Sarah@sfbg.com

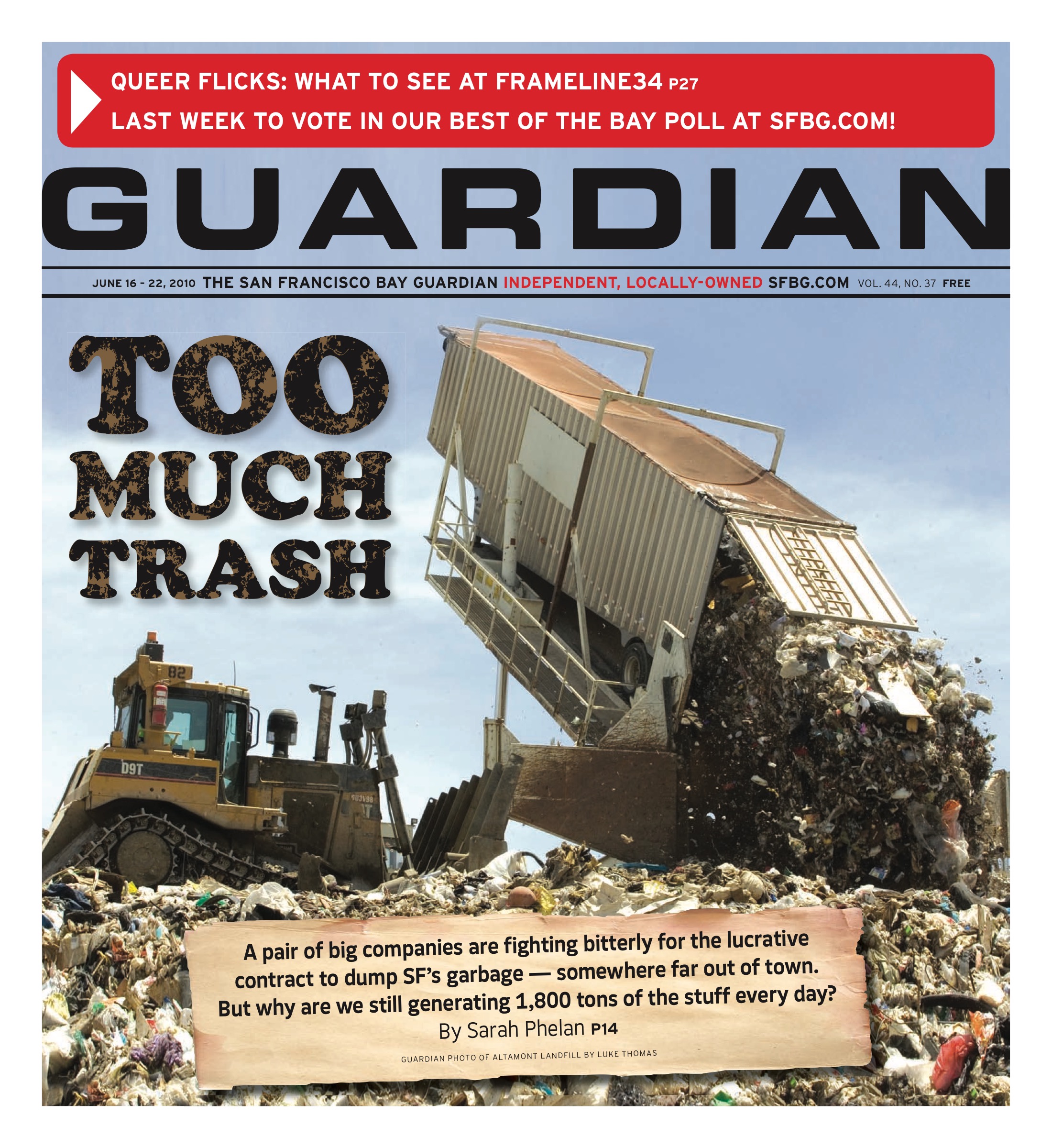

Everyone should make a pilgrimage to the landfill where their city’s garbage is buried. For San Francisco residents to really understand the current trash situation — and its related issues of transportation, environmental justice, greenhouse gas reduction, corporate contracting, and pursuing a zero waste goal — that means taking two trips.

The first is a relatively short trek to Waste Management’s Altamont landfill in the arid hills near Livermore, which is where San Francisco’s trash has been taken for three decades. The next is a far longer journey to the Ostrom Road landfill near Wheatland in Yuba County, a facility owned by Recology (formerly NorCal Waste Systems, San Francisco’s longtime trash collector) on the fertile eastern edge of the Sacramento Valley, where officials want to dispose of the city’s trash starting in 2015.

Both these facilities looked well managed, despite their different geographical settings, proving that engineers can place a landfill just about anywhere. But landfills are sobering reminders of the unintended consequences of our discarded stuff. Plastic bags are carried off by the wind before anyone can catch them. Gulls and crows circle above the massive piles of trash, searching for food scraps. And the air reeks of methane, a potent greenhouse gas that is second only to carbon dioxide as a manmade cause of global warming.

It’s also a reminder of a fact most San Franciscans don’t think much about: The city exports mountains of garage into somebody else’s backyard. While residents have gone a long way to reduce the waste stream as city officials pursue an ambitious strategy of zero waste by 2020, we’re still trucking 1,800 tons of garbage out of San Francisco every day. And now we’re preparing to triple the distance that trash travels, a prospect some Yuba County residents find troubling.

“The mayor of San Francisco is encouraging us to be a green city by growing veggies, raising wonderful urban gardens, composting green waste and food and restaurant scraps,” Irene Creps, a San Franciscan who owns a ranch in Wheatland, told us. “So why is he trying to dump San Francisco’s trash in a beautiful rural area?”

Behind that question is a complicated battle with two of the country’s largest private waste management companies bidding for a lucrative contract to pile San Francisco’s trash into big mountains of landfill far from where it was created. This is big and dirty business, one San Francisco has long chosen to contract out entirely, unlike most cities that at least collect their own trash.

So the impending fight over who gets to profit from San Francisco’s waste, a conflict that is already starting to get messy, could illuminate the darker side of our throwaway culture and how it is still falling short of our most wishful rhetoric.

TALKING TRASH

The recent recommendation by a city committee to leave the Altamont landfill and turn almost all the city’s waste functions — collection, sorting, recycling, and disposal — over to Recology (see “Trash talk,” 3/30) angered Waste Management as well as some environmentalists and Yuba County residents.

WM claimed the contract selection process had been marred by fraud and favoritism, and members of YUGAG( Yuba Group Against Garbage) charged that sending our trash on a train through seven counties will affect regional air quality and greenhouse gas emissions and target a poor rural community. Observers also want details such as whether San Francisco taxpayers will have to pay for a new rail spur and a processing facility for organic matter.

Mark Westlund of the Department of Environment told the Guardian that negotiations between the city and Recology are continuing and the contract bids remain under seal. “Hopefully they’ll be concluded in the near future,” Westlund said. “I can’t pinpoint an exact date because the deal is still being fleshed out, but some time this summer.”

Under the tentative plan, Recology’s trucks would haul San Francisco’s trash across the Bay Bridge to Oakland, where the garbage would be loaded onto trains three times a week and hauled to Wheatland. Recology claims its proposal is better for the environment and the economy because it takes trucks off the road and removes organic matter from the waste before it reaches the landfill and turns into methane gas.

But WM officials reject the claim, noting that both facilities will convert methane to electricity, energy now used to fuel the trucks going to Altamont. The landfill produces 8.5 MW of electricity annually, some of which is converted into 4.7 million gallons of liquid natural gas used by 300 trucks. The Ostrom Road facility would produce far less methane, using it to create 1.5 MW of electricity annually.

Recology officials say removing organic matter to produce less methane is an environmental plus because much of the methane from Altamont escapes into the atmosphere and adds to global warming, although WM claims to capture 90 percent of it. Yet David Assman, deputy director of the San Francisco Department of the Environment, doesn’t believe WM figures, telling us that they are “not realistic or feasible.”

State and federal environmental officials say about a quarter of the methane gas produced in landfills ends up in the atmosphere. “But they acknowledge that this is an average. Some landfills can be worse, others much better if they have a good design. And there is no company that has done as much work on this as Waste Management,” company spokesperson Chuck White told us, citing WM-sponsored studies indicating a methane capture rate as high as 92 percent. “The idea of 90 percent capture of methane is very credible if you are running a good operation.”

Ken Lewis, director of WM’s landfills, said the facility’s use of methane to cleanly power its trucks has been glossed over in the debate over this contract. “We’re just tapping into the natural carbon cycle,” Lewis told us.

But Recology spokesperson Adam Alberti (who works for Singer & Associates, San Francisco’s premier crisis communications firm) counters that it’s better to avoid producing methane in the first place because some of it escapes and adds to global warming, which Recology claims it will do by sorting the waste, in the process creating green jobs in the organics recycling and reducing the danger of the gases leaking or even exploding.

“But what has Recology done to show us that the capture rate at their Ostrom landfill is on the high side?” Lewis asks. “Folks in San Francisco say it’s not possible, but we’ve got published reports.”

Assman admits that San Francisco won’t be able to ensure that other municipalities that use Ostrom Road will be focusing on organics recycling. While questions remain about how that facility will ultimately handle a massive influx of garbage, Altamont has been housing the Bay Area’s trash for decades. And even though San Francisco’s current contract will expire by 2015, this sprawling facility nestled in remote hillsides can still handle more trash for decades to come.

ZERO SUM

Perhaps the most striking aspect of the Altamont landfill is the 30-foot-tall fence that sits on a ridge on the perimeter of the facility. It’s covered with plastic bags that have escaped the landfill and rolled like demonic tumbleweeds along what looks like a desolate moonscape.

Wind keeps the blades turning on the giant Florida Power-owned windmills that line the Altamont hills, but it also puffs plastic bags up like little balloons that take off before the bulldozers can compress them into the fill. Lewis said he bought a special machine to suck up the bags, and employs a team of workers to collect them from the buffer zone surroundinge site.

Although difficult to control or destroy, plastic bags are not a huge part of the waste volume. San Francisco has already banned most stores from using them, and the California Legislature is contemplating expanding the ban statewide in a effort to limit a waste product now adding to a giant trash heap in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

“Plastic bags are a visual shocker,” said Marc Roberts, community development director for the city of Livermore. “In that sense, they are similar to Styrofoam. It’s pretty nasty stuff, can get loose, and doesn’t break down. But they’re not a major part of the volume.”

Yet Roberts said that these emotional triggers give us a peek into the massive operations that process the neverending stream of waste that humans produce and don’t really think about that often.

“Our world is so mechanized,” Roberts observed. “Stuff disappears in middle of night, and we don’t see where it goes.”

San Francisco officials confirm that the trend of disappearing stuff in the night will continue, no matter which landfill waste disposal option the city selects.

“No matter what option, it’s going to involve some transportation to wherever,” Assman said. Currently, Recology and WM share control over San Francisco’s waste stream. But that could change if the waste disposal contract goes to Recology.

A privately-held San Francisco firm, Recology has the monopoly over San Francisco’s waste stream from curbside collection to the point when it heads to the landfill. Waste Management, a publicly-traded company that is the nation’s largest waste management operation, owns 159 of the biggest landfills in the nation, including Altamont, the seventh-largest capacity landfill in the nation.

San Francisco started sending its trash to Altamont in 1987, when it entered into a contract with Waste Management for 65 years or 15 million tons of capacity, a level expected to be hit by 2015, triggering the current debate over whether it would be better to send San Francisco’s waste on a northbound train.

TRAIN TO WHEATLAND

Creps, 76, a retired school teacher, warns folks to watch out for rattlesnakes as she shows them around this flood-prone agricultural community.

“This is an ancient sea terrace, and now it’s fertile grazing ground between creeks,” Creps said as we walked around the ranchland that Creps’ grandfather settled when he came to California in 1850. Today he lies buried here in a pioneer cemetery, along with Creps’ adopted daughter, Sophie, who was killed at age 27 after she witnessed a friend’s murder in Oakland in 2006.

Creps’ cousin, Bill Middleton, who grows walnuts on a ranch adjacent to hers, worries about the landfill’s potential impact on the groundwater. “The water table is really high here, so you’ve go a whole pond of water sitting under this thing,” Middleton said.

Wheatland’s retired postmaster, Jim Rice, recalled that when the landfill opened on Ostrom Road in the 1980s, individual cities had veto power over any expansion plans. “But Chris Chandler, who was then the Assembly member for Sutter County and is now a judge, carried a bill in legislature to do away with veto power,” Rice said.

“So we lost out and ended up with a dump,” Middleton said.

Creps believes the landfill should be for the use of local residents only. “There’s a lot of development going on around here and the population is going to grow,” she said. “But at this rate, this landfill will be used up before Yuba and the surrounding counties can use it. And that’s not fair. They think they can get a foothold in places off the beaten path.”

Yet not everyone in Yuba County hates San Francisco’s Ostrom Road plan. On June 7, the Yuba-Sutter Economic Development Corporation backed Recology’s plan to build a rail spur to cover the 100 yards from the Union Pacific line to the landfill site.

EDC’s Brynda Stranix said the garbage deal is still subject to approval by San Francisco officials, but will bring needed money to the county. “The landfill is already permitted to take up to 3,000 tons of garbage a day and it’s taking in about 800 tons a day now,” Stranix said.

If the deal goes through, it would triple the current volume at the landfill, entitling Yuba County to $22 million in host fees over 10 years.

Recology’s Phil Graham clarified that Ostrom Road is considered a regional landfill, one that has already grown to 100 feet above sea level and is permitted to rise another 165 feet into the air. “So even with the waste stream from San Francisco,” he said, “we’ll still be operating well under the tonnage limits.”

“The world has changed. Federal regulations come in, and landfill operations change,” Recology’s Alberti said as we toured the site. “And there really are no longer any local landfills. This one is already operating, accepting regional waste.”

He claimed that Livermore residents had similar concerns to those now expressed in Yuba County when San Francisco’s waste started going to Altamont. Livermore and Sierra Club brought a lawsuit around plans to expand the dump, a suit that forced WM to create an $10 million open space fund.

Alberti said he understands that people like Creps are concerned. “But we are not seeking an expansion. The only thing we are asking for is a rail track.

“From our point of view it’s simple,” he continued. “We have the facility; Ostrom Road is close to rail; and it’s not open to the public. So it’s a tightly contained working area.”

Graham, the facility’s manager, also dismissed concerns that the landfill might harm the groundwater or the health of the local environment. “A lot of people don’t know how highly regulated we are,” he said. “That’s why we are having public meetings. Our compass is out in the community. These are people we work and live with.”

Alberti said YUGAG and other opponents of the landfill aren’t numerous. “If we draw the circle wider to the two-county area, how many people even know a landfill is operating here?”

Graham takes that as a testament to how well the facility is operated. “I consider that a compliment. Obviously, we weren’t causing any problems.”

TRASH MONOPOLY

Those who run both landfills say they recognize that their industry’s heyday is over, and that the future will bring a more complicated system that sends steadily less trash to the landfills.

“Eventually we will be all out of business,” Alberti predicted. “One reason we changed our name was knowing that landfills are not sustainable. And that’s a significant difference. Waste Management is the largest landfill owner in the world. Recology is a recycling company that owns a few landfills and, for that reason, does innovative things like the food scraps program.”

But the company with the new green name has traditionally been a powerhouse in San Francisco’s trash industry, becoming a well-entrenched monopoly after buying out two local competitors — Sunset Scavenger and Golden Gate Disposal and Recycling — a triad that has long held exclusive rights over the city’s waste.

The 1932 Refuse Collection and Disposal Ordinance gave the company now calling itself Recology a rare and enviably monopoly on curbside collection, one that had no expiration date and would be difficult to change. “So legally, it’s not an option,” Assman said.

Retired Judge Quentin Kopp, a former member of the Board of Supervisors and California Legislature, got involved in an unsuccessful effort to break Recology’s curbside monopoly in the 1990s when the company then known as NorCal Waste asked for another rate increase. But he found the contractual structure to be almost impossible to break.

“The DPW director examines all the allowable elements and makes recommendations to the Rate Board,” Kopp said. “And the Rate Board consists of three people: the chief administrative officer, the controller, and the general manager of the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission.”

SFPUC General Manager Ed Harrington says Recology’s curbside monopoly is unusual compared to other places, but it also makes the company a strong contender to the landfill contract. “It comes down to economies of scale. If you don’t have a contract with a facility that does recycling or waste disposal, you can collect the garbage, but where are you going to take it?”

Harrington said the situation was better before Recology purchased Sunset Scavenger, which mostly handled residential garbage, and Golden Gate, which mostly handled commercial garbage. Today, he said, the city has little control over commercial garbage rates or Recology’s overall finances. “That made it more difficult, and we only set the rate of residential garbage collection,” Harrington observed. “They have never come before the rate appeal board over commercial rates. I have asked who subsidizes whom, the commercial or the residential, and they say they think the commercial. But we have no ability to govern or manage those rates.”

WM’s Skolnick said a positive outcome of the current contract negotiations would be to break Recology’s monopoly on curbside collection. “We have to work to keep our business. That’s the competitive process. But we have a competitor that can encroach into our area even though we can’t encroach on San Francisco. And they claim to have one of the most competitive rates in the country — but try getting those numbers,” he said.

WM’s David Tucker added: “We’d like if San Francisco jumped into the 21st century and had a competitive bid process.”

DIRTY BUSINESS

The battle between WM’s local landfill option and Recology’s plan for a longer haul but with more diversion of organic materials is complicated, so much so that the local Sierra Club chapter has yet to take a position.

Glen Kirby of the Sierra Club’s Alameda County chapter told the Guardian that the Sierra Club’s East Bay, San Francisco, and Yuba chapters are taking a “wait and see what becomes public next” stance for now. But insiders say the club’s national position is against landfill gas conversion projects like that at Altamont, possibly favoring Recology’s bid.

Recology proponents claim the Sierra Club didn’t initially oppose landfill gas conversions because its members in the East Bay benefit from an open space fund that WM pays into as mitigation for a 1980 expansion at the Altamont. And Alberti claimed that WM’s analysis of greenhouse gas emissions from the competing waste transportation plans was flawed.

“Their calculation is a shell game. And it relies on Recology using diesel when we are using green biodiesel trains. This is not your grandfather’s train any more. One train equals 200 trucks,” Alberti said.

But WM’s Lewis defends the company’s analysis, which showed Recology’s bid to be worse for greenhouse gas emissions than WM’s.

“Landfill gas is a byproduct of an existing system,” Lewis said, noting that 43 percent of the trash buried at Altamont comes from San Francisco. The implication is that a large part of the methane in the landfill comes from — and benefits — San Francisco.

“We are delivering waste products that contain organics,” he said. “We realized that we could flare methane [to burn it up] or produce electricity. California has very aggressive landfill gas requirements, and the collection rates are relatively good at most sites. But once you’ve collected it, what to do? Historically, they flared the gas. Twenty years ago, there was not a lot of technology to allow anything else.”

Lewis says WM began producing electricity from the gas in 1987. “What we do in the future is decoupled from what was giving us the methane in the past,” he said. “Today we are managing what was brought here 15-20 years ago. It’s your hamburger, cardboard, and paper that has been sitting up there since 1998. We’re doing something good with something that we used to flare.”

“If Altamont was closed today, the gas yield coming off it would be enough to produce 10,000 gallons a day for the next 25 years,” WM’s Bay Area president Barry Skolnick interjected.

And Lewis observed that if you take organics out of the waste stream, as Recology proposes, that matter has value, whether in a digester to produce energy or a composting operation. That complicates the comparison of the two bids.

“We agree that if you can get that waste out in a clean form, that’s a good thing,” Lewis said. “But composting is a very highly polluting approach. In the process of degrading, it gives off a lot of volatiles and carbon dioxide. So air districts have not traditionally been very positive on sitting aerobic composting facilities.”

WHAT’S NEXT?

The contract that San Francisco has tentatively awarded to Recology is for 5 million tons or 10 years, whichever comes sooner. As such, it’s a much smaller contract than the city’s 1987 contract with WM, mostly because the future is uncertain.

But trucks will remain a part of the equation. Recology is proposing to continue driving 92 truckloads of garbage over the Bay Bridge per day, possibly to keep the Teamsters happy, frustrating transportation advocates who believe direct rail haul or barges across the bay would be greener options.

In December 2009, Mayor Gavin Newsom and Bob Morales, director of the Teamsters Union Waste Division, cowrote an op-ed in the Sunday Sacramento Bee, in which they argued the case for increased recycling and composting as a “zero waste” strategy for California and as a way to generate green jobs and reduce global warming.

“Equally important for the future of our green economy is that recycling and composting mean jobs,” Newsom and Morales wrote. “The Institute for Local Self-Reliance reports that every additional 10,000 tons recycled translates into 10 new frontline jobs and 25 new jobs in recycling-based manufacturing.”

Newsom and Morales clarified that they do not support waste-to-energy or landfilling as part of their zero waste vision.

“It makes no sense to burn materials or put them in a hole in the ground when these same materials can be turned into the products and jobs of the future,” they stated.

Yet WM’s Skolnick sees a certain hypocrisy in San Francisco turning its back on the methane gas that its garbage helped create at Altamont over the past three decades. “Here’s a very progressive city, and we want to take their waste from the last 30 years and use gas from it to fuel their trucks,” he said. “But they want to haul waste three times as far to Wheatland. What does that say about San Francisco’s mission to become the greenest city?”

David Pilpel, a political activist who has followed the contract, agreed that San Francisco officials can’t simply walk away from Altamont and call it a green move, but he would like to see the city use rail rather than trucks. “Instead of putting stuff on long-haul trucks, put it on a rail gondola and haul it around the peninsula to Livermore,” he said. “The Altamont expansion was for San Francisco’s purposes. So to say now, ‘We’ll go elsewhere,’ is lame.”

Sally Brown, a research associate professor at the University of Washington, acknowledges that landfills have done a great job of giving us places to dump our stuff and can be skillfully engineered to release less methane and capture more productive biogases.

“However, we are entering a new era where resources are limited and carbon is king,” Brown wrote in the May 2010 edition of Biocycle magazine. “In this new era, dumping stuff may cease to be an option because that stuff has value. and that value can be efficiently extracted for costs that are comparable to or lower than the costs — both environmental and monetary — associated with dumping.”

The San Francisco Board of Supervisors will vote on the contract later this year, deciding whether to validate the Department of the Environment’s choice of Recology or go with WM. Either way, lawsuits are likely to follow.