GOLDIES “Anybody want more popcorn? How about coffee?”

Ryan T. Smith is calling out to a packed audience in the oddest-shaped dance studio in San Francisco — long and narrow, like a bowling alley. The occasion is the latest installment in RAWdance’s popular bi-annual CONCEPT series, started in 2007 by Smith and partner Wendy Rein in their Duboce Triangle neighborhood.

CONCEPT is an occasion where dance watching and socializing go hand in hand. You pay what you can … and you pitch in with moving the furniture. An old-fashioned salon of serious fun but also serious art, the series has become one of the most congenial places to watch dance in SF.

And yet the project started as something like a self-help group. When Smith and Rein moved to the city, they came into an environment rich in dance theater, multimedia, text-based dance, and identity- and gender-inspired material. “This is not who we are,” Rein explains while sitting at their kitchen table. “Our dances are abstract.” And, continues Smith, “We also didn’t know anybody [at the time].”

Looking around, however, they found artists who — like themselves — had pieces that had been seen only once, or were works in progress. Artists who wanted to rework something, or just try out new material. Today, over 60 choreographers have shown at CONCEPT; anyone can apply, though the team curates the show lightly to ensure a good mix.

Another reason behind CONCEPT arises from the duo’s desire to make dance more generally accessible. “We are so tired of going to dance concerts and seeing the same people all the time,” they agree. Rein remembered a couple who just walked into CONCEPT off the street. “I just loved that.”

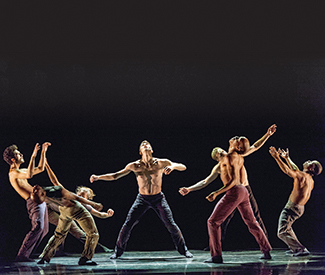

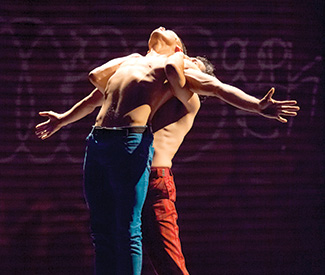

Guardian photo by Saul Bromberger and Sandra Hoover

They don’t complain about the lack of attention paid to theatrically demanding dance. They don’t wait for audiences — they go to them. Locally, they have performed in public spaces like Union Square and beneath the SF City Hall Rotunda.

The duo calls its choreography “abstract;” in truth, that’s something of a misnomer since there is no such thing as abstract dance. When you put a human being on a stage, abstraction goes out the back door. RAWdance derives its strength from the fact that the pieces tell stories without relying on explicit narratives. “We don’t spoon-feed our audiences. We just want to go so deep that the experience becomes visceral,” they agree.

For Two by Two: Love on Loop, they created a 20-minute dance on themselves, and then taught it to 12 very different couples who performed it over an eight-hour period in the middle of the UN Plaza. For A Public Affair, a 10-minute duet performed at the height of the dinner hour at the now closed Orson Restaurant, they condensed gestures and movements that would have looked familiar to the patrons. The Beauty Project, first performed in an empty storefront, eventually made it into a theater — but its inspirations (mannequins, a fashion-show runway) remained unmistakable.

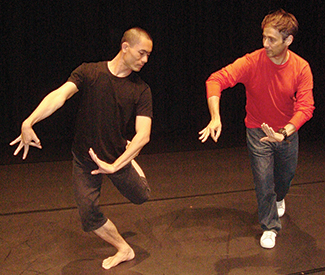

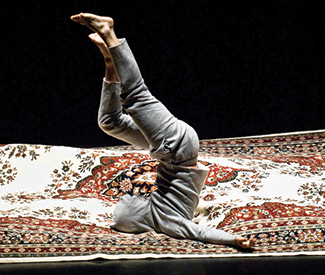

In their own duets — still their preferred way of working — Smith and Rein often move like liquid sculptures; we see them as one even as they strive to pull apart. They were at first drawn to each other in college because choreographers so frequently paired them together. It makes sense.

Both of them are tall and long-limbed, with superb techniques. Rein looks fragile but she is fierce. “I feel more comfortably working with Wendy, trying out things that are physically bizarre, than with anybody else in a studio,” Smith says. “I trust her with my weight.”

Rein feels the same way but explains the trust also comes from the fact that “we create everything together, so we are interested in seeing the interactions between us.” Chatting with them in their kitchen, you get the sense that they are completely in tune with each other. They finish each other’s sentences like an old married couple (which they are not).

At the most recent CONCEPT series last August, RAWdance showed the beginnings of new piece, Turing’s Appel, inspired by Alan Turing, the pioneering British scientist who was driven to suicide because of his homosexuality. (The piece is set to premiere this summer at Z Space.) Dance critic Heather Desaulniers described the excerpt in terms of the questions she saw the choreographers raising: “How do constraints affect physicality; how do situations differ when change is purposeful or accidental; what circumstances make the most sense in the body?”