steve@sfbg.com; molly@sfbg.com

San Francisco’s streets and public spaces are undergoing a drastic transformation — and it’s happening subtly, often below the radar of traditional planning processes. Much of it was triggered by the renegade actions of a few outlaw urbanists, designers, and artists.

But increasingly, their tactics and spirit are being adopted inside City Hall, and the result is starting to look like a real urban design revolution — one that harks back to a movement that was interrupted back in the 1970s.

One of the earliest signs of the new approach emerged in 2005 on the first Park(ing) Day, the brainchild of the hip, young founders of the urban design group Rebar. The idea was simple: turn selected street parking spots around San Francisco into little one-day parks. Just plug some coins in the meter to rent the space, then set up chairs or lay down some sod, and kick it.

It was a simple yet powerful statement about how San Franciscans choose to use public space — and the folks at Rebar expected to get in trouble.

“When we did the first Park(ing) Day in 2005, JB [a.k.a. John Bela] and I were just prepared to be arrested and hauled into court,” Rebar’s Matthew Passmore told us at a recent interview in the group’s new Mission District warehouse space. “But nothing like that happened.”

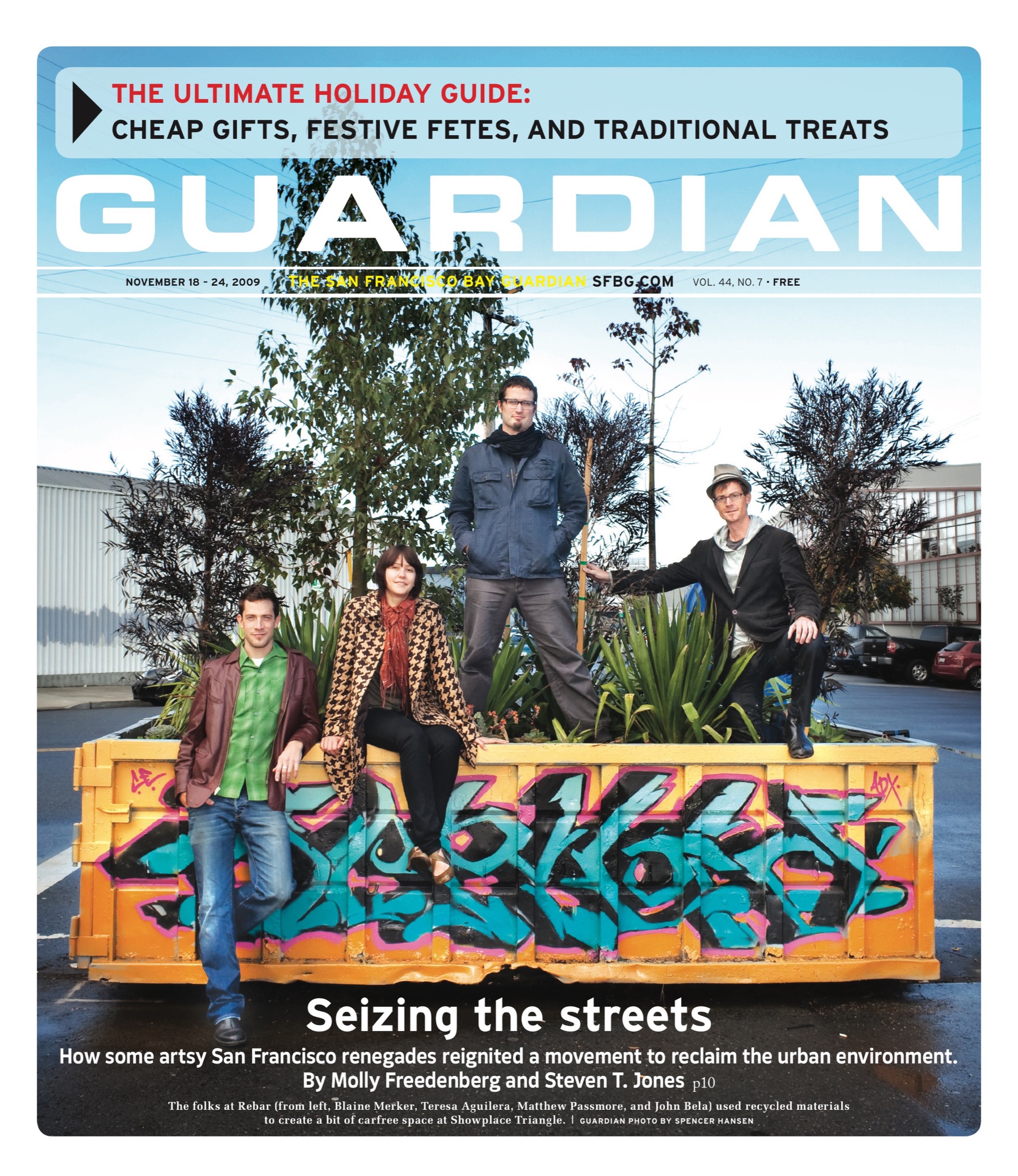

Instead, City Hall called.  Rebar’s Blaine Merker, Teresa Aguilera, Matthew Passmore, and John Bela at their carfreee space at Showplace Triangle

Rebar’s Blaine Merker, Teresa Aguilera, Matthew Passmore, and John Bela at their carfreee space at Showplace Triangle

“We got a call from the director of city greening, who said this is great, I want to meet with you guys and talk about how the city can support this kind of activity,” Passmore said. “Much to our surprise, the city was totally responsive as opposed to shutting us down and imprisoning us.”

Bela said the group discovered that Mayor Gavin Newsom’s administration was looking for just the sort of innovative, cool, environmental ideas that were Rebar’s focus. And that connection merged with other people’s efforts — like sidewalk-to-garden conversions being pioneered by Jane Martin, the urban gardening and bicycling movements, and the unique public art that was making its way back from Burning Man. That created a catalyst for a wide array of city initiatives, from the Sunday Streets road closures to temporary art installations that began popping up around the city to the Pavement to Parks program that creates short-term parks in underutilized roadways.

“It was a single interaction five years ago, and now we have things like Sunday Streets,” Bela told us on Sept. 18’s Park(ing) Day, in which various individuals and groups took over more than 50 parking spots around town. “It’s about reclaiming the streets for people.”

Park(ing) Day itself blew up, becoming a worldwide phenomenon that is now in 151 cities on six continents, and one that the Mayor’s Office is planning to turn into a more permanent plan, with the regular conversion of some parking spots on commercial corridors into outdoor seating areas.

“You had a few guys and a girl who had an idea and now it’s an international event,” Mike Farrah, a longtime Newsom lieutenant who now heads the Office of Neighborhood Services and has been the main contact in City Hall for Rebar and similar groups, told the Guardian.

Locally, the success of events like Park(ing) Day have changed San Francisco’s approach to urban spaces, particularly on land left dormant by the economic downturn. Rebar, the permaculture collective Upcycle, and former MyFarm manager Chris Burley plan to turn the old Hayes Valley freeway property near Octavia, between Oak and Fell streets, into a massive community garden and gathering space. Plans are being hatched for temporary uses on Rincon Hill properties approved for residential towers. “Green pod” seating areas are sprouting along Market Street and there are plans to extend the Sunday Streets road closures next year. And, perhaps most amazingly, most projects are being accomplished with very little funding.

How has San Francisco suddenly shifted into high gear when it comes to creating innovative new public spaces? The key is their common denominator: they’re all temporary. As such, they don’t require detailed studies, cumbersome approval processes, or the extensive outreach and input that can dampen the creative spark.

But San Francisco is starting to prove that dozens of short-term fixes can add up to a true transformation of the urban environment and the citizenry’s sense of possibility.

EVOLUTION OF THE PRANK

Rebar began as a group of friends and artists who came together to enter a design contest in 2004. Passmore was a practicing lawyer and Bela was a landscape architecture student at UC Berkeley. They chose the name Rebar for future collaborations, the first of which was Park(ing) Day.

Passmore, who had a background in conceptual art before going to law school, discovered a legal loophole that might allow for anything from a burlesque performance to a temporary swimming pool to be installed in metered parking spaces. Bela recruited Blaine Merker, a fellow landscape architecture student with whom he’d won a design competition, to join the effort.

Park(ing) Day was a hit, getting great press and igniting people’s imaginations. “We realized after we did it, like, oh, people are really getting this,” Merker said. And Rebar was off. In the following years they added a fourth principal, graphic designer Teresa Aguilera, and took on a number of acclaimed projects: planting the Victory Garden in Civic Center Plaza, building the Panhandle Bandshell from old car hoods and other recycled parts, creating COMMONspace events (from “Counterveillance” to the “Nappening”) in privately-owned public spaces, and designing the Bushwaffle (commissioned for the Experimenta-Design biennale in Amsterdam) to help soften paved urban spaces and create a sense of play.

Through it all, the group maintained its prankster spirit. When they were invited to present the Bandshell project at the prestigious Venice Biennale festival, Rebar members showed up costumed as Italian table-tennis players (a joke that mostly baffled other attendees, they said).

They told us every project needed to have a “quotient of ridiculum.” Or as Bela put it, “That’s how we know project has evolved to the right point — when we’re on the floor laughing.”

As Rebar found success, it was still mostly a side project for members who had other full-time jobs. “We were all playing hooky all the time,” said Merker, who, like Bela, joined a landscape architecture firm after he finished school. “It just got worse and worse.”

So now, they’re trying to turn their passion into a profession, recently moving into a cool warehouse office and workspace in the Mission. “We’re shifting our practice a little to have the same sort of spirit but trying to figure out how we can make that an occupation,” Merker said.

It’s also about moving from those short-lived installations to something a little more lasting, even while working within the realm of temporary projects. As Aguilera said, “A lot of the projects we started with were creating moments to maybe think about. But we’re shifting into more permanent ways to interact with the city.”

They may not be sure where they’re headed as an organization, but they have a clear conception of their canvas, as well as the traditions they draw from (including movements like the Situationists and artists such as Gordon Matta-Clark, who worked in urban niche spaces) and the fact that they are part of an emerging international movement to reclaim and redesign urban spaces.

“We’re not the originators of any of this stuff,” Bela said. “It’s like emerging phenomena happening in cities all over the world. We just happened to have plugged into it early on and we continue to push it.”

EXPANDING THE POSSIBLE

Rebar is strongly pushing a reclamation of spaces that have been rather thoughtlessly ceded to the automobile over the last few decades. “Street right-of-way is 25 percent of the city’s land area. A quarter of the city is streets,” Bela said. “And those streets were designed at the time when we wanted to privilege the automobile.

“So basically, there’s all this underutilized roadway,” he continued. “It’s asphalt and it’s pavement, and the city wants to reclaim some of those spaces for people. That’s a thread we’ve been exploring in our work for a long time, and now it’s elevated up to a citywide planning objective.”

The short-term nature of the projects comes in part from political necessity: temporary projects are usually exempt from costly, time-consuming environmental impact reports. Demonstration projects also don’t need the extensive public input that permanent changes do in San Francisco. But there’s more to the philosophy.

“It stands on this proposition that temporary or interim use does actually improve the character of the city,” Passmore said. “People used to think that if something is temporary or ephemeral, what good is it? It’s just here today, gone tomorrow. But I think now people are realizing that the city can be improved like this.”

And it goes even deeper than that. When people see parking spaces turned into parks, vacant lots blossoming with art and conversation nooks, or old freeway ramps turned into community gardens, their sense of what’s possible in San Francisco expands.

“What we’re remodeling is people’s mental hardware. It’s like stretching. You have to bend something a little more than it wants to go, and the next time you do that, it’s that much easier,” Merker said.

“There’s also a psychological aspect to that. When people see a crack in the Matrix open up, if you will, it can open up a whole lot more than just that one moment,” he said.

For those who have been working on urbanism issues in San Francisco for a long time, like Livable City director Tom Radulovich, this new energy and the tactic of conditioning people with temporary projects is a welcome development. “There is a huge resistance to change in San Francisco, no matter what the change is, and a lot of that stems from fear,” Radulovich said. But with temporary projects, he said, “you can establish what success looks like from the outset.”

BUILDING ALLIANCES

The Rebar folks have been fairly savvy in their approach, making key friends inside City Hall, people who have helped them bridge the gap between their idealism and what’s possible in San Francisco.

“We are a process-driven city, and temporary allows you to create change without fear,” Farrah told us. He said the partnership between the Mayor’s Office and community groups that want to do cool, temporary public art really began in the summer of 2005 with the Temple at Hayes Green by longtime Burning Man temple builder, David Best.

Farrah had connections to the Burning Man community, so he facilitated the placement of the temple along Octavia Boulevard, then one of the city’s newest and least developed public spaces. Next came the placement of another Burning Man sculpture, Flock by Michael Christian, in Civic Center Plaza that fall. Both projects got funding and support from the Black Rock Arts Foundation, a public art outgrowth of Burning Man.

“I saw, after some of the temporary art and special events, how it’s changed people’s ideas about what’s possible,” Farrah said. “There has been a change in the way people view the streets.”

That got Farrah thinking about what else could be done, so he approached BRAF’s then-director Leslie Pritchett and Rebar’s Bela, telling them, “I need you to look at San Francisco like a canvas. Tell me the things you want to do, and I’ll tell you if it’s possible or not. And that’s led to a lot of cool stuff.”

Livable city advocates like Radulovich — progressives who are generally not allied with Newsom and who have battled with him on issues from limiting parking to the Healthy Saturdays effort to create more carfree space in Golden Gate Park — give the Mayor’s Office credit for its greening initiatives.

He credits Greening Director Astrid Haryati and DPW chief Ed Reiskin with facilitating this return to urbanism. “He’s really responsive and he gets it,” Radulovich said of Reiskin. “This is really where a lot of energy is going in the mayor’s office. It seems to have captured their imaginations.”

Another catalyst was last year’s visit by New York City transportation commissioner and public space visionary Janette Sadik-Khan, who met with Reiskin and Newsom on a trip sponsored by Livable City and the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition. Radulovich said her message, which SF has embraced, is that, “There are low-cost, reversible ways you can reclaim urban space in the near term.”

The Mayor’s Office, SFBC, and Livable City partnered last year to create Sunday Streets, which involved closing streets to cars for part of the day. The events have proven hugely successful after overcoming initial opposition from merchants who now embrace it.

Then there’s the Pavement to Parks program — which involves converting streets into temporary parks for weeks or months at a time — that grew directly from the Sadik-Khan visit. Andres Power, who directs the program for the Planning Department, told us the visit was a catalyst for Pavement to Parks: “She came to the city a year ago and inspired my director, Ed Reiskin.”

“We’re rethinking what the streets are and what they can be,” Power said. “It’s rewarding to see this stuff happen and to be at the forefront of a national effort to imagine what our streets could be.”

DE-PAVE THE CONCRETE

Pavement to Parks launched last year, a multiagency effort with virtually no budget, but the mandate to use existing materials the city has on hand to turn underutilized streets into active parks. “It looks at areas where we can reclaim space that’s been given over to cars over the decades,” Power told the Guardian.

At the first site, where 17th Street meets Market and Castro, the city and volunteer groups used planters and chairs to convert a one-block stretch of street that was little-used by cars because of the Muni line at the site.

“We bent over backward to make the space look temporary,” Power said, noting the concern over community backlash that never really materialized, leading to two time extensions for the project. “But we’re now ready to revamp that whole space.”

Another Pavement to Parks site at Guerrero and San Jose streets was created by Jane Martin, whom Newsom appointed to the city’s Commission on the Environment in part because of the innovative work she has done in creating and facilitating sidewalk gardens since 2003.

As a professional architect, Martin was used to dealing with city permits. But her experience in obtaining a “minor sidewalk encroachment permit” to convert part of the wide sidewalk near a building she owned on Shotwell Street into a garden convinced her there was room for improvement.

“At that point, I was really jazzed with the result and response [to her garden] and I wanted to make it so we could see more of it,” she said. So she started a nonprofit group called PlantSF, which stands for Permeable Lands As Neighborhood Treasure. Martin worked with city agencies to create a simpler and cheaper process for citizens to obtain permits and help ripping up sidewalks and planting gardens.

“We want to de-pave as much excess concrete as possible and do it to maximize the capture of rainwater,” she said.

Martin said the models she’s creating allow people to do the projects themselves or in small groups, encouraging the city’s DIY tradition and empowering people to make their neighborhoods more livable. More than 500 people have responded, creating gardens on former sidewalks around the city.

“We’ll get farther faster with that model,” she said. “It’s really about engaging people in their neighborhoods and helping them personalize public spaces.”

San Francisco has always been a process-driven city. “We in San Francisco tend to plan and design things to death, so as a result, everything takes a very long time,” Power said.

But with temporary projects under Pavement to Parks, the city can finally be more nimble and flexible. Three projects have been completed so far, and the goal is to have up to a dozen done by summer.

“We’re working feverishly to get the rest of the projects going,” Power said.

One of those projects involves an impending announcement of what Power called “flexible use of the parking lane” in commercial corridors like Columbus Avenue in North Beach. “We’re taking Park(ing) Day to the next level.”

The idea is to place platforms over one or two parking spots for restaurants to use as curbside seating, miniparks, or bicycle parking. “The Mayor’s Office will be announcing in the next few weeks a list of locations,” Power said. “There have been locations that have come to us asking for this.”

“The idea is to do a few of these as a pilot to determine what works and what doesn’t. The goal is to use their trial implementation to develop a permanent process,” Power said. “We want to think of our street space as more than a place for cars to drive through or park.”

Rebar was responsible for the last of the completed Pavement to Parks projects. Known as Showplace Triangle, it’s located at the corner of 16th and Eighth streets in the Showplace Square neighborhood near Potrero Hill. For Rebar, it was like coming full circle.

“We started doing this stuff about five years ago, finding these niches and loopholes and exploring interim use as a strategy for activating urban space,” Bela said. “And to our surprise, what we perceived as a tactical action is now being embodied by strategic players like the Planning Department.”

REUSE, RECYCLE, REINVENT

The Rebar crew was like kids in a candy store picking through the DPW yard.

“These projects are all built with material the city owns already, so we had the opportunity to go down to the DPW yard and inventory all of these materials they had, and figure out ways to configure them to make a successful street plaza,” Bela said.

So they turned old ceramic sewer pipes into tall street barriers topped by planter boxes, and built lower gardens bordered by old granite curbs.

“We are trying to be as creative as possible with the use of materials the city already has on hand,” Power said. In addition to the DPW yard that Rebar tapped for Showplace Triangle, Power said the Public Utilities Commission, Port of SF, and the Recreation and Parks Department all have yards around the city that are filled with materials.

“They each have stockpiles of unused stuff that has accumulated over the years,” he said.

For her Pavement to Parks project on Guerrero, Martin used fallen trees that originally had been planted in Golden Gate Park — pines, cypress, eucalyptus — but were headed for the mulcher. Not only were they great for creating a sense of place, they offered a nod to the city’s natural history.

But perhaps the coolest material that had been sitting around for decades was the massive black granite blocks that Rebar incorporated into Showplace Triangle. “One of the most interesting materials that we used in Showplace Triangle was the big granite blocks from Market Street that were taken off because merchants didn’t like people encamping there. They were too successful as spaces, so they got torn out,” Merker said.

Bela said they couldn’t believe their eyes: “We saw these stacks of five-by-five by one-foot deep black granite. Just extraordinary. If we were to do a public project today, we could never afford that stuff. There’s no way. But the taxpayers bought that stuff back in the ’70s and now it’s just sitting there in the DPW yard. It’s a crime that it’s not being used, so it was great to get it back out on the street.”

Radulovich said the return of the black granite boxes to the streets represents the city coming full circle. He remembers talking to DPW manager Mohammad Nuru as he was removing the last of them from Market Street in the 1970s, citing concerns about people loitering on them.

“To see them put up again in JB’s project was symbolic of where the city went and where it’s coming back from,” Radulovich said. “It’s almost like the livability revolution got interrupted and we lost two decades and now it’s picking up again.”

Back in the 1970s, Radulovich said the city was actively creating new public spaces such as Duboce Triangle. It was also creating seating along Market Street and generally valuing the creation of gathering places. But in the antitax era that followed, public sector maintenance of the spaces lagged and they were discovered by the ever-growing ranks of the homeless that were turned loose from institutions.

“The fear factor took over,” Radulovich said. “We did a lot to destroy public spaces in the ’80s and ’90s.”

But by creating temporary public spaces, people are starting to realize what’s been lost and to value it again. “These baby steps are helping us relearn what makes a good public space,” Radulovich said.

For much of the younger generation, building public squares is a new thing. As Aguilera noted, “We don’t have a lot of public plazas anymore or places for people to gather. When Obama was elected, where did everyone go in the city? Into the streets. So we’re trying to give that back to the city.”

CARS TO GARDENS

Perhaps the most high-profile laboratory for these ideas is the Hayes Valley Farm, a temporary project planned for the 2.5 acres of freeway left behind after the Loma Prieta earthquake. The publicly-owned land between Oak and Fell streets is slated for housing projects that have been stalled by the slow economy.

“The site’s been vacant for 10 years. They came up with a beautiful master plan. And the moment they’re ready to move on the master plan, there’s an economic collapse, so nothing is happening,” Bela said.

In the meantime, the Mayor’s Office and Hayes Valley Neighborhood Association pushed for temporary use of the neglected site. They approached the urban farming collectives MyFarm and Upcycle. Later, Rebar was brought in to design and coordinate the project.

Now the group known as the Hayes Valley Farm Team has an ambitious plan for the area: part urban garden, part social gathering spot, and part educational space. There will be an orchard of fruit trees, a portable greenhouse, demonstrations on urban farming, and a regular farmers market.

“The different topography of ramps allows for different growing conditions. These ramps are prime exposure to the south,” Merker said. “They create these areas that can produce some really great growing conditions, so it’s kind of funny that this freeway is responsible for that. The ramps actually create different microclimates.”

Most remarkably, the whole project is temporary, designed to be moved in three years. “We’re interested in developing infrastructure and tools and machinery and implements that are sort of coded for the scale of the city: a lot of pedal-powered things, a lot of mobile infrastructure, and smaller things that are designed to be useful in a plot that is only 2.5 acres,” Bela said. “Then when we need to move on, we’ll be able to do that. It’s about being strategic with some of the investments so we can take some of the tools we develop here and move it to the next vacant lot down the street.”

The project has lofty goals, ranging from creating a social plaza in Hayes Valley to educating the public about productive landscaping. “We’re getting away from ideas of turning parks into food production — it can be both,” said David Cody of Upcycle. “We want to just crack the awareness that cities can be multi-use and agriculture doesn’t mean farm.”

This is perhaps the most ambitious temporary project the Mayor’s Office has taken on. “Rebar pushed the envelope on what is possible. I told them it would be a tough one,” Farrah said of the project. But he loves the concept: “You can argue that putting gardens in temporary spaces changes attitudes.”

Symbolically, this land seems the perfect place for such an experiment. “This really is a special spot. If you look at a map of the city, Hayes Valley is in the very center, and this is right in the heart of Hayes Valley,” Aguilera said. “And right now, in the heart of a neighborhood in the heart of the city, there’s this vacant, fallow reminder of what used to be there. We’re looking to turn it into a new beating heart that brings together lots of different parts of the community.”

ACTIVATING DORMANT SPACES

Activating dormant spaces in the city isn’t easy, particularly for properties with pending projects. In Hayes Valley, for example, the Rebar crew was required to develop a detailed takedown plan.

“A lot of development is hesitant to get involved with these interim uses because at the end, they’re worried that it’s going to be framed as the evil, money-hungry developer coming in to kick out artists or farmers,” Passmore said. “But the reality is, they are very generously opening up their space is the first place.”

With last year’s crash of the rental estate and credit markets, development in San Francisco stalled, leaving potentially productive land all over the city. “As the city has gone through an economic downturn, like now, the city has a lot of vacant lots with developer entitlements on them, but nothing is being built right now. Those are spaces the public has an interest in,” Merker said, citing Rincon Hill as a key example.

Michael Yarne, who facilitates development projects for the Mayor’s Office of Economic Development, has been working on how developers might be encouraged to adopt temporary uses of their vacant lots.

“How can we credit them to do a greening project on a vacant lot?” Yarne asks, a problem that is exacerbated by the complication that neither the developers nor local government have money to fund the interim improvements.

He looked at the possibility of using developer impact fees on short-term projects, but there are legal problems with that approach. The courts have placed strict limits on how impact fees are charged and used, requiring detailed studies proving that the fees offset a project’s real cost and damage.

“But there is other value we can give as a city without spending a dollar — and that is certainty,” said Yarne, a former developer. He said developers value certainty more than anything else.

Right now, developers have to return to the Planning Commission every year or so to renew project entitlements, something that costs time and money and potentially places the project at risk. But he said the city might be able to enter into developer agreements with a project proponent, waiving the renewal requirement for a certain number of years in exchange for facilitating short-term projects.

“Everyone wins. We get a short-term use, and the developer gets certainty that they won’t lose their rights,” Yarne said, noting that he’s now developing a pilot project on Rincon Hill. “If that works, that could be a template we could use over and over.”

Radulovich is happy to see the new energy Rebar and other groups are infusing into a quest to remake city streets and lots, and with the use of temporary projects to expand the realm of the possible in people’s minds: “Let’s get people reimagining what the streets could be.”

www.rebargroup.org

Rebar’s Blaine Merker, Teresa Aguilera, Matthew Passmore, and John Bela at their carfreee space at Showplace Triangle

Rebar’s Blaine Merker, Teresa Aguilera, Matthew Passmore, and John Bela at their carfreee space at Showplace Triangle