cheryl@sfbg.com

SFIFF Most contemporary Americans don’t know much about Uganda — that is, beyond Forest Whitaker’s Oscar-winning performance as Idi Amin in 2006’s The Last King of Scotland. Though that film took some liberties with the truth, it did effectively convey the grotesque terrors of the dictator’s 1970s reign. (Those with deeper curiosities should check out Barbet Schroeder’s 1974 documentary General Idi Amin Dada: A Self Portrait.) But even decades post-Amin, the East African nation has somehow retained its horrific human-rights record. For example: what extremist force was behind the country’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill, which proposed the death penalty as punishment for gayness?

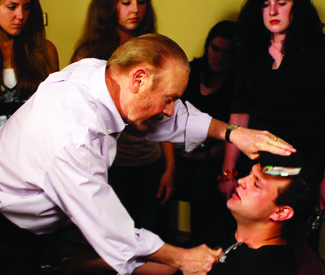

The answer might surprise you, or not. As the gripping, fury-fomenting doc God Loves Uganda reveals, America’s own Christian Right has been exporting hate under the guise of missionary work for some time. Taking advantage of Uganda’s social fragility — by building schools and medical clinics, passing out food, etc. — evangelical mega churches, particularly the Kansas City, Mo.-based, breakfast-invoking International House of Prayer, have converted large swaths of the population to their ultra-conservative beliefs.

Filmmaker Roger Ross Williams, an Oscar winner for 2010 short Music by Prudence, follows naive “prayer warriors” as they journey to Uganda for the first time; his apparent all-access relationship with the group shows that they aren’t outwardly evil people — but neither do they comprehend the very real consequences of their actions. His other sources, including two Ugandan clergymen who’ve seen their country change for the worse and an LGBT activist who lives every day in peril, offer a more harrowing perspective. Evocative and disturbing, God Loves Uganda seems likely to earn Williams more Oscar attention.

>>Check out our short reviews of several SFIFF films of interest.

More outrage awaits in Fatal Assistance, Port-au-Prince native Raoul Peck’s searing investigation into the bungling of post-earthquake humanitarian efforts in Haiti. So many good intentions, so many dollars donated, so many token celebrities (Bill Clinton, Sean Penn) involved — and yet millions of Haitians remain homeless, living in “temporary” shelters. Disorganization among the overabundance of well-meaning NGOs that rushed to help is one cause; there’s also the matter of nobody trusting the Haitian government to make its own financial decisions. Peck, a former Minister of Culture, offers a rare insider’s perspective. Though the film’s voice-overs (framed as letters that begin “dear friend”) can get a little treacly, the raw evidence Peck collects of “the disaster of the community not being able to respond to the disaster” is powerful stuff.

There’s more levity sprinkled amid the tragedy (and bureaucratic frustration) contained in Ilian Metev’s Sofia’s Last Ambulance. If nothing else, this doc will make you extremely cautious if you ever find yourself visiting the capital of Bulgaria; its depiction of the city’s medical care is grim at best. An underpaid, harried trio — doctor, nurse, and driver — grapple with dispatchers who don’t pick up and drivers who don’t let ambulances pass, bad directions, outdated equipment, and other unbelievable situations that would be funny if lives weren’t hanging in the balance. Metev never films the patients, instead keeping his focus on the paramedics. Sarcastic nurse Mila Mikhailova is a standout, sweetly calming down an injured child, bluntly advising a drug addict, and joking about her love life with her co-workers. Only during rare moments of downtime does her exhaustion emerge.

>>Dennis Harvey on SFIFF’s Finnish angle.

More lives in chaos — albeit slightly more existentially — are depicted in A River Changes Course, which picked up a Grand Jury Prize for World Cinema Documentary at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival. Cambodian American filmmaker Kalyanee Mam followed a trio of rural Cambodian families over several years, eventually crafting a vividly-shot, meditative look at lives being forced to modernize. Talk about frustrating: farmers grapple with a new worry — debt — so the eldest daughter heads to Phnom Penh to work in a factory. But the paltry wages she earns aren’t enough to offset the money they will have to spend on food, since they can’t farm enough to eat without her around to help. Elsewhere, a teenage boy who figured he’d grow up to be a fisherman takes a backbreaking planting job when the fish grow scarce; he confesses to Mam that he’s long since given up any dreams of getting an education. “Progress” has rarely felt so bleak.

Adding a much-needed dose of quirk to all of the above is Kaspar Astrup Schröder’s Rent a Family Inc., about Ryuichi, a Tokyo man whose business name translates to “I want to cheer you up.” He’s a professional stand-in, offering himself or any of his rotating cast of staffers to pretend to be friends or relatives in situations, including weddings, where the real thing is either not available or won’t suffice.

That premise alone would make for an intriguing doc — though there’s a disclaimer that certain scenes with clients are “reconstructed” — but Ryuichi’s career choice feels even more surreal once it’s revealed how dysfunctional his own family is; among a wife and two kids, he gets along best with the family Chihuahua. Though Schröder focuses on Ryuichi’s ennui at the expense of delving into, say, what it is about Japanese culture that enables the need for fake family members, the guy is undeniably fascinating. “I’m like a handyman, fixing people’s social engagements,” he explains — but he has no clue how to mend his own. *

SAN FRANCISCO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL

April 25-May 9, most shows $10-15

Various venues

festival.sffs.org