had very significant accomplishments over the past 10 years, I do think that there are many times when our oppositional tactics have set us back.”

When Chiu was reelected board president, he told the crowd that “none of us were voted into office to take positions. We were voted into office to get things done.”

Some progressives were not at all happy with that comment. “I thought that was a terrible thing to say,” Avalos told the Guardian, arguing the positions that elected officials take shape the legislation that follows. As an example, he cited the positions that progressive members of Congress took in favor of the public option during the health care reform debate.

Talking about getting things done is “a sanctimonious talking point that fits well with what the Chronicle and big papers want to hear,” Avalos said. He said the Chronicle and other downtown interests are more interested in preserving the status quo and blocking progressive reforms. “It’s what they want to see not get done.”

Campos even challenged the comment publicly during the Jan. 11 board meeting when he said, “It’s important to get things done, but I don’t think getting things done is enough. We have to ask ourselves: what is it that we’re getting done? How is it that we’re getting things done? And for whom is it that we’re doing what we’re doing? Is it for the people, or the downtown corporate interests? I hope it’s not getting things done behind closed doors.”

Chiu said that, for him, getting things done is about expanding the progressive movement and consolidating its recent gains. “I think we all share a political goal. As progressives, we all share a political goal of getting things done and growing mainstream support for our shared progressive principles so that they really become the values of our entire city.”

To do that, he said, progressives are going to need to be more conciliatory and cooperative than they’ve been in the past. “I think it’s easy to slip into a more oppositional way of discussing progressive values, but I’m really pushing to move beyond that.”

The biggest single issue this spring will be the budget — and it’s hard to know exactly where the board president will draw his lines. “I have spoken to Mayor Lee about the need for open, transparent, and community-based budget processes and he’s open to that,” Chiu told us — and that alone would be a huge change. But the key progressive priority for the spring will be finding ways to avoid brutal budget cuts — and that means looking for new revenue.

When asked whether new general revenue will be a part of the budget solution, instead of Newsom’s Republican-style cuts-only approaches, Chiu was cautious. “I am open to considering revenues as part of the overall set of solutions to close the budget deficit,” he said. “I am willing to be one elected here that will try to make that argument.” But with his political clout and connections right now, he can do a lot more than be one person making an argument.

Chiu has always been open to new revenue solutions and even led the way in challenging the cuts-only approach to both the city budget and MTA budget two years in a row, only to back down in the end and cut a deal with Newsom. When asked whether things will be better this year given his closer relationship to Lee, Chiu replied, “I think things are going to be different in the coming months.”

During the board’s Jan. 7 deliberation on Lee, Sup. Eric Mar also said that based on his communications with Lee, Mar believed that the Mayor’s Office is open to supporting new revenue measures. He echoed the point later to us.

In addition to supporting the open, inclusive budget process, Mar called for “a humane budget that protects the safety net and services to the most vulnerable people in San Francisco is kind of the critical, top priority.

“I think it’s going to be difficult working with the different forces in the budget process,” he added. “That’s why I wish it could have been a progressive who was chairing the budget process.”

Mar said progressive activism on the budget process is needed now more than ever. “The Budget Justice Coalition from last year I think has to be reenergized so that so many groups are not competing for their own piece of the pie, but that it’s more of a for-all, share-the-pain budget with as many people communicating from outside as possible, putting the pressure on the mayor and the board to make sure that the critical safety net’s protected.”

CUTS WILL BE CENTER STAGE

But major cuts — and the issue of city employees pay and benefits — will also be center stage.

At the board’s Jan. 11 meeting, before the supervisors voted unanimously to nominate Lee as interim mayor, Sup. Elsbernd signaled that city workers’ retirement and health benefits will once again be at the center of the fight to balance the budget.

Elsbernd noted that in past years he was accused of exaggerating the negative impacts that city employees’ benefits have on the city’s budget. “But rather than being inflated, they were deflated,” Elsbernd said, noting that benefits will soon consume 18.14 percent of payroll and will account for 26 percent in three years.

“Does the budget deficit include this amount?” he asked.

And at the after-party that followed Lee’s swearing-in, Public Defender Jeff Adachi, who caused a furor last fall when he launched the ill-considered Measure B, which sought to reform workers’ benefits packages, told us he is not one to give up lightly.

“We learned a lot from that,” Adachi said. “This is still the huge elephant in City Hall. The city’s pension liability just went up another 1 percent, which is another $30 million”

Chu agreed that worker benefits would be a central part of the budget-balancing debate. “Any conversation about the long-term future of San Francisco’s budget has to look at the reality of where the bulk of our spending is,” she said.

Avalos noted that he plans to talk to labor and community based organizations about ways to increase city revenue. “I’m going to work behind the scene on the budget to make sure the communities are well-spoken for,” Avalos said, later adding, “But it’s hard, given that we need a two-thirds majority to pass stuff on the ballot.”

Last year, Avalos helped put two measures on the ballot to increase revenue: Prop. J, which sought to close loopholes in the city’s current hotel tax and asked visitors to pay a slightly higher hotel tax (about $3 a night) for three years, and Prop. N, the real property transfer tax that slightly increased the tax charged by the city on the sale of property worth more than $5 million.

Prop. N should raise $45 million, Avalos said. “I’ve always had my sights set on raising revenue, but making cuts is inevitable.”

THE IDEOLOGY ARGUMENT

Newsom and his allies loved to use “ideology” as a term of disparagement, a way to paint progressives as crazies driven by some sort of Commie-plot secret agenda. But there’s nothing wrong with ideology; Newsom’s fiscal conservative stance and his vow not to raise taxes were ideologies, too. The moderate positions some of the more centrist board members take stem from a basic ideology. Wiener, for example, told us that he thinks that in tough economic times, local government should do less but do it better. That’s a clear, consistent ideology.

For much of the past decade, the defining characteristic of the progressives on the board has been a loosely shared urban ideology supported by tenants, immigrant-rights groups, queer and labor activists, environmentalists, preservationists, supporters of public power and sunshine and foes of big corporate consolidation and economic power. Diversity and inclusiveness was part of that ideology, but it went beyond any one political interest or identity group.

It was often about fighting — against corruption and big-business hegemony and for economic and social equality. The progressive agenda started from the position that city government under Brown and Newsom had been going in the wrong direction and that substantive change was necessary. And sometimes, up against powerful mayors and their well-heeled backers, being polite and accommodating and seeking common ground didn’t work.

As outgoing Sup. Daly put it at his final meeting: “I’ve seen go-along to get along. If you want to do more than that, if you think there’s a fundamental problem with the way things are in this world, then go-along to get along doesn’t do it.” When Chiu announced that the new progressive politics is one of pragmatism, he was making a break from that ideology. He was signaling a different kind of politics. He has urged us to be optimistic about the new year — but we still don’t know what the new agenda will look like, how it will be defined, or at what point Chiu and his allies will say they’ve compromised and reached out enough and are ready to take a strong, even oppositional, stand. We do know the outcome will affect the lives of a lot of San Franciscans. And when the budget decisions start rolling down the pike, the political lines will be drawn fairly clearly. Because reaching across the aisle and working together sounds great in theory — but in practice, there is nothing even resembling a consensus on the board about how the city’s most serious problems should be resolved. And there are some ugly battles ahead.