Memorial services for Charles Lee Smith, a classic liberal activist whose hero was Tom Paine and whose passion was pamphleteering, will be held at 3 p.m. on Friday, Feb. 12, at the Friends Meeting House, Walnut and Vine, in Berkeley. He died at his Berkeley home on Jan. 7 at 84.

His wife Anne said that Charlie, as we all called him, fell in December and never fully recovered. She brought him home under hospice care on Jan. 5 and she and his two sons Greg and Jay were with him his last three days.

Charlie first contacted me in the early days of the Guardian in the late l960s. I soon realized that he was my kind of liberal, always working tirelessly, cheerfully, and quietly to make things better for people and their communities. He was a remarkable man with a remarkable range of interests and causes that he pursued his entire life.

He campaigned endlessly for causes ranging from the successful fight to stop Pacific Gas and Electric Co. from building a nuclear power plant on Bodega Bay to integrating the Berkeley schools to third brake lights for cars to one-way tolls on bridges to disaster preparedness to traffic safety and circles to public power and keep tabs on PG@E and big business shenanigans.

When he first began sending tips our way, he was working with, among many others, UC Berkeley Professor Paul Taylor with his battles with the agribusiness interests. He was helping UC Berkeley professor Joe Neilands on his public power campaigns. I remember a key public power meeting that Joe and Charlie put together in a Berkeley restaurant. It brought together the sturdy public power advocates of that era. Charlie did much of the staff work and was seated at the speaker’s table next to the sign that read, Public Power Users Association.

I credit that event and its assemblage of public power activists as inspiring the Guardian to make public power and kicking PG@E out of City Halls a major crusade that continues to this day. Charlie and Joe rounded up, among others, then CPUC commissioner Bill Bennett, consumer writer Jennifer Cross, William Domhoff, the UC Santa Cruz political science professor who was the main speaker, and Peter Petrakis, a student of Neilands’ in biochemistry who researched and wrote the Guardian’s early pioneering stories on the PG@E/Raker Act scandal. (See Guardian stories and editorials since l969.) The room was also full of veteran public power warriors from PG@E battles in Berkeley, San Francisco, and around the bay.

Charlie was a lifelong volunteer for the Quakers and pamphleteered on many of their projects.

My favorite story was how he was helping Dr. Ben Yellen, a feisty liberal pamphleteer in Brawley. Yellen and Charlie were political and pamphleteering soulmates, but Charlie was operating in liberal Berkeley and Yellen was in very conservative Imperial County.

Yellen was blasting away at the absentee land owners who were cheating migrant laborers on health care, on high private power costs of city dwellers, and the misuse of government water subsidies. And so he had trouble getting his leaflets printed in Brawley. He would send leaflets up to Charlie and Charlie would get them duplicated and then send the copies back to Yellen. Yellen would distribute them, mimeographed material on legal-sized yellow construction paper, under windshield wipers during the early morning hours and into open car windows on hot afternoons.

Charlie relished promoting Yellen as a classic in the world of pamphleteering and loved to talk about how Yellen followed up his pamphleteering with several pro per lawsuits, an appearance on CBS’ 60 Minutes television show, and a case that went to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Charlie liked to talk about his triple play of information distribution. He pamphleteered on street corners, prepared more than 50 bibliographies of undiscussed issues (including the best bibliography ever done on San Francisco’s Raker Act Scandal), and circulated his personal essays and cut and pasted newspaper articles. Almost every day, he would take the newspapers from the sidewalk near his house and put them on the front porches of his neighbors. He got some exercise, since his house was on a Berkeley hill, and he endeared himself to his neighbors. He was given the title of “Mayor of San Mateo Road.”

Charlie pamphleteered on more than l50 “undiscussed subjects,” as he called them, in Berkeley, Oakland and San Francisco. He sometimes went out to Palo Alto, Santa Rosa, and Napa, with occasional excursions to Boston and London. His subjects were practical and straightforward but breathtaking in their range: humanizing bureaucracy, employee suggestions, penal reform, illiteracy, migant labor, water, energy, land reform, ombudsmen, coop issues, library use, land value taxation, transportation, disaster recovery planning. He handed out KPFA folios and an occasional Bay Guardian.

He often combined pamphleteering with doing bibliographies to spread the word about the undiscussed subjects. On the first Earth Day in l970 at California State University, Hayward, Charlie spoke about the evils of automoblies. Then he distributed his bibliography of the Automobile Bureaucracy. In recognizable Charliese, he produced a blizzard of numbered citations on a summary of his speech so the audience could read further on his issues.

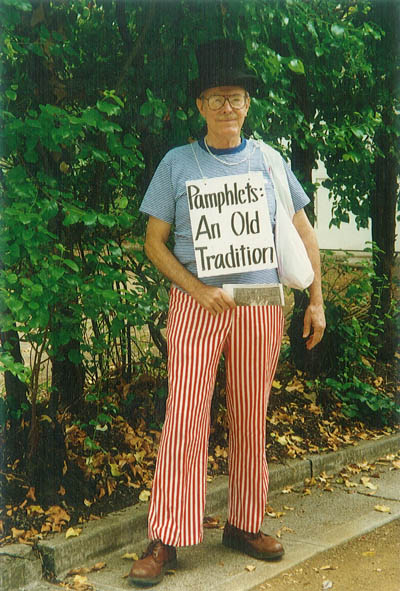

He considered pamphleteering as a noble form of communication that “went on during the colonial Period for a l00 years before the revolution and the arrival of Tom Paine in l775,” as he put it in his own pamphlet, “Pamphleteering: an old tradition.” He wrote that his main contribution “is the novel use of sandwich boards to screen out the disinterested while reaching the already-interested and open-minded persons with leaflets on the street, but not invading anyone’s privacy.”

Sometimes, Charlie had news close to home.

He said that giving out pamphlets to one or two people at a time was like holding a meeting with those persons and thus it was possible to have a “meeting” with several hundred people nearly anywhere within reasonable limits. He concluded that pamphleteering was “basic to building support for worthwhile projects” and claimes that it “may even be more effective than other forms of expensive communication.”

Charlie knew how to work the streets, but he also knew how to work inside the bowels of the bureaucracy. He worked for the California Division of Highways (now Caltrans) from l953 to 1987, mostly in an Oak Street office in San Francisco. I admit when Charlie talked to me about fighting bureaucracy, as he often did, I had trouble understanding how he was going about it. But Charlie had his ways.

Executive Editor Tim Redmond recalls that Charlie worked for Caltrans back in the days when the very thought there might be transportation modes other than highways was heresy.

He was an advocate of bicycles, carpools and public transit and Redmond thought that, when he first met Charlie in l984, “he must be like the monks in the middle ages, huddled in a corner trying to preserve knowledge. Nobody else at Caltrans wanted to talk about getting cars off the roads. Nobody wanted to shift spending priorities. Nobody wanted to point out that highrise development in San Francisco was causing traffic problems all over the Bay Area–and that the answer was slower development, not more highways.

“But Charlie said all those things. He told me where the secrets of Caltrans were hidden, what those dense environmental impact reports really showed, and how the agency was failing the public. I had a special card in my old l980s Rolodex labeled ‘Caltrans: Inside Source.’ The number went directly to Smith’s desk.” Charlie usually carpooled from Berkeley to his San Francisco office.

Charlie wrote a leaflet about the “Work Improvement Program” that then Gov. Pat Brown instituted in l960. It was, he wrote, a “novel program to get all state employees to submit ideas to improve their work.” Charlie labeled it “corrupt” and laid out the damning evidence. No appeal procedure. No protection for the employee making suggestions that the supervisor or organization didn’t want to use. No requirement for giving the employee credit for the idea or for following up the idea.

Charlie noted that he was a generalist with lots of ideas, read lots of publications, and was “sensitive to the problems that bother people.” He noted that there were l,500 employees in his Caltrans district who submitted 236 suggestions. Charlie submitted 35 of them. But, he noted wryly, “my supervisor, Charles Nordfelt, did not respond at all to any of my suggestions.” And then, to make neatly make his point, Charlie listed a few of his suggestions, all of them practical and useful.

Many were adopted without Charlie ever getting credit. Others were adopted decades later. For example, he pushed the then-heretical idea of collecting tolls on a one-way basis only, instead of collecting them two ways. He noted that the tolls are now being collected on the wrong side of the bridge. They should, he argued, be collected coming from the San Francisco side, where the few lanes of the bridge open up to many lanes. This would reduce or eliminate congestion. .

He listed other suggestions that showed his firm and creative grasp of the useful idea. Putting the third stop light on vehicles (which was finally put into effect in 1985). Numbering interchanges. Installing flashing red and yellow lights at different rates. (He explained that his wife’s grandfather was color blind and drove through a flashing red light when she was with him.) Getting vehicle owners to have reflective white strips on the front bumpers of their cars, helping police spot stolen vehicles. Some of his suggestions are still percolating deep in the bureaucracies and may yet go into effect.

Charlie never got the hang of the internet but he covered more territory and reached more people in his personal face-to-face way than anybody ever did on the internet.

Charlie was born on a homestead farm eight miles from Weldona, Colorado. He attended a one-room school house and then moved on to a middle and high school in Ft. Morgan, Colorado. He got “ink in his blood,” as he liked to say, by working on the school paper called the Megaphone and then as a printer’s devil at the weekly Morgan Herald.

He was drafted into the army in l943 and served as an infantryman with the 343rd regiment, 86th Infantry Division. He was severely sounded in 1945 in the Ruhr Pocket battle near Cologne, Germany, the last major battle of the war. He suffered leg and hip injuries and had a l6 inch gouge out of his right hip that cut within a quarter inch of the bone. He spent six months in the hospital. He was recommended for sergeant but he refused the promotion and ended the war as a private first class.

After his recovery, Charlie came to the Bay Area and took his undergraduate work at Napa Community College and San Francisco State, then did graduate work in sociology at the University of Washington, and in city and regional planning at the University of California-Berkeley.

In 1949, Charlie joined the American Friends Service Committee and became a lifelong volunteer, working on a host of projects. He did everything from helping with a clothing drive in Napa to being part of the crew that built the original Neighborhood House in Richmond.

Charlie met Anne Read in l954, a college student in Oregon, when she was on an AFSC summer project in Berkeley. Charlie visited the project, spotted Anne, and double dated with her. When she returned to Oregon State for her senior year, Charlie wrote her every single day. The two were married the following summer in June of l955.

Charlie is survived by Anne, two sons Greg and Jay, daughter-in-laws Karen Vartarian and Andrea Paulos, and granddaughter Mabel.

The family asks that, in lieu of flowers, please send a donation in Charlie’s name to the American Friends Service Committee, 65 9th St., San Francisco, Calif. 94l03.

I asked Anne why Charlie, the inveterate communicator, had not taken to the internet. Charlie, she replied, was a print guy and simply could not understand the internet. “He never ever used email,” she said. “He still thought he had to go to a library to make up a bibliography. I think Charlie was so sure that making a bibliography meant a lot of hard work, he couldn’t possibly do it on the internet.”

Well, Charlie, you may have missed the internet but you covered more territory and reached more people in your direct personal way with good ideas than anybody ever did on the internet.

Here are some of Charlie’s favorite pamphlets:

Governor Pat Brown’s Work Improvement Program

Pamphleteering: An Old Tradition

Short Statement on Plamphleteering