steve@sfbg.com, joe@sfbg.com

San Francisco’s economy is booming these days, fueled by the latest dot-com bubble and a hot real estate market, sending more than expected tax revenue into city coffers. So why doesn’t San Francisco have a big budget surplus to help address the gentrification and displacement triggered by the boom?

The lack of satisfying answers to that question is adding to the populist political outrage that is now animating the city, from the regular street protests against evictions and rising income inequality to the corridors of City Hall, where labors leaders and progressive activists are calling for a repeal of the corporate welfare policies adopted by the Mayor’s Office.

The city’s charter-mandated, biannual Five Year Financial Plan Update, released March 6, shows projected annual city budget deficits growing steadily from $66.7 million in 2014-15 to $339.4 million in 2017-18, demonstrating that even the hottest of economies can’t overcome the city’s structural budget deficit.

Revenues are indeed growing, but not nearly as fast as the cost of running the city, a mismatch that has only been exacerbated by tens of millions of dollars in tax breaks given to Twitter and other growing companies along mid-Market Street and those that offer stock options.

Changing the business tax from a payroll to gross receipts tax also failed to address that structural deficit, and it may have even exacerbated it, particularly for the big tech firms that came out ahead in the switch. Bottom line: The city isn’t bringing in enough revenue to balance its bottom line, even in good years.

Last week, members and allies of the largest city employee union, Service Employees International Union Local 1021, stormed through City Hall demanding its share of the city’s wealth, promising to return this week when a delayed Board of Supervisors Budget and Finance Committee hearing will finally be held.

This year’s city budget process could emerge as a key narrative in the tale of two San Franciscos that is being told here and by watchers around the world.

ENOUGH IS ENOUGH

Nearly 300 SEIU members and their supporters protested the business tax breaks on the steps of City Hall on March 19, in advance of the scheduled budget hearing inside. Their chants took a unique twist on a familiar theme.

“Whose city?!” Sup. David Campos asked the crowd. “Everyone’s city!” they shouted back.

And that’s the rub. It’s not about excluding tech and corporations from San Francisco, the protesters said, it’s about fairness.

“There’s a great deal of wealth in San Francisco, and it’s wealth that leaves behind many of us,” Campos told the crowd of purple-clad protesters. “It’s time to put working people in front of the line.”

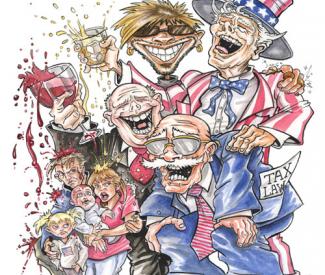

The giveaways to corporations and the tech industry are at a breaking point, the protesters said. Twitter alone is getting an estimated $56 million tax break, with millions more going to the companies in its orbit. The Google buses are only paying a dollar per stop, bringing in budgetary decimal dust from a corporation worth $390 billion. City taxpayers paid $5.5 million to subsidize Oracle CEO Larry Ellison’s America’s Cup last summer.

The numbers are adding up, and the union workers were asking how the city can give away hundreds of millions of dollars to the wealthy tech industry while the city struggles to provide basic services while bridging budget deficits. Mayor Ed Lee and his allies emphasize his economic policies stimulate the economy and create jobs, but the workers say that’s only increasing the cost of living here.

“I have a family of five and I couldn’t afford to stay here,” said Brandon Dawkins, an employee in the Department of Public Health. “I was born and raised in San Francisco and we had to move to Oakland. And now that’s expensive and we’re going to have to go to Sacramento and I’ll commute here for work.”

Tech-driven job creation doesn’t do anything for Dawkins. “I don’t know why they’re helping Twitter when they sure aren’t helping us,” he said.

And it’s not just about the money. SEIU Political Action Chair Alysabeth Alexander said tech titans turn a blind eye to workers when they defend their corporate shuttle program on environmental grounds.

“The companies using the shuttles often say that the shuttles move hundreds of cars off the road,” she told the crowd. But she cited studies showing housing prices increase around the shuttle stops, forcing displaced workers to commute into San Francisco so tech workers can have convenient, private transportation options.

“Safe and sustainable transportation should be available for everybody,” she shouted as the crowd erupted into a wave of cheers.

Companies like Google are beginning to help the city with its budget problems, recently donating $6.8 million to support the Free Muni For Youth program. San Francisco native Marc Benioff, the founder of Salesforce.com, is also calling on his tech brethren to do more. But the protesters were dubious about such calls to charity.

“Donations, first of all, are really skewed to whatever the corporate interests feel like funding. There’s not a fair and equal public policy [for where to spend], it’s all corporate driven. And ultimately the donations don’t make up anywhere near the amount they’ve gotten in terms of tax breaks,” said Mike Casey, president of UNITE HERE Local 2.

He’s describing the great donation swindle. The tech companies deprive the city of hundreds of millions of dollars in tax giveaways, then sprinkle a few million here and there to look like heroes, likely writing it off from their federal taxes anyway.

“They get a lot of good publicity, but they’re not paying their fair share,” Casey said.

SEIU pledges to continue pushing this narrative, announcing another big event at City Hall on Tax Day, April 15.

“If Twitter really feels like they’re part of the community, they should remit those tax breaks and give back that revenue,” SEIU spokesperson Carlos Rivera told the Guardian, sending a clear message that corporate welfare won’t be tolerated anymore. “We’re telling them those days are over.”

STRUCTURAL DEFICIT

City officials say the budget picture is better because of the economic boom than it otherwise would have been, and they credit the business tax breaks with helping that boom.

“We’re in better shape than we were a few months ago,” Controller’s Office Director of Budget and Analysis Michelle Allersma, one of three authors of the five-year budget projection, told the Guardian.

Revenues are up, but not as much as might be expected given the current boom and its costly byproducts. The city’s six-month budget report projects business taxes coming in at $534.7 million this year, rather than the $533 million budgeted. Property taxes are showing a $21.6 million increase over the budgeted $1.1 billion, sales taxes are showing a $2.7 million hike to $128.4 million, and the hotel tax is showing the biggest percentage jump, up $22 million over budget to a projected $296.9 million. But the parking and utility users taxes are together bringing in $3.1 million less than what was budgeted.

“The big picture from our perspective is we’re predicting significant revenue growth over the [next five-year] period, it’s just that the pace of our expenditures exceeds that growth,” Allersma said.

She said the biggest drivers of that expenditure growth are employee retirement expenses, lingering costs from the 2008 financial crisis, delayed infrastructure and maintenance costs, rebuilding depleted reserves, and one-time costs such as equipment for the new General Hospital.

Yet if the city can’t meet its obligations even in good years, doesn’t that mean the budget has a structural imbalance that it should address? Couldn’t the city have addressed that two years ago when Mayor Ed Lee crafted a business tax overhaul that was basically revenue-neutral, or now by ending tech’s tax exemptions?

“Thanks to sound economic policies and a strong rebounding economy, the City has avoided the deep cuts to social services we experienced in the past and we could even backfill for cuts to state and federal programs that serve low income families and people with HIV and AIDS,” Mayor’s Office Press Secretary Christine Falvey wrote in response to our list of questions about why the boom hasn’t created a budget surplus. “Business tax is significantly increased and in addition to social service programs, the City can now invest in capital projects and in paying down debt and increasing reserves. Unfortunately, our increase in revenues did not keep pace with the increases in City costs.”

The five-year budget report is a conservative one, as its authors describe it, with its first “key assumption” being “No major changes to service levels and number of employees,” even though the city is going through a big growth spurt, its skyline dotted with construction cranes. And for the employees serving that growth, it assumes only salary increases that keep pace with inflation.

But the report notes that the city could be in trouble if there’s a downturn in the tech industry. “Our city revenue is really volatile. When we do well, we do really well, and when we do bad, we do really bad. Tech is inherently volatile and tourism can quickly dry up,” Allersma told us.

Yet Falvey said the mayor plans to stay the course with his pro-business agenda. “Job creation remains key,” Falvey wrote to us. “The mayor continues to believe that there is no bigger income gap than between someone who has a job and someone who does not. As the budget is crafted over the next few months, the mayor will be meeting with a number of groups to make sure the budget reflects the needs of the city and that we close a deficit while providing the services people need.”

Brian McMahon contributed to this report.