tredmond@sfbg.com

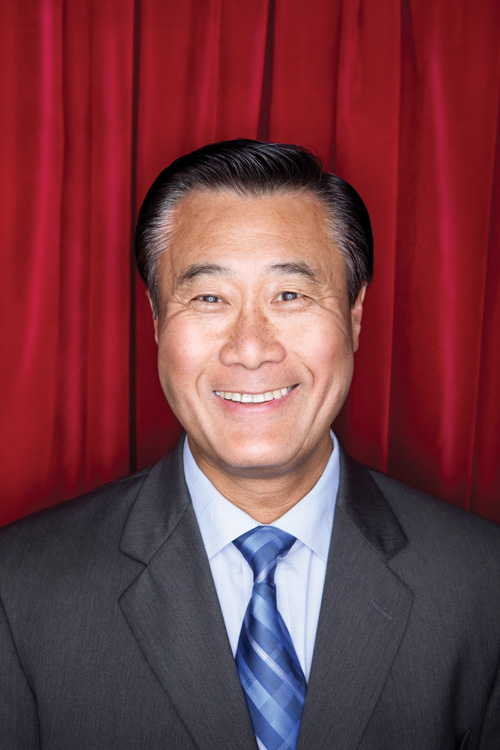

It’s early January 2011, and the Four Seas restaurant at Grant and Clay is packed. Everyone who is anyone in Chinatown is there — and for good reason. In a few days, the Board of Supervisors is expected to appoint the city’s first Asian mayor.

The rally is billed as a statement of support for Ed Lee, the mild-mannered bureaucrat and reluctant mayoral hopeful. But that’s not the entire — or even, perhaps, the central — agenda.

Rose Pak, who describes herself as a consultant to the Chinese Chamber of Commerce but who is more widely known as a Chinatown powerbroker, is the host of the event. She stands in front of the room, takes the microphone, and, in Cantonese, delivers a remarkable political speech.

According to people in the audience, she says, in essence, that the community has come out to celebrate and support Ed Lee — but that’s just the start. She also urges them not just to promote their candidate — but to do everything possible to prevent Leland Yee from becoming mayor.

She continues on for several minutes, lambasting Yee, the state Senator who lived in Chinatown as a child, accusing him of about every possible political sin — and turning the Lee rally into an anti-Yee crusade. And nobody in the crowd seems terribly surprised.

Across Chinatown, from the liberal nonprofits to the conservative Chamber of Commerce, there’s a palpable fear and distrust of the man who for years has been among San Francisco’s most prominent Asian politicians — and who, had Lee not changed his mind and decided to run for a full term this fall, was the odds-on favorite to become the city’s first elected Chinese mayor.

The reasons for that fear are complex and say a lot about the changing politics of Asian San Francisco, the power structure of a city where an old political machine is making a bold bid to recover its lucrative clout — and about the career of Yee himself.

Senator Leland Yee is a political puzzle. He’s a Chinese immigrant who has built a political base almost entirely outside of the traditional Chinatown community. He’s a politician who once represented a deeply conservative district, opposed tenant protections, voted against transgender health benefits and sided with Pacific Gas and Electric Co. on key environmental issues — and now has the support of some of the most progressive organizations in the city. He’s taken large sums of campaign money from some of the worst polluters in California, but gets high marks from the Sierra Club.

His roots are as a fiscal conservative — yet he’s been the only Democrat in Sacramento to reject budget compromises on the grounds that they required too many spending cuts.

He’s grown, changed, and developed his positions over time. Or he’s become an expert at political pandering, telling every group exactly what it wants to hear. He’s the best chance progressives have of keeping the corrupt old political machine out of City Hall — or he’s a chameleon who will be a nightmare for progressive San Francisco.

Or maybe he’s a little bit of all of that.

Leland Yin Yee was born in Taishan, a city in China’s Guangdong province on the South China Sea. The year was 1948; Mao Zedong’s Communist Party of China had taken control of much of the countryside and was moving rapidly to take the major cities. The nationalist army of General Chiang Kai-Shek was falling apart, and Yee’s father, who owned a store, decided it was time for the family to leave.

The Yees made it to Hong Kong, and since Mee G. Yee had previously lived in the United States and served in the U.S. Army during World War II, he was ultimately able to move the family to San Francisco. In 1951, the three-year-old Leland Yee arrived in Chinatown.

For four years, Yee lived with his sister and mother in a one-room apartment with a shared bathroom while his father worked as a sailor in the merchant marine. It was, Yee recalled in a recent interview, a tight, closed, and largely self-sufficient community.

“The movie theater, the shoe store, the barber shop, food — everything you needed you could get in Chinatown,” Yee said. “You never had to leave.”

Of course, after a while, Yee and his mom started to venture out, down Stockton Street to Market, where they’d shop at the Emporium, the venerable department store. “It was like walking into a different country,” he said. “If you didn’t know English, they didn’t have time for you.”

Yee, like a lot of young Chinese immigrants of his era, put much of his time into his studies — in the San Francisco public schools and in a local Chinese school. “My mom spoke a village dialect, and we had to learn Cantonese,” he said. “Every little kid had to go to Chinese school. We hated it.”

When Yee was eight, his parents managed to buy a four-unit building on Dolores Street, and the family moved to the Mission, where he would spend not only the rest of his childhood but much of his early adult life. He graduated from Mission High School, enrolled in City College, studied psychology and after two years won admission to UC Berkeley.

Berkeley in 1968 was a very different world from Chinatown and even the relatively controlled environment he’d experienced at home in the Mission. “You didn’t protest in school. You’d have been sent home, and your mother would kill you,” he said.

At Berekely, all hell was breaking loose, with the antiwar protests, the People’s Park demonstrations, the campaign to create a Third World College (which led to the first Ethnic Studies Department), and a general attitude of mistrust for authority. “I developed a sense of activism,” Yee said. “I realized I could speak out.”

That spirit quickly vanished when Yee lost faith in some of his fellow activists. “People would work with us, then get into positions of power and use that against you,” he recalled. “A lot of my friends said ‘forget it.’ I left the scene.”

Yee once again devoted his energy to school, earning a masters at San Francisco State University and a Ph.D in child psychology from the University of Hawaii. Along the way, he met his wife, Maxine.

With his new degree, the Yees moved back to San Francisco — and back in with his parents at the Dolores property, where he, Maxine and a family that would grow to four kids would live for more than a decade.

Yee worked as a child psychologist for the San Francisco Department of Public Health, starting the city’s first high school mental-health clinic. He went on to become a child psychologist at the Oakland Unified School District, then joined a nonprofit mental health program in San Jose.

In 1986, Yee decided to get active in politics for the first time since college, and ran for the San Francisco School Board. He lost — and that would be the only election he would ever lose. In 1988, he won a seat, and established himself as an advocate for students of color, fighting school closures in minority neighborhoods. He also tried to get the district to modify its harsh disciplinary rules, arguing against mandatory expulsions.

On fiscal issues, though, Yee was a conservative. For his first term, despite the brutal cutbacks of the recession of the late 1980s and early 1990s, he insisted that the district make do with the money it had. His solution to the red ink: Cut waste. Only in 1992, when he was up for re-election, did he acknowledge that the district needed more cash; at that point, he supported a statewide initiative to tax the rich to bring money to the schools.

The sense of fiscal conservatism — of holding the line on taxes, but mandating open and fair contracting procedures and tight financial controls — was a hallmark of much of his political career. When the Guardian endorsed him for re-election to the board in 1992, we wrote that “there’s real value in his continuing vigilance against administrative fat and favoritism in contracts.”

Over the next four years, Yee worked with then-Superintendent Waldemar “Bill” Rojas, a deeply polarizing figure who pushed his own personal theory of “reconstitution” — firing all the staff at low-performing schools — and later was enmeshed in a scandal that led to prison time for a contractor he’d hired. Yee told me he was the only board member to vote against hiring Rojas, but people who were watching the board closely back then say he didn’t always stand up to the superintendent.

He also became what some say was a bit too close with Tim Tronson, a consultant hired by the district as a $1,000-a-day facilities consultant. Tronson wound up getting indicted on 22 counts of grand theft, embezzlement, and conspiracy in a scheme to steal $850,000 from the schools, and was sentenced to four years in state prison.

In 1998, when some school board members wanted to build housing for teachers on property that the district owned in the Sunset, Yee led the opposition — with Tronson’s help. At one meeting at Sunset Elementary School, Yee went so far as to say, according to people present, that “Tim Tronson is my man, and I rely on him for advice.”

Yee acknowledged that he worked closely with Tronson to defeat that housing project. “He was the facilities manager,” Yee explained, “and I said that I trusted his judgment.”

Yee has either a great sense of political timing or exceptional luck. He ran for the Board of Supervisors in 1996, facing one of the weakest fields in modern San Francisco history. He was the only Chinese candidate and one of just two Asians (the other, appointed incumbent Michael Yaki, barely squeaked to re-election). In an at at-large election with the top five winning seats, Yee came in third, with 103,000 votes.

He was never a progressive supervisor. In 2000, the Guardian ranked the good votes of what we referred to as Willie Brown’s Board, and Yee scored only 43 percent. He was against campaign finance reform. He supported the brutal gentrification and community displacement represented by the Bryant Square development. He voted to kill a public-power feasibility study and opposed the Municipal Utility District initiative. He opposed a moratorium on uncontrolled live-work development.

In 2002, Yee was one of only three supervisors to oppose Proposition D, a crucial public-power measure that would have broken up PG&E’s monopoly in the city. He stood with PG&E (and then-Sups. Tony Hall and Gavin Newsom) in opposition to the measure, then signed a pro-PG&E ballot argument packed with PG&E lies.

When I asked him about that stand, Yee at first didn’t recall opposing Prop. D, but then said he “stood with labor” on the issue. In fact, the progressive unions didn’t oppose Prop. D at all; the opposition was led by PG&E’s house union, IBEW Local 1245.

Yee was particularly bad on tenant issues. He not only voted to deny city funding for the Eviction Defense Collaborative, which helped low-income tenants fight evictions; he actually tried to get the city to put up money for a free legal fund to help landlords evict their tenants. He opposed a ballot measure limiting condo conversions. He opposed a measure to limit the ability of landlords to pass improvement costs on to their tenants.

In 2001, Yee voted to uphold a Willie Brown veto of legislation to limit tenancies in common, a backdoor way to get around the city’s condo conversion ordinance. Only Hall and Newsom, then the most conservative supervisors on the board, joined Yee. At one point, he started asking whether the city should consider repealing rent control.

He opposed an affordable housing bond in 2002, joining the big landlord groups in arguing that it would raise property taxes. Every tenant group in town supported the measure, Proposition B; every landlord group opposed it.

I asked Yee about his tenant record, and he told me that he now supports rent control. But he said that he was always on the side of homeowners and small landlords, and that property ownership was central to Chinese culture. “I was responding to the Chinese community and the West Side,” he said.

He wasn’t much of an environmentalist, either — at least not in today’s terms. He was one of the only city officials to support a “Critical Car” rally in 1999, aimed at promoting the rights of vehicle drivers (and by implication, criticizing Critical Mass and the bicycle movement).

His record on LGBT issues was mixed. While he supported a counseling program for queer youth when he was on the school board, he also supported JROTC, angering queer leaders who didn’t want a program in the public schools run by, and used as a recruiting tool for, the military, which at that point open discriminated against gay and lesbian people.

Yee was also one of only two supervisors who voted in 2001 against extending city health benefits to transgender employees.

That was a dramatic moment in local politics. Nine votes were needed to pass the measure, and while eight of the supervisors were in favor, Yee and Hall balked. At one point, Board President Tom Ammiano had to direct the Sheriff’s Office to go roust Sup. Gerardo Sandoval, who was ducking the issue in his office, to provide the crucial ninth vote.

Yee didn’t just vote against the bill. According to one reliable source who was there at the time, Yee spoke to a community meeting out on Ulloa Street in the Sunset and berated his colleagues, quipping that the city should have better things to do than “spend taxpayer money on sex-change operations.”

It was a bit shocking to trans people — Yee had, over the years, befriended some of the most marginalized members of what was already a marginalized community. “There was one person at the rail crying, saying ‘Leland, how could you do this to us,'” Ammiano recalled.

The LGBT community was furious with Yee. “I didn’t speak to him for at least a year,” Gabriel Haaland, one of the city’s most prominent transgender activists, told me.

Yee now says the vote was a mistake — but at the time, he told me, he was under immense pressure. When he voted for the queer youth program, he said, “the elders of the Chinese community ripped me apart. They called my mother’s friends back in the village [where he was born] and said her son was embarrassing the Chinese community.”

That must have been difficult — and he said that “if I had known the pain I had caused, I wouldn’t have voted that way.” But it was hard to miss that pain his vote caused.

On the other hand, people learn from their experiences, attitudes evolve, we all grow up and get smarter, and the way Yee describes it, that’s what happened to him.

In 2006, when he was running for state Senate, Yee met with a group of trans leaders and formally — many now say sincerely — apologized. It was an important gesture that made a lot of his critics feel better about him.

“He didn’t have to do that,” Haaland said. “People change, and he paid for his crime, and that’s genuine enough for me.”

As a former school board member, Yee kept an interest in the schools — but not always a healthy one. At one point, he actually proposed splitting SFUSD into two districts, one on the (poorer) east side of town and one on the (richer) west. “We strongly opposed that,” recalled Margaret Brodkin, who at the time ran Coleman Advocates for Children and Youth. “Eventually he dropped the idea.”

For all the problems, in his time on the Board of Supervisors, Yee developed a reputation for independence from the Brown Machine, which utterly dominated much of city politics in the late 1990s. His weak 43 percent rating on the Guardian scorecard was actually third-best among the supervisors, after Ammiano and the late Sue Bierman.

In 1998, he was one of the leaders in a battle to prevent the owners of Sutro Tower from defying the city’s zoning administrator and placing hundreds of new antennas on Sutro Tower. He, Bierman, and Ammiano were the only supervisors opposing Brown’s crackdown on homeless people in Union Square.

When he ran in the first district elections, in 2000, against two opponents who had Brown’s support and big downtown money, the Guardian endorsed him, noting that while he “can’t be counted on to support worthy legislation … He’s one of only two board members who regularly buck the mayor on the big issues.”

(He never liked district elections, and used to take any opportunity to denounce the system, at times forcing Ammiano to use his position as president to tell Yee to quit dissing the electoral process and get to the point of his speech.)

In 2002, the westside state Assembly district seat opened up, and both Yee and his former school board colleague Dan Kelly ran in the Democratic primary. Yee won, and went on to win the general election with only token opposition.

His legislative record in the Assembly wasn’t terribly distinguished. Yee never chaired a policy committee — although he did win a leadership post as speaker pro tem. And he cast some surprisingly bad votes.

In 2003, for example, then-Assemblymember Mark Leno introduced a bill that would have exempted single-room occupancy hotels from the Ellis Act, which allows landlords to evict tenants for no reason. Yee refused to vote for the bill. Leno was furious — he was one vote short of a majority and Yee’s position would have doomed the bill. At the last minute, a conservative Republican who had grown up in an SRO hotel voted in favor.

When he ran for re-election in 2004, we noted: “What’s Leland Yee doing up in Sacramento? We can’t figure it out — and neither, as far as we can tell, can his colleagues or constituents. He’s introduced almost no significant bills — compared, for example, to Assemblymember Mark Leno’s record, Yee’s is an embarrassment. The only high-profile thing he’s done in the past several years is introduce a bill to urge state and local governments to allow feng shui principles in building codes.”

In 2006, Yee decided to move up to the state Senate, and he won handily, beating a weak opponent (San Mateo County Supervisor and former San Francisco cop Mike Nevin) by almost 2-1. His productivity increased significantly in the upper chamber — and in some ways, he moved to the left. He’s begun to support taxes — particularly, an oil severance tax — and when I’ve questioned him, he somewhat grudgingly admits that Prop. 13 deserves review.

He’s done some awful stuff, like trying to sell off the Cow Palace land to private developers. But he has consistently been one of the best voices in the Legislature on open government, and that’s brought him some national attention.

Yee has been a harsh critic of spending practices and secrecy at the University of California, and when UC Stanislaus refused in 2010 to release the documents that would show how much the school was paying Sarah Palin to speak at a fundraiser, Leland flew into action. He not only blasted the university and introduced legislation to force university foundations to abide by sunshine laws; he worked with two Stanislaus students who had found the contract in a dumpster and made headlines all over the country.

He’s fought for student free speech rights and this year pushed a bill mandating that corporations that get tax breaks for job creation prove that they’ve actually created jobs — or pay the tax money back. He’s also won immense plaudits from youth advocates and criminal justice reformers for his bill that would end life-without-parole sentences for offenders under 18.

Along the way, he compiled a 100 percent voting record from the major labor unions, including the California Nurses Association and SEIU, and with the Sierra Club. All three organizations have endorsed him for mayor.

Yee told me that he thinks he’s become more progressive over the years. “My philosophy has shifted,” he said.

Yet when you talk to his colleagues in Sacramento, including Democrats, they aren’t always happy with him. Yee has a tendency to be a bit of a loner — he’s never chaired a policy committee and in some of the most bitter budget fights, he’s refused to go along with the Democratic majority. Yee insists that he’s taken principled stands, declining to vote for budget bills that include deep service cuts. But the reality in Sacramento is that budget bills have until this year required a two-thirds vote, meaning two or three Republicans have had to accept the deal — and losing a Democratic vote has its cost.

“You have to give up all sorts of things, make terrible compromises, to get even two Republicans,” one legislative insider told me. “When a Democrat goes south, you have to find another Republican, and give up even more.”

In other words: It’s easy to take a principled stand, and make a lot of liberal constituencies happy, when you aren’t really trying to make the state budget work.

I met Rose Pak on a July afternoon at the Chinatown Hilton. She brought along her own loose tea, in a paper package; the waitress, who clearly knew the drill, took it back to the kitchen to brew. Pak and I have not been on the greatest of terms; she’s called the Guardian all kinds of names, and I’ve had my share of critical things to say about her. But on this day, she was polite and even at times charming.

After we got the niceties out of the way (she told me I was unfair to her, and I told her I didn’t like the way she and Willie Brown played politics), we started talking about Yee. And Pak (unlike some people I interviewed for this story) was happy to speak on the record.

She told me Yee had “no moral character.” She told me she couldn’t trust him. She told me a lot of stories and made a lot of allegations that we both knew neither she nor I could ever prove.

Then we got to talking about the politics of Chinatown and Asians in San Francisco, and a lot of the animosity toward Yee became more clear.

For decades, Chinatown and the institutions and people who live and work there have been the political center of the Chinese community. Nonprofits like the Chinatown Community Development Center have trained several generations of community organizers and leaders. The Chinese Chamber of Commerce, the Six Companies, and other business groups have represented the interests of Chinese merchants. And while the various players don’t always get along, there’s a sense of shared political culture.

“In Chinatown,” Gordon Chin, CCDC’s director, likes to say, “it’s all about personal connections.”

There’s a lively infrastructure of community-service programs, some of which get city money. There’s also a sense that any mayor or supervisor who wants to work with the Chinese community needs to at least touch base with the Chinatown establishment.

Yee doesn’t do that. “He doesn’t give a shit about them,” David Looman, a political consultant who has worked with many Chinese candidates over the years, told me.

Yee’s Asian political base is outside of Chinatown; he told me he sees himself representing more of the Chinese population of the Sunset and Richmond and the growing Asian community in Visitacion Valley and Bayview.

Pak is connected closely to Brown, who Yee often clashed with. For Pak, Brown, and their allies, strong connections to City Hall mean lucrative lobbying deals and public attention to the needs of Chinatown businesses. Then there’s the nonprofit sector.

CCDC and other nonprofits do important, sometimes crucial work, building and maintaining affordable housing, taking care of seniors, fighting for workers rights, and protecting the community safety net. Yee, Pak said, “has never shown any interest in our local nonprofits. We all work together here, and he doesn’t seem to care what we do.” Yee told me he has no desire to see funding cut for any critical social services in any part of town. But he has also made no secret of the fact that he questions the current model of delivering city services through a large network of nonprofits, some of which get millions of taxpayer dollars. And the way Pak sees it, all of that — the nonprofits, the business benefits, the contracts — are all at risk. “If Leland Yee is elected mayor,” she told me, “we are all dead.”

I ran into an old San Francisco political figure the other day, a man who has been around since the 1970s, inside and outside of City Hall, who remains an astute observer of the players and the power relationships in the local scene. At the time we talked, he wasn’t supporting any of the mayoral candidates, but he had a thought for me. “This town,” he said, “is being taken over by a syndicate. Willie Brown is the CEO, and Rose Pak is the COO, and it’s all about money and influence.”

That’s not a pleasant thought — I’ve lived through the era of political machine dominance in this town, and it was awful. In the days when Brown ran San Francisco, politics was a tightly controlled operation; only a small number of people managed to get elected to office without the support of the machine. Developers made land-use policy; gentrification and displacement were rampant; corruption at City Hall turned a lot of San Franciscans off, not only to the political process but to the whole notion that government could be a positive force in society.

A few years ago, I thought those days were over — and to a certain extent, district elections will always make machine politics more difficult. But when I see signs of the syndicate popping up — and I see a candidate like Ed Lee, who’s close friends with Brown, leading the Mayor’s Race — it makes me nervous. And for all his obvious flaws, at least Leland Yee isn’t part of that particular operation. If there’s a better reason to vote for him, I don’t know what it is.

YEE HOME PURCHASE RAISES SUSPICIONS

Rose Pak has a question about Leland Yee. “How,” she asked me, “did the guy manage to buy a million-dollar house on a $30,000 City Hall salary?”

Pak isn’t the only one asking — numerous media reports over the years have examined how Yee raised a family of four and bought a house in the Sunset on very little visible income. And while I’m not usually that interested in the personal finances of political candidates, I decided that it was worth a look.

Here’s what I found: Public records show that in July 1999, Yee and his wife, Maxine, purchased a house on 24th Avenue for $875,000 (it’s now assessed at slightly more than $1 million). At the time, Yee was a San Francisco supervisor, earning a little more than $30,000 a year. (The salary of the supervisors was raised dramatically shortly after Yee left the board and went to the state Assembly.) His wife wasn’t working. And his economic interest statements for that period show no other outside earnings. So the disposable, after-tax income of the entire Yee family couldn’t have been much more than $25,000.

That, by any normal standard, shouldn’t have been enough to float a mortgage that, records show, totaled $516,000. In fact, the interest payments alone on that mortgage alone would total $3,600 a month — more than Yee’s gross income.

Documents in the Assessor’s Office show another paper trail, too. In 1989, Jung H. Lee, Yee’s mother, transferred the deed on a four-unit Dolores St. building where the family had been living to Maxine and Leland Yee — for no money. And a few months before the Yees bought the Sunset house, they took out a $320,000 home-equity loan on that property. That was the down payment on the Sunset property.

Still: At that point, the Yees would have been paying off two mortgages, with a total nut of about $5,000 a month — and supporting four kids, in San Francisco. In 2002, Yee’s economic interest statement’s show some modest income from teaching at Lincoln University — but nowhere near enough to pay that level of expenses.

What happened? Yee explains it this way: “For more than 10 years, we were living rent-free in my parents’ property,” he told me I an interview. “We were a close Chinese family, and my parents provided the food and helped pay for the children’s clothing. So we had almost no expenses and we lived very frugally.”

During that period, Yee was working for the San Francisco Department of Public Health, the Oakland Unified School District, and a San Jose nonprofit, earning, he said, between $50,000 and $90,000 a year. If he saved almost all of that money, he would have had more than a half-million dollars in the bank when he bought the Sunset house.

There’s nothing on any of his economic disclosure forms showing any ownership of stocks or other reportable financial interests during that period, so he wasn’t investing the money. In fact, he says, it was, and is, all in simple savings accounts. A bit unusual for that large a sum of money.

How did he get a mortgage? “Back then,” he said, “banks were willing to lend a lot more freely than they do today.”

Starting in 2003, Yee was in the state Assembly, making a higher salary — but still not much in excess of $100,000 a year. After taxes, he was probably taking home about $75,000 — and $60,000 was going to the two mortgages.

How did he do it? “We have been supplementing our income with our savings,” he said. “We don’t take vacations, we are very careful with our money.” And they clearly aren’t desperate for cash — Yee’s daughter occupies two of the four units in the Dolores St. building they own, but the other two units are vacant.

It’s possible. It’s plausible. But I don’t blame people for wondering how he managed to pull it off. (Tim Redmond, with research assistance by Oona Robertson)

BIG CORPORATIONS HAVE BACKED YEE

Yee became a prodigious fundraiser in Sacramento — and a lot of the money came from big corporations that had business in the Legislature. And while he has perfect scores from the Sierra Club and the big labor unions, he’s taken tens of thousands of dollars from some of the biggest corporations, agribusiness interests, and polluters in the state. And at times, he’s voted their way.

Since 1993, for example, campaign finance records show Yee has taken more than $20,000 from Chevron, ExxonMobil, Valero, Conoco Phillips, and BP. He’s received another $22,450 from the chemical industry (and industry employees). Most of it came from Clorox, Dow Chemical, and Dupont.

And while the Sierra Club may not have considered it a priority, Sen. Mark Leno has worked hard to pass a bill limiting chemical fire retardants in furniture. In 2008, Yee voted against Leno’s AB 706.

That year he also refused to support a bill that would prohibit the use of the chemical diacetyl in workplaces. The industries that opposed AB 514 (including Bayer, Abbott Laboratories, Pfizer, and Johnson & Johnson) have given Yee a total of more than $60,000.

In 2003, Yee voted against a crucial tenant bill, one that would have prevented the owners of single room occupancy hotels from using the Ellis Act to evict tenants. He received a campaign check for $2,500 from the San Francisco Apartment Association the next day. Landlords in general have given Yee close to $40,000.

Then there’s agribusiness. Yee gets a lot of money from the farming industry, despite the fact that there obviously aren’t many farms in his district. Why, for example, would the California Poultry Association, the California Cattlemen’s Association, and the California Farm Bureau give him money? The Poultry Association’s Bill Mattos told us that Yee “has taken a keen interest in California’s poultry industry.”

Yee also took immense flak from the San Francisco Chronicle and other papers over a 2003 vote against a bill to limit emissions from farm vehicles. In an editorial, the paper wrote that he was “doing dirty work for the lobbyists.” In the end, under immense public pressure, he switched positions and voted for the bill. I asked Yee about all that money from all those bad operators, and he told me — as most politicians will — that campaign cash has never influenced any of his votes.

So why do all these groups give him money? “It’s about whether you will sit down and listen,” Yee said. “I will talk to all sides and at least consider the arguments as a thoughtful human being. Then I vote my conscience.” (Tim Redmond, with research by Oona Robertson)