arts@sfbg.com

TRASH “Obsessed” is a term not infrequently bandied about when talking about film directors, particularly those with particular, distinctive thematic or stylistic trademarks that are clearly more a matter of personal than commercial instinct. It applies well enough to now 82-year-old Spaniard Jess Franco, who’s been making movies for 55 years — he’d already clocked time as a philosophy student, earned a law degree, written pulp novels, and flirted with becoming a jazz musician before turning to the medium — and doubtless won’t stop till he keels over dead with a Red One in his hand.

But in his case, the more relevant term might be “addicted.” What can you say about a man who’s made a number of features probably unknowable to himself, let alone anyone else (let’s just say somewhere not far below 200), often working under dozens of pseudonyms? Their funding cobbled together from umpteen international sources (not excluding Liechtenstein), distributed under hundreds of titles and in myriad edits for specific markets (i.e. more sex where allowed, more violence where not)? You can’t say he’s in it for the money, since chronic lack of it has helped shape his aesthetic, not to mention the composition of loyal colleagues willing to work now and get paid (maybe) later.

You can say he’s an admitted voyeur whose peephole is the camera, and that this particular addiction must be satisfied no matter what the obstacles, or how sub par the results. Hence, who knows how many hours of frequently lurid, strange, usually shoestring filmmaking that would probably drive any wannabe completist mad, particularly since so much of it shows every boring and/or depressing sign of having been thrown together just because it could be. Yet the House of Franco provokes wary fascination — like the contents of a hoarder’s home, it may seem a reeking pile of junk at first glance, but with gas mask and gloves on you will eventually uncover interesting artifacts of a unique life lived deep in the nether-realms of Eurotrash genre cinema.

Several vintage Francos have come out on Blu-ray and DVD lately, offering movies that, depending on your tolerance, will fall into the “good to know” or “too much information” category. If you’re a newbie, it’s best to start with the 1960s hits that briefly made him look like a global contender. He struck pay dirt with 1961’s The Awful Dr. Orloff, Spain’s first horror movie and a pretty shocking one to have gotten away with during the censorious Francisco Franco regime. He was always pushing the envelope further than the censors liked, particularly with such sexy surrealisms later in the decade as Succubus (1967), Venus in Furs (1969), and Marquis de Sade’s Justine (1968). Dreamlike in imagery and narrative, their arty psychedelic kitsch still casts a certain spell.

For good or ill, they also typed Franco as a man who could work in any language (he speaks a half-dozen), anywhere, with any cranky B-level international star (Klaus Kinski, Christopher Lee, etc.) imported for marquee value, and make something exploitable out of any slim means. Thus the means steadily got slimmer — though he’d still get an occasional bump in production values on titles like 1975’s Jack the Ripper (a curiously flat enterprise despite the genius casting of Kinski), 1980 slasher Bloody Moon, and 1988 gorefest Faceless. Who knows where his career might have gone if he’d held out for better projects? Probably he wouldn’t have increasingly crossed over from softcore to porn, let alone made 15 features in one not-so-exceptional year (1983).

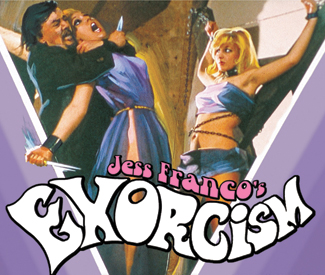

But then, neither would he likely have made numerous movies that seem driven by insatiability alone — like 1972’s Sinner (a.k.a. Diary of a Nymphomaniac, a surprisingly moralistic corruption-of-youth tale; 1973’s Countess Perverse, succinctly described on IMBD as “Two wealthy aristocrats lure a virginal girl to a Spanish island for a night of sex, death, and cannibalism;” 1973’s Female Vampire, the first starring vehicle for waifish, exhibitionist muse Lina Romay, his spouse and collaborator until her death earlier this year; and 1974’s Exorcism, with the short, squat director himself as a murderously crazy ex-priest who mistakes swingers’ mock “black masses” for the real thing. These four were recently issued for home viewing. The latter two (on Kino Lorber) come complete with alternate versions emphasizing bloody mayhem over naked frisking.

They are, of course, a mixed bag, sometimes winningly eccentric or even poetical, sometimes just sleazy and dull. For every decent to genuinely good Franco opus (among the latter, improbably, 1976’s quite serious Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun), a dozen or more are likely better off unseen when they’re not outright unseeable. (He’s left behind many films unfinished, lost or in legal limbo). What are we missing in the likes of 1980’s Two Female Spies With Flowered Panties, 1981’s Bloodsucking Nazi Zombies, 1984’s The Night Has a Thousand Sexes, 1986’s Lulu’s Talking Ass, 1986’s Tribulations of a Cross-Eyed Buddha, or this year’s Al Pereira vs. the Alligator Women? Maybe they’re best kept suspended somewhere between Franco’s imagination and our own.