Follow the Guardian’s complete Occupy SF coverage here.

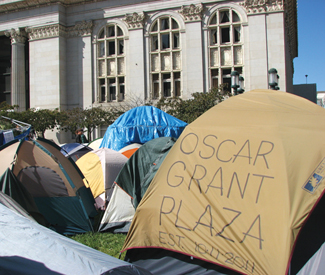

Thursday morning, in gray seven o’clock fog, about 100 people asleep in front of the Federal Reserve building began to blink their eyes open. The bustling camp that had been there the day before — a small village of tents, tarps and easy-ups, shelves brimming with books, art supplies, and a display of hundreds of signs — was gone. The kitchen and all their food were missing, too.

“Wake up, everyone’s gotta wake up. Remember, sit/lie kicks in at seven,” urged a few protesters gently, winding their way through the maze of sleeping bags and blankets. No one was in the mood for legal trouble. All the people there, and a few hundred more who had gone home at two and three in the morning, had been a part of OccupySF’s first clash with the police. Someone pushed a cart full of fruit and granola bars. Breakfast. It was the camp’s first food donation since the incident, which had ended only four hours before. In the calm morning air, it was clear: the police could confiscate gear, but they could not stop the protest. It was only the beginning.

To say that OccupySF has grown in the past three weeks does not begin to describe it.

On Wednesday, Oct. 5, the camp was busy, clean, and what organizer Amy O proudly described as “jubilant.” Hundreds exchanged ideas, played music, and made signs and art. Two abundant snack tables providing free food to any and all were only the tip of the iceberg; the kitchen was piled so high that organizers had begun turning away food donations.

This scene contrasted starkly to the demonstration’s first night. Occupy SF started on Sept. 17, the same day as Occupy Wall Street, as one of the solidarity actions now reportedly numbering over 1,000. About 150 people gathered for the protest that first day and only a handful stayed the night. A week later, there was a devoted group of 10 campers. By Oct. 1, a good 40 people were camping and the kitchen and communications sections were set up. When the police showed up late Wednesday night, camp was 200 strong.

AS LONG AS IT TAKES

Spending time at the camp is addictive. Since my first night, I feel something constantly pulling me back. That night, Oct. 1, the camp was lively and half a block long. A big, hot pot of soup sat on the kitchen stove. Next door, the communications area was populated with organizers busily typing on laptops. The medical tent was next, kept pristine but as of yet untouched—its necessity, nonetheless, was evident after that week’s incident in New York when police pepper sprayed a group of young women.

At that point, the San Francisco Police Department had been courteous with OccupySF. They provided escorts on marches and didn’t bother the camp. Soon after arriving, Russell, a friendly 23-year-old from San Diego who has been camping since the first day, greeted me. He told me that there was a Gardening Committee meeting in a few minutes, and I planned to check it out. Next I saw Lesley Moore, 48, an Oakland resident with unrelenting energy and a knack for mediating misunderstandings at meetings.

She carried a clipboard and was compiling a massive list of food, supplies, and every imaginable resource the group might want. I learned that a flood of supporters, eager to donate, had requested info about what the camp needed. She planned to post the list on occupysf.com later that night.

Fifteen people climbed into a tent for the Gardening Committee meeting, keen to begin growing food for the camp. The donations were rolling in, and if there was a project we wanted to do, well, we probably could. We discussed what could grow in the winter and planting more in the spring. The mood was giddy with possibility but a bit uneasy— could we imagine we’d still be here then?

Many participants are determined to stay put. Jreds, a protester who had come from Chico, looked me in the eye and promised, “I’m staying as long as it takes.”

When asked his occupation, Jreds replied, “This is our occupation.”

After years of foreclosures and unemployment, no wonder so many people are motivated and available to work and sleep at a place like this. Wall Street’s unmitigated power has failed to trickle down into economic opportunities for the rest of us, and in this economy, “why don’t you just get a job” is starting to sound like “let them eat cake.”

As John Reimann, 65, a retired carpenter from Oakland, put it, “I’ve been waiting 10 years for something like this.” He helped start Occupy Oakland last week.

Protester Chris L, who says the community at the camp is the best part about it, also plans to stay indefinitely. Billy Gene Hobbs, a promoter from LA who can often be seen jumping and shouting to keep protest crowds pumped, came to visit San Francisco two weeks ago, found the camp, and hasn’t left. Since the police came through, almost 100 more people have joined.

The camp’s population is a source of ongoing discussion. Complaints of “too many hippies” usually die quickly when someone actually comes to camp, where the people they’re referring to are not the only ones and, moreover, are active and responsible organizers.

Others object that the protest is populated mostly with young people, especially white and male. There is active discussion on how to accommodate people with children as well as people with disabilities.

It seems everyone — including the many people of color, folks of all ages, and disabled people who have been organizers and participants in the movement — shares the view that oppressive institutions work hand in hand with the corporate corruption and power that the movement strives to end.

THE PEOPLE’S MIC

Camp life is dotted with calls for the People’s Mic, a tool developed at Occupy Wall Street, where using bullhorn or speakers is illegal. When someone yells “Mic check!” the crowd echoes in response. The person speaks his piece, sentence by sentence, as the crowd repeats. If a few people nearby can hear him, everyone can. For better or for worse, it tends not to amplify ideas people don’t have much taste for; at a recent meeting, when someone insisted that people who had been foreclosed on were greedy and foolish, the People’s Mic’s volume faded fast.

The People’s Mic requires no electricity, discourages rambling, a brilliant improvisation. But the central feature of Occupations throughout the country is the General Assembly. OccupySF has been holding General Assemblies every day at camp at 6 p.m. and on Saturdays at noon in Union Square. In the past week they have consistently boasted a couple hundred participants daily, but continue to practice consensus-based decision-making and participatory democracy. They’re long and often frustrating, but for many, as a standard rallying cry insists, “This is what democracy looks like!”

Many have stepped up at meetings to say that too many men, too many white people, or simply too many of the same voices are being heard. Solidarity efforts like Occupy the Hood, which declares the vital need that people of color make decisions and organize in and along with the occupations, have surfaced nationally.

On Oct. 5, after about 700 people marched on the Financial District with OccupySF, the General Assembly was particularly well attended. It was peppered with invitations and expressions of solidarity, conveyed by representatives of groups from throughout the Bay Area.

The week’s schedule slowly filled: Thursday’s anti-war march, the next day’s teach-in with activist Miguel Robles, a 7 am “Wake Up Action” with Unite-HERE Local 2 on Oct. 10, and plans to coordinate with the LGBT rights group Get Equal for a National Coming Out Day action the next day.

Carolyn DeRoo, a brightly charismatic BART station agent, reveled in the whoops and cheers when she announced that Amalgamated Transit Union Local 1555, the union that represents BART workers, had just voted to endorse Occupy SF. “I got an hour off work today so I could be in the march,” said DeRoo.

She expressed concern over the lack of coherent messaging, hoping it wouldn’t hurt the movement. “I was about to get on a plane to New York because of how badly I wanted to be a part of it,” she said. “I’m so glad it has started in SF.”

THE COPS ARRIVE

But on that fateful night, Oct. 5, meeting ideals were strained. High-tension and often angry debate filled the hours between being warned of police action and its onset, making consensus difficult. Some wanted to take down the camp, unable to risk arrest. There were campers from all walks of life present, including some homeless folks and travelers who would risk losing all or most of their possessions if the police confiscated them. Others didn’t want to see the camp’s growth stunted due to police intimidation.

Dierdre Anglin, 40, an Oakland resident who works in the nonprofit sector, was particularly calm amongst the chaos. “I think the energy got a little high,” she said, as protesters ran around taking down tents and preparing for the imminent police confrontation. “But we have decided to take the stance and to stay here.”

She added, “I personally feel that they are not going to do anything because it would make the police look quite bad. There’s a lot of support for us.” Anglin’s prediction about the cops’ actions, if not their public relations consequences, was mistaken. Police marched in around 1 am, and Department of Public Works employees began to fill their trucks with camp materials.

Billy Gene, ever energetic, raced to lie down on the street in front of trucks and was dragged away, yelling “Don’t be mean!” at police. Many sat and stood in front of trucks. Others could be seen shaking their heads at colleagues’ verbal attacks and murmuring, “that isn’t nonviolent.”

There was no property damage or physical violence on the part of the protesters, although one man was arrested for allegedly punching an officer in the face, which both sides cast as an aberration that didn’t reflect the tenor of the standoff.

At 3 am, protesters surveyed the damage. An organizer addressed the group: “We’re still here, and it’s time to rebuild.” The camp received a donation of blankets and sleeping bags at four o’clock that morning. At five, a small jam session and dance party broke out.

Police have since provided information on how to retrieve confiscated materials, and Police Chief Greg Suhr told us they’ve been actively trying to facilitate getting people their stuff back and allowing the occupation to continue (see accompanying article for more from Suhr).

In the days since, the mood has again turned jubilant. On Thursday afternoon, Oct. 6, about 120 people were gathered at the camp. Signs ranged from “student loan debt is slavery” to “grannies against war.” The next night, the mass of people had increased, and with it the group’s creativity. Protesters could be seen pedaling a stationary bike connected to a battery, powering laptops.

As the sun set Friday, 300 people at camp looked west. They erupted in cheers as a 500-person anti-war demonstration marched onto the site. Market between Main and Embarcadero was shut down as protesters rallied and then held General Assembly. A dozen police lined up near the sidewalk; one told me they were separating OccupySF from the march. The next second, the “march” erupted in chants of “We are the 99 percent,” the Occupy movement’s signature rallying cry. Attempts to divide were futile.

That the movement has no “one message” has in many ways worked to their advantage. It seems hundreds of thousands of people with varying issues and concerns can all agree that an elite class, embodied by Wall Street, has far too much power and money, and that the people must unite against the sorry state of this system. As I looked in the officers’ eyes, I wondered how long even their disconnect from the protesters will last. Most are, after all, the 99 percent too.

After the General Assembly held the street for an hour, police requested that they please move to the sidewalk. A consensus vote decided to oblige. An assembly member proclaimed, words booming with the roar of the People’s Mic, “Let us remember that we took this street, and we could have held it if we wanted to.”

This is the kind of power many haven’t felt in a long time. And I get the feeling that no one intends to relinquish it any time soon.